I was in fairly high hopes about our Confederacy experiences-to-be after our stop at the White House of the Confederacy, but visits to Stonewall Jackson sites in Virginia put an end to that expectation.

We were both a bit conflicted about giving money to organizations that preserve the legacy of the South’s Civil War ideology, but also both feel strongly that educating ourselves about all sides is important, too.

Thus it was that we found ourselves experiencing a string of sites related to Confederate General Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson.

Jackson was born in 1824 in what is now West Virginia, but growing up brought many trials.

When he was still a toddler, his younger sister and father both died of Typhoid fever, leaving his mother in debt with three children to raise. When his mother remarried a few years later, the children were sent to live with various relatives, as the step-father did not want them around.

Though Jackson was happy living with his indulgent grandmother, she died within a few years, and his mother died shortly thereafter.

Thomas, still just a child, was then sent to live with an uncle, who owned a grist mill. This uncle educated Jackson in business and farming.

In yet another blow, his older brother succumbed to tuberculosis when Jackson was 17, leaving him with just his sister, Laura.

The two remained close through most of their lives, though Laura being a staunch Unionist did cause some serious strain in their relationship at the end.

At age 18, Jackson entered the United States Military Academy at West Point, NY. He finished his first year at the bottom of his class, but due to sheer determination, he worked his way up to graduated 17th of 59 cadets 4 years later.

At this point, Jackson began his career in the United States Army, and soon found himself fighting in the Mexican-American War. He served with distinction and also met for the first time Robert E. Lee, later leader of the Confederate forces.

In 1851, at the age of 27, Jackson became a Professor of Natural and Experimental Philosophy (what we would today call “Physics”), as well as Instructor of Artillery, at the Virginia Military Institute (VMI) in Lexington, Va.

He was, by all accounts, not an especially “good” professor, especially during his first few years of his decade at the Institute. He was not an expert in his subject, so he rehearsed for each class by memorizing the prepared lectures beforehand. If a student asked a question, he simply rewound and restated what he had previously said. He was, however, talented as an Instructor of Artillery.

