We often think of the Declaration of Independence as that parchment document that was signed by the founding fathers on July 4, 1776 in Philadelphia, Penn., just as it was portrayed in John Trumbull’s painting that now hangs in the U.S. Capitol Rotunda in Washington, D.C.

Except… the Declaration wasn’t signed by the delegates to the Second Continental Congress on July 4th.

Trumbull’s painting portrays the “Committee of Five” presenting their draft of a declaration to be considered by the Second Continental Congress on June 28, 1776.

The resolution for independence was actually adopted on July 2nd, approved and printed on July 4th, and signed by most (but not all) signers in August.

This is just the kind of mythologized view of history that the Albert H. Small Declaration of Independence Collection aims to correct in the exhibition “Declaring Independence” on display in the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library at the University of Virginia (UVA).

Albert H. Small was a graduate of UVA who built a collection of rare books and manuscripts, especially related to Thomas Jefferson, the University of Virginia (which Jefferson founded), and American history. He donated his collection to the University in 1999, and he and his wife made a substantial donation that supported the construction of a library on campus devoted to rare books and manuscripts. On the first floor of this library, a permanent exhibit was created to highlight Small’s Declaration of Independence Collection.

Small’s collection of letters, documents, and early printings of the Declaration of Independence is considered the most comprehensive, and includes early printings and reprints of the document, letters from signers, and newspaper clippings. Together, these artifacts trace the oft-forgotten history of the Declaration.

In addition, the exhibition’s letters and printed materials shed light on a part of the Declaration’s history that we don’t usually consider: how were the documents and its principles conveyed to residents throughout all 13 colonies, and to the rest of the world? And further, how did the Declaration shape the thinking of future generations, and when did it become an American icon?

On July 2, 1776, the Second Continental Congress passed the Lee Resolution, which stated that the 13 colonies were “free and independent States,” separate from the British Empire. Some historians make the case that the Independence Day should be actually be celebrated on July 2nd as a result of this resolution.

So what happened on July 4, 1776? This is the the Second Continental Congress voted unanimously to ratify the Declaration of Independence which was to be its public explanation of the case for independence. The document approved on this date was the final draft of a declaration created by Thomas Jefferson, based on three weeks of work by a committee consisting of Jefferson, John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Robert Livingston, and Roger Sherman.

The Revolutionary War had actually been underway since April 1775 when the Battles of Lexington and Concord took place, but the Declaration would “officially” explain to the world why the colonies regarded themselves as independent sovereign states no longer subject to British rule.

Overnight, the Congress’s official printer, John Dunlap, worked to typeset and printing the text of the Declaration onto single-sided, printed “broadsides.” These were then distributed to the Colonies by order of John Hancock, President of the Congress. The Small collection includes one of just 25 extant copies of this printing.

On July 6, 1776, The Pennsylvania Evening Post published the Declaration for the first time in a newspaper. Together with the Congressional printing, the newspaper publication helped word to spread across the colonies, and additional newspapers followed suit. Colonies approved their own printings, as well. These were often read aloud in town squares, churches, and military camps.

Meanwhile, on July 19, 1776, the Congress authorized the creation of a formal “presentation” copy of the declaration on parchment, which was signed in August 1776. This is the version that is best known, on display at the National Archives in Washington, D.C.

The Revolutionary War concluded with American independence in September 1783, but hostilities with England resulted in the War of 1812, which in turn led to renewed patriotism during and after the war.

