Andrew Jackson, the problematic seventh President of the United States, was born in 1767 in South Carolina, at the plantation farm belonging to his mother’s sister and her husband, the Crawfords.

Or maybe he was born at the farm of a different aunt and uncle in North Carolina.

Or maybe the house in South Carolina was actually in North Carolina before the borders shifted in the early 1800s.

Since none of the buildings generally designated as the birth site of Old Hickory have been extant since the 1800s, it may be that we will never know with any certainty where Jackson was born. This has led to some competing claims and memorial-building conducted by the DAR and both of the states in attempts to resolve the matter. Those sticklers for historical accuracy at Wikipedia diplomatically describe the location of his birth site as “in the Waxhaws region of the Carolinas.”

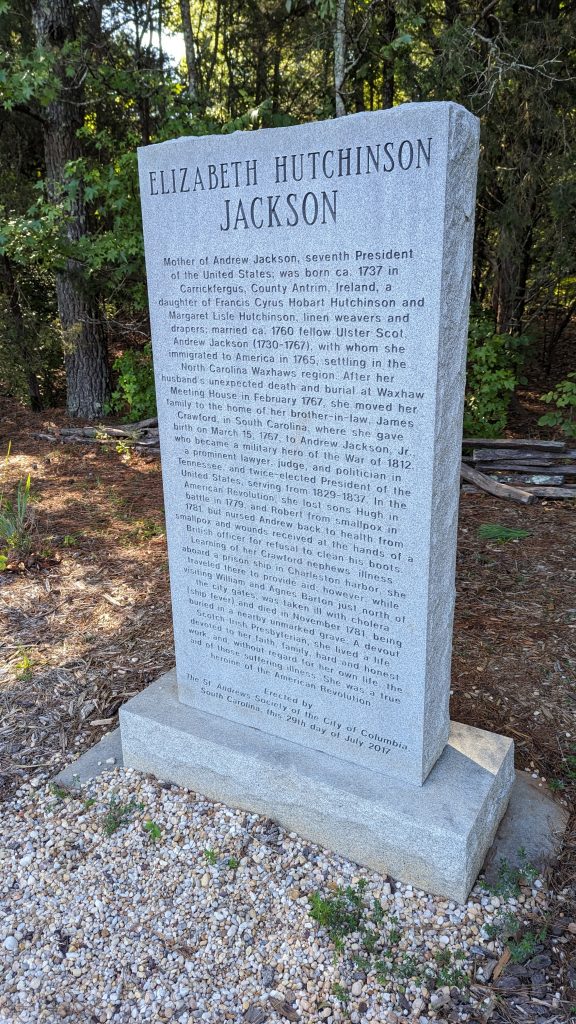

What we do know is that Jackson’s father, Andrew Sr., died from a farming accident just three weeks before Jackson was born. As a result, Jackson’s mother went to the nearby home of one or the other of her sisters and delivered Andrew Jr. there. Jackson variously lived with his mother, brother, and other relatives as a youngster, but his mother died when we has 14 years old, leaving him an orphan. As the Revolutionary War swept through the Carolinas, Jackson witnessed death and destruction at the hands of British soldiers, leaving him with a lifelong hatred of the English as well as a scar on his forehead inflicted by a British officer after Jackson refused to clean the officer’s boots.

Jackson proceeded to (in no particular order) study law, teach school, owned enslaved persons, preserve his honor in a duel by firing into the air, fail to preserve his honor in another duel by killing his opponent (who also shot him), help Aaron Burr beat a federal rap for treason, become a military commander, direct the killing of indigenous peoples and push his Indian Removal Act which resulted in the Trail of Tears, get shot in a street brawl, have two British spies executed which caused problems for President James Monroe, and take up with a separated-but-still-legally married woman whom he married after her husband petitioned for divorce on the basis of her infidelity. All of which seemed to set him up just right to become President. (Yeah, I’m not a fan.)