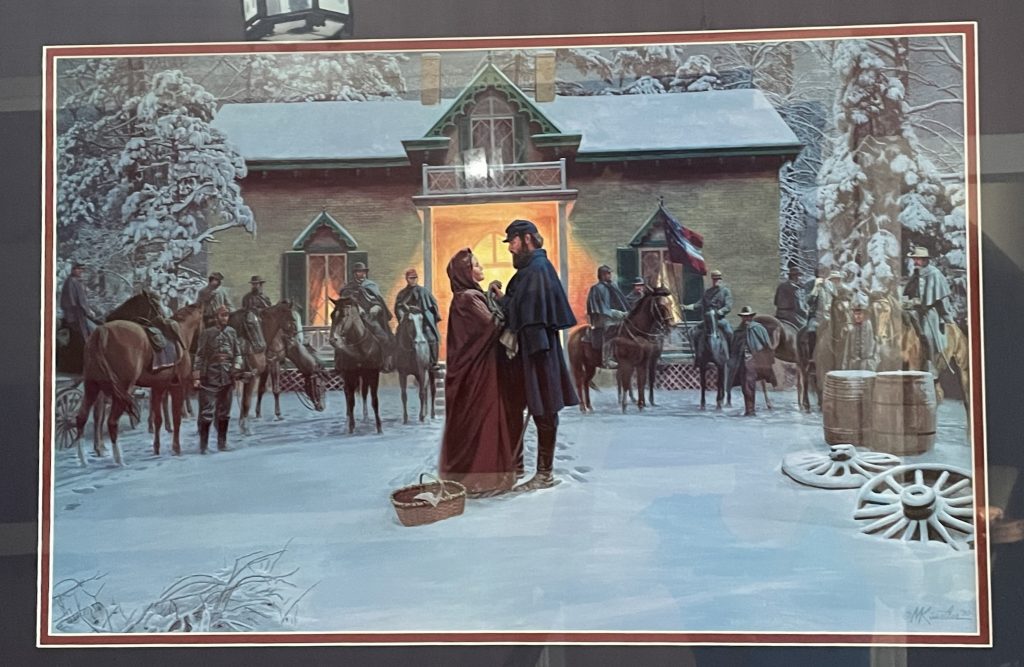

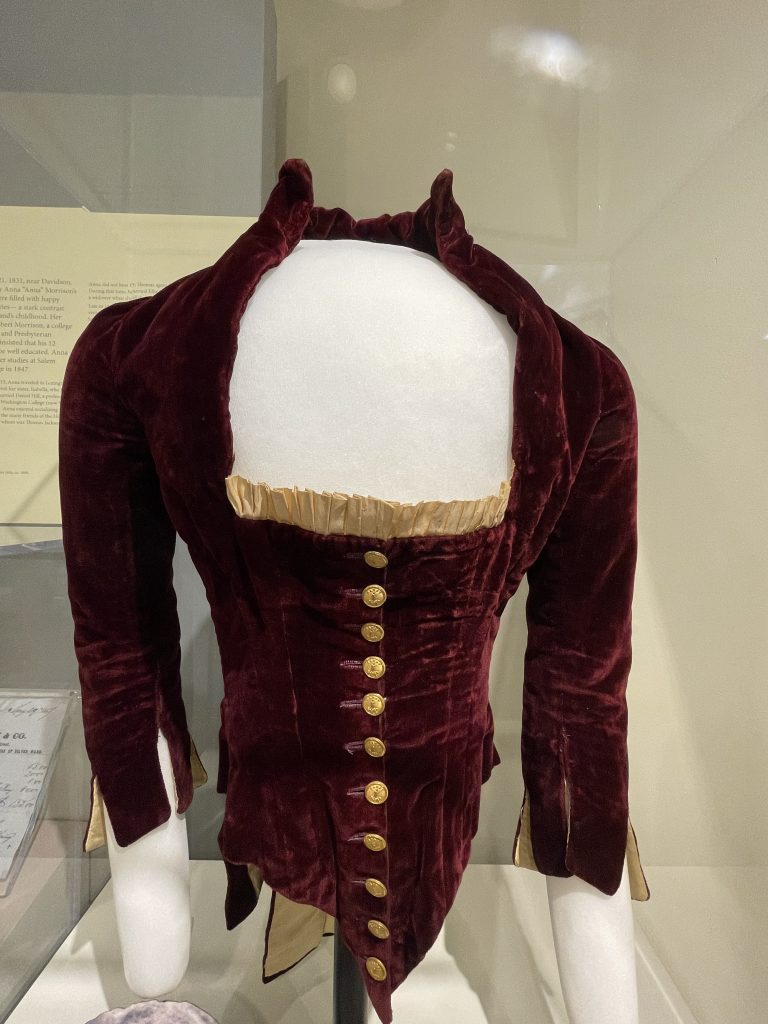

During his stint at VMI he met and married Elinor “Ellie” Junkin. Unfortunately, she and their baby died in childbirth just a year later. Three years later he married Mary Anna Morrison. A year later their first child died after just a month. Finally, in 1862, when Jackson was 38, the couple welcomed a healthy baby girl –– but Jackson was only to see her twice before his own death.

The Stonewall Jackson House in Lexington was the only home Jackson ever owned. Jackson purchased the home in 1858, and he lived there just two years with Mary Anna during his time as a VMI professor. After he left VMI in 1960 to serve in the Confederate Army, he would never return to the house.

We took a “Master Guide” tour of the house with a guide who appeared to suffer from an excess of Jackson hero worship. For instance, we learned that Jackson most likely really didn’t support the war and only served because he was afraid for his home and family. The fact that Jackson owned six enslaved persons didn’t seem to impact his decision about taking up arms against his country. As we say up north, WTF?

Jackson earned his famous nickname at the First Battle of Bull Run (First Manassas) on July 21, 1861. When things looked bleak during fierce fighting, Jackson led his forces from the front. Jackson’s colleague General Barnard Elliott Bee Jr. then rallied his troops by declaring, “There is Jackson standing like a stone wall. Let us determine to die here, and we will conquer. Rally behind the Virginians!”

Jackson served with honor and distinction in numerous battles over the next two years (Wikipedia lists more than 20 Civil War battles in which he took part). He is considered one of the most gifted tactical commanders in U.S. history.