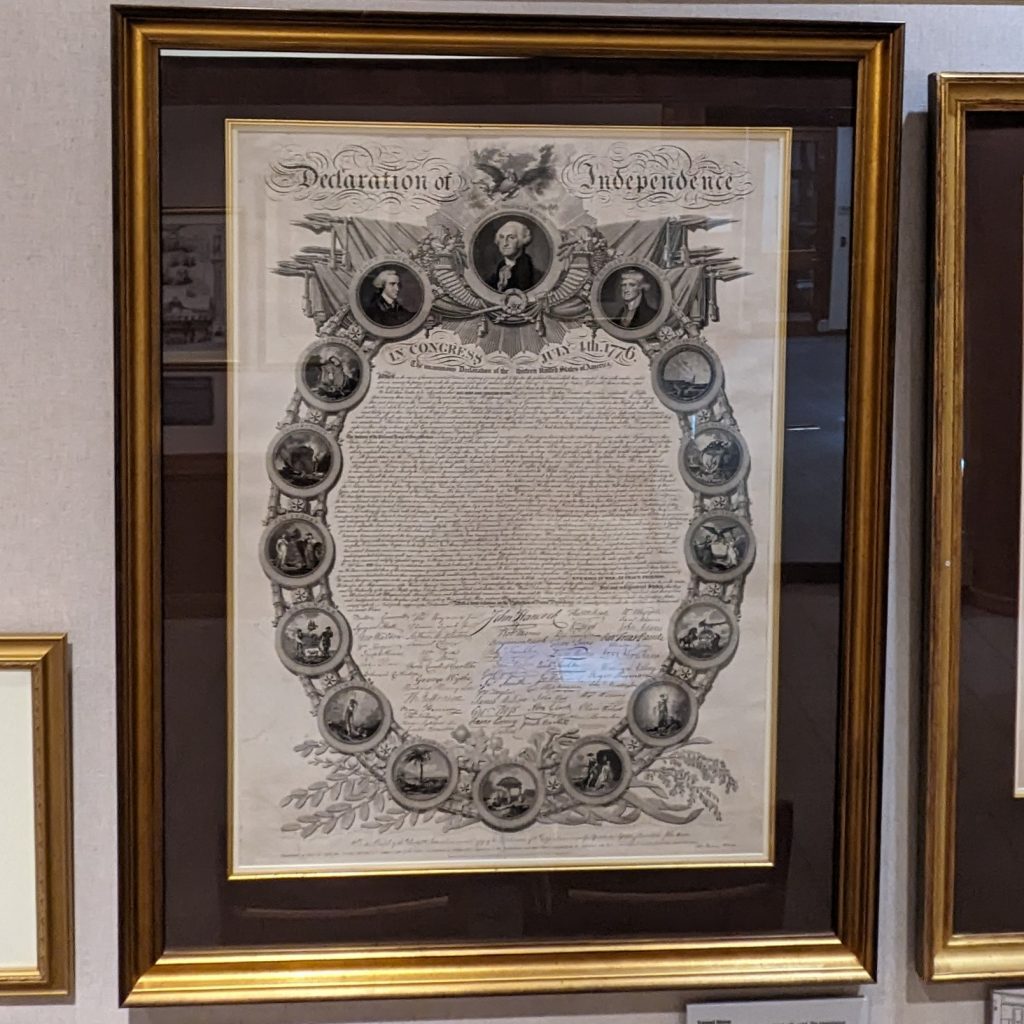

Savvy entrepreneurs capitalized on this interest by printing elaborate, often-illustrated, engraved versions.

Even Jefferson, James Madison, and John Quincy Adams rushed to order editions of these reprints. Several versions are on display in the collection.

In response to this interest, Secretary of State John Quincy Adams commissioned the production of an official facsimile. In order to capture an exact image, the printer moistened the surface of the original signed copy in order to transfer some of the ink from the original onto his copper plate. This would help explain the poor condition of the Declaration now at the National Archives. These and later editions printed on parchment were distributed by order of Congress, including two copies gifted to the Marquis de Lafayette, one of which is on display.

There is much more to the exhibit, including a short documentary film available for viewing on demand. I liked the clipping from a London newspaper that reprinted the text right above an advertisement for the newly-published cookbook, Mrs. Glasse’s Cookery!

History buffs will surely enjoy this short exploration of the most important document in American history.

When I lived in NoNY, our cable company included several Canadian stations. A documentary on the War of 1812 was of special interest. Several critical naval battles between American and British ships occurred along the eastern shore of Lake Ontario, Kingston, Ontario and the terminus of the St. Lawrence River.

Americans are led to believe “we” won this war. Interestingly, the Canadian documentary begs to differ. Rather, the film concluded there was no “winner.” Due to lack of men and materiel, a “draw” was a more accurate conclusion. The Treaty of Ghent signed by Britain and the United States ended the war. Per Wikipedia:

“Treaty of Ghent, (Dec. 24, 1814), agreement in Belgium between Great Britain and the United States to end the War of 1812 on the general basis of the status quo antebellum (maintaining the prewar conditions).