Doug and I arrived early to the National D-Day Memorial in Bedford, Va., planning to take the first tour of the day. We made our way through their small museum, and then I ran over to get a peek at the memorial before it filled up with people. And so it was that I was crying before the tour even started.

The memorial is extremely powerful. Often we feel that places such as this suffer from stereotypical imagery – sweeping arches over here, tall columns over there, giant eagle this way, state flags all around, waterfalls, wreaths (you get the picture).

I felt like this memorial was the opposite of “as expected,” though Doug was not quite as moved as I.

By May 1944, the Western Allies were ready to launch what they hoped would be their greatest blow of the war, a cross-channel invasion of northern Nazi-occupied France, an operation code-named Overload Neptune (Overlord was the code name of the actual invasion; Neptune was code for getting the troops across the English Channel for the invasion).

The invasion was the coordinated efforts of twelve nations, overseen by General Dwight D. Eisenhower as the Supreme Commander.

The invasion was much-delayed, but it would be a surprise to the enemy forces. The plan was to attack at Normandy, when the Germans expected it instead at Pas de Calais (where the English Channel was narrowest). Even though the Normandy location was relatively low on defensive troops (most were stationed at the expected point of attack), the Germans had still placed miles of obstacles, mines, concrete bunkers, ditches, and artillery.

In addition, the seas were rough and the weather unpredictable; the terrible weather had already delayed the attack by a day.

Advance airborne troops were dropped behind enemy lines just after midnight on June 6, 1944 working to blow up bridges and railroad lines, making it difficult for the enemy to rush to the shore when they realized the attack was underway.