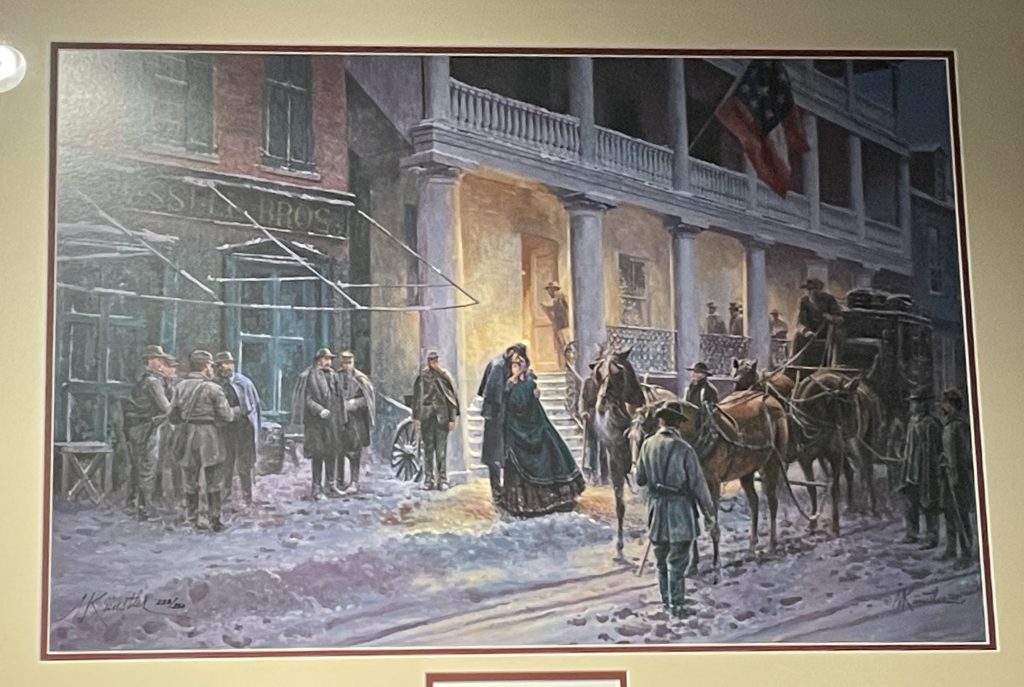

By November 1861, Jackson had set up headquarters in Winchester, Va., while commanding the 4th Virginia Infantry in the Confederate States Army. His wife joined him there the following month. From this house, Jackson planned his campaigns in the Shenandoah Valley, and would remain here until shortly before his death.