But a President is a President, so while we were in southern North Carolina and northern South Carolina, we attempted to sort out the Jackson birthplace dilemma and in the process learned a bit more about

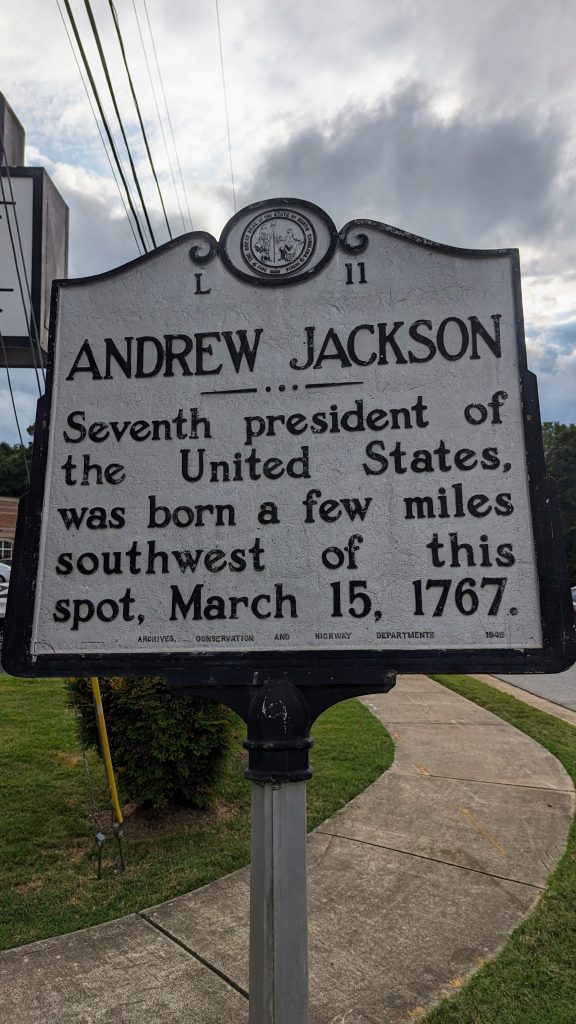

First up was an official state historical marker on Main Street in Waxhaw, N.C., which vaguely pointed out that Jackson was born “a few miles southwest of this spot.”

Another marker a few miles away was erected by the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) in 1910 on what is now known as Andrew Jackson Road. This marker lays claim to the exact spot where the house in which Jackson was allegedly born: “Here was born March 15, 1767, Andrew Jackson, Seventh president of the United States.” This marker conveniently lies just 1200 feet inside the North Carolina state border–could the fact that the N.C. chapter of DAR placed the memorial have anything to do with that? Hmmm….

