The American Visionary Art Museum in Baltimore, Md., was founded in 1995 and contains 67,000 square feet of exhibition space. The museum specializes in “outsider” art and its permanent collection is 4,000 pieces strong. CNN proclaimed the museum “One of the most fantastic museums anywhere in America.”

The museum defines outsider art in its mission statement as:

“Visionary art as defined for the purposes of the American Visionary Art Museum refers to art produced by self-taught individuals, usually without formal training, whose works arise from an innate personal vision that revels foremost in the creative act itself.”

Some highlights of the collection include kinetic sculptures from the annual Kinetic Sculpture Race, the “World’s First Robot Family”, and a large display of automata from the Cabaret Mechanical Theatre of London.

The works on display are often absurd or humorous, occasionally thought-provoking, and sometimes quite sorrowful.

One exhibit, Esther and the Dream of One Loving Human Family, featured 36 hand-embroidered works by Esther Krinitz describing her Holocaust survival story. This was moving and felt somewhat out of place with the rest of the items on display in the museum.

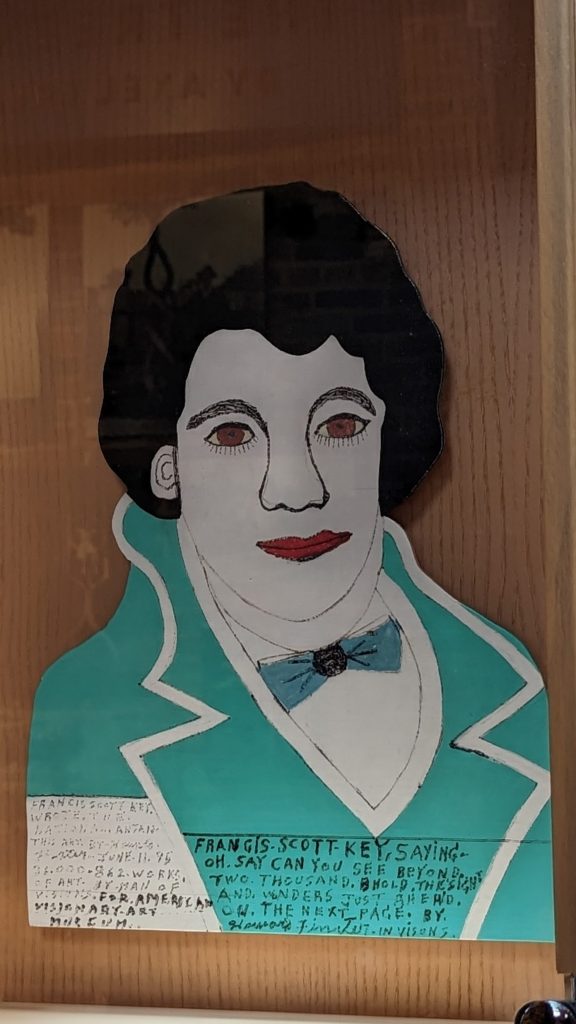

Upon the opening of the museum in 1995, the late Howard Finster, perhaps the best known artist in the outsider art movement, sent the portrait of Francis Scott Key (right) as a gift to the museum. (We recently visited Key’s gravesite in Frederick, Md.)

Besides creating a folk art garden in Georgia that includes more than 46,000 works, Finster also created album covers for R.E.M. and Talking Heads in the 1980s.

Outsider art is often described as art created outside the boundaries of official culture. Many works in the Museum were created by artists with different types of mental illnesses and often illustrate the artists’ struggles to cope with their conditions while also providing some small insight into the mechanisms of brain functions of the afflicted.

The French refer to outsider art as “art brut,” which can be translated as “raw art” or “rough art.” Indeed, many of the works on display share characteristics that seem unsophisticated or disjointed or even terrifying. This can make visits to the Museum a bit unsettling at times, but stepping into the next room may well provide a glimpse of works that are more uplifting in spirit.

At left is a 10-foot high sculpture of Divine, the late Baltimore actor who rose to fame in movies by filmmaker John Waters. The work is by English artist Andrew Logan. Two other works by Logan are on display in the museum.

When it was being planned, the museum was given a plot of land on the south shore of the Inner Harbor with the caveat that they clean up residual pollution from a copper paint factory and whiskey warehouse that had previously occupied the site. The resulting building is now an architectural landmark in downtown Baltimore (see cover photo at the top of this post).

We visited the museum because it was very well-rated, but our experiences were quite different. Jennifer felt constantly reminded that she is an accountant and that perhaps she was the outsider here! She didn’t connect with much of the work at all. Our friend Jen who also tagged along was of a similar mind. On the other hand, Doug enjoyed much of the offerings with delight.