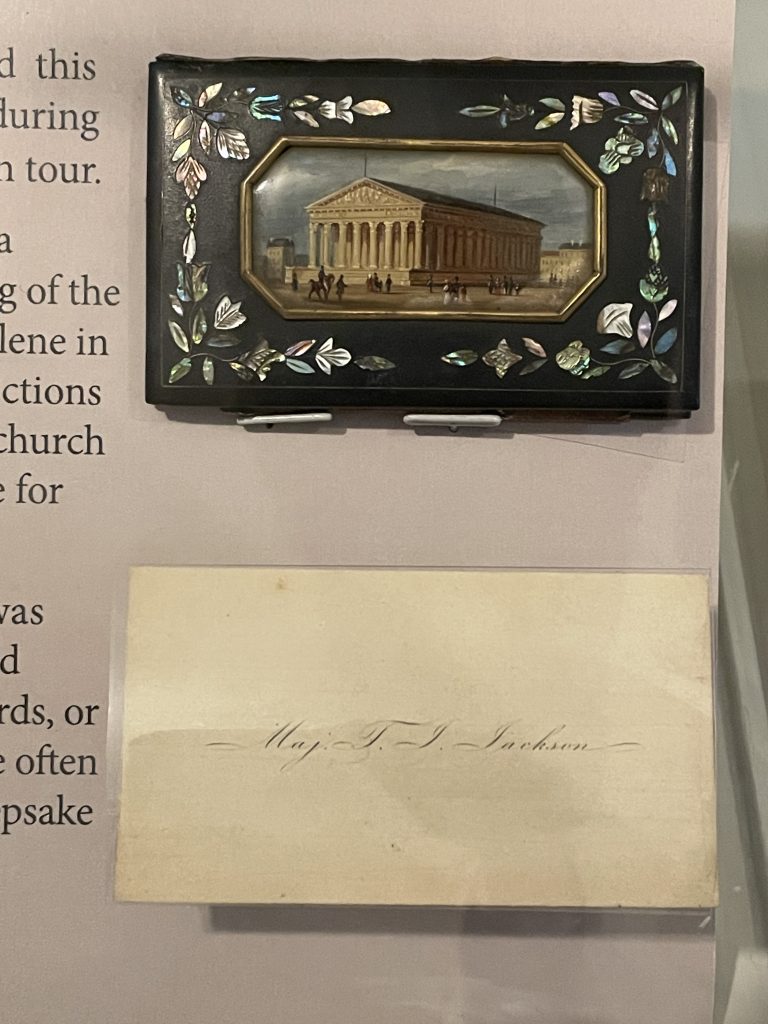

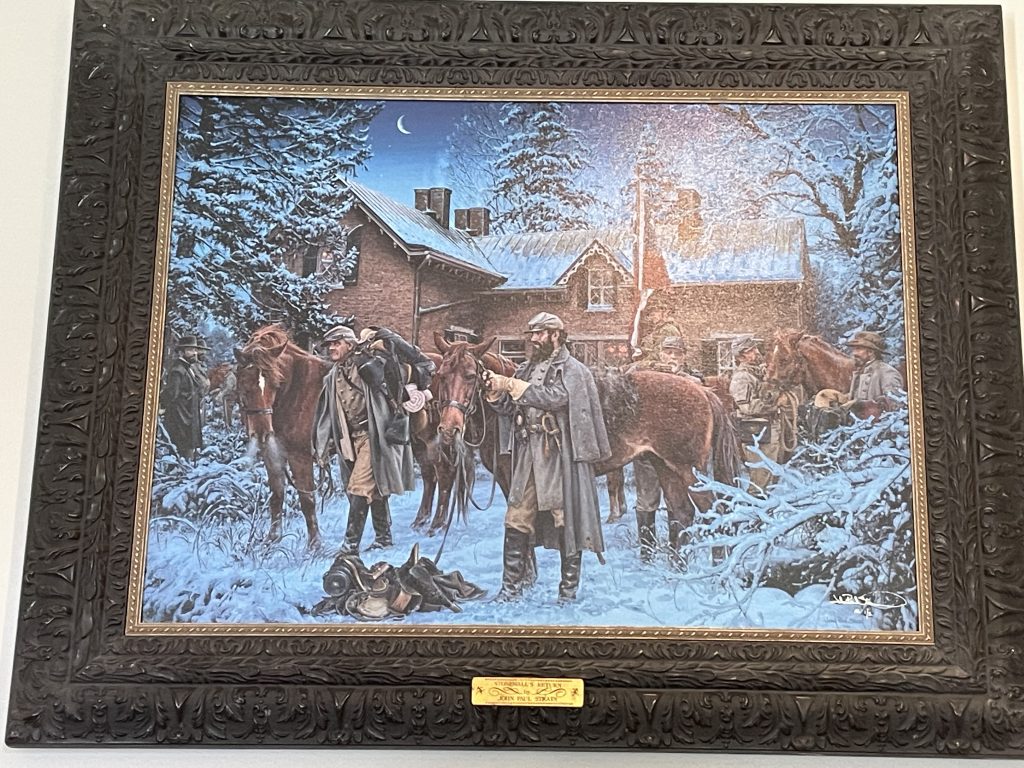

The home where Jackson established his headquarters is now a museum, Stonewall Jackson’s Headquarters. This site includes a rather extensive collection of original pieces tied to Jackson — so much that it effectively serves as a shrine to Jackson. The “cult” of Jackson began shortly after his death and continued to grow as the Lost Cause Mythology, and many of the artifacts on display are relics of this Jackson mania.

Our enthusiastic tour guide kept our tour going for a good 90 minutes when probably half that was all that was needed. At one point he referred to the “Confederate flag we all know and love,” and the gift shop was overflowing with Confederate flag memorabilia. I started feeling itchy.

On May 2, 1863 Jackson was accidentally shot by friendly fire. His left arm was amputated, but eight days later he died of complications and pneumonia.

As he lay dying, Lee sent a message: “Give General Jackson my affectionate regards, and say to him: he has lost his left arm but I my right.”

Jackson’s wife rushed to his side with their daughter, where he got to hold her for just the second time. Her life, too, was cut short, dying of typhoid when she was just 26 years old.

After his death, stories of Jackson’s military service reached legendary levels, where he became an integral part of the Lost Cause ideology.

Jackson is buried in Oak Grove Cemetery in Lexington, where a large monument to him stands, erected in the early 20th century. His original much more modest grave marker still stands.

When we visited, Doug noticed the ground around the statue had a number of lemons on it. We later learned that General Richard Taylor wrote in his war memoirs of Jackson’s special love of lemons.

However, this fact was a surprise to Jackson’s family, staff, and fellow soldiers. Nevertheless, the myth of Stonewall’s lemons still endures.

In addition to Jackson’s home and headquarters, there are a number of items on display relating to Jackson at the VMI Museum in Lexington, including his taxidermied horse and the raincoat he was wearing when he was fatally shot, still with the bullet hole intact.

Jackson’s death site and the burial site of his arm (yes, seriously) are still Jackson sites we hope to see on our travels.

One thought on “Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson in Virginia”