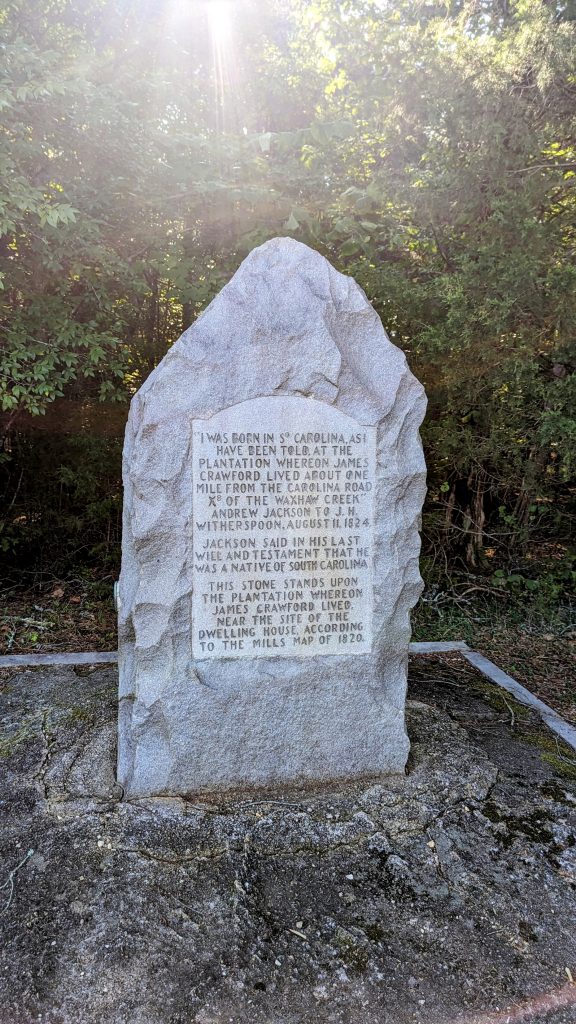

Meanwhile, over in South Carolina, the state created Andrew Jackson State Park, built on the site of James Crawford’s plantation. At the entrance to the park is a 1967 marker erected by the Waxhaws Chapter of the DAR which states, “Seventh President of the United States. Near this site on South Carolina soil Andrew Jackson was born on March 15, 1767, at the plantation whereon James Crawford lived and where Jackson himself said he was born.”

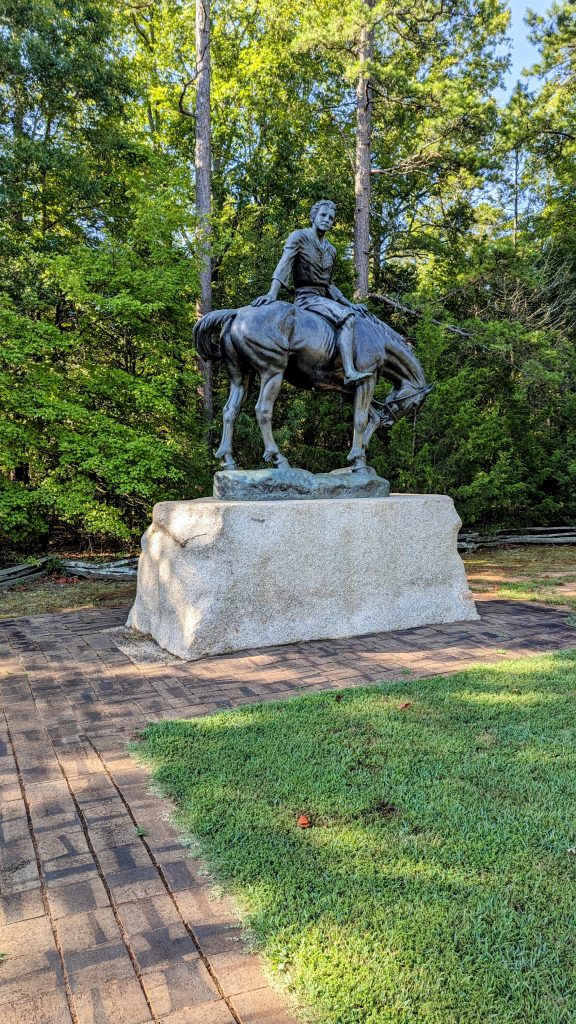

Inside the park, the state has gone all out with markers and monuments and a museum devoted to Jackson. One includes text from Jackson’s last will and testament that states his belief that he was born in South Carolina, while another honors his mother (who did die a heroine’s death in service of her ill nephews who were being held on a prison ship in Charleston harbor). A rather nice statue entitled Andrew Jackson, A Boy of The Waxhaws by Anna Hyatt Huntington is also on the site. There are still more interpretive plaques in the mark, but you get the picture.

The park includes reconstructions of a log schoolhouse (“similar to what Jackson would have attended”) and a religious meeting house (where weddings are held today if that’s your jam), as well as a museum. The small museum includes some historical artifacts and exhibits about Jackson’s life and local history, which only offered cursory mentions of pesky little issues like Jackson’s handling of slavery and native Americans during his two terms as President. We both did find the video documentary of key periods of Jackson’s life to be especially well-done compared to some of the other museum films we have seen.

Jackson died at The Hermitage, his home in Nashville, Tenn., in 1845, but he initially never moved to Tennessee–Tennessee moved to him. After being admitted to the North Carolina bar in 1787, he accepted a post as prosecuting attorney in the Western District of North Carolina. This part of North Carolina later became part of Tennessee, and Jackson moved into the Tennessee political machinery there instead of North Carolina or South Carolina. The rest, as they say, is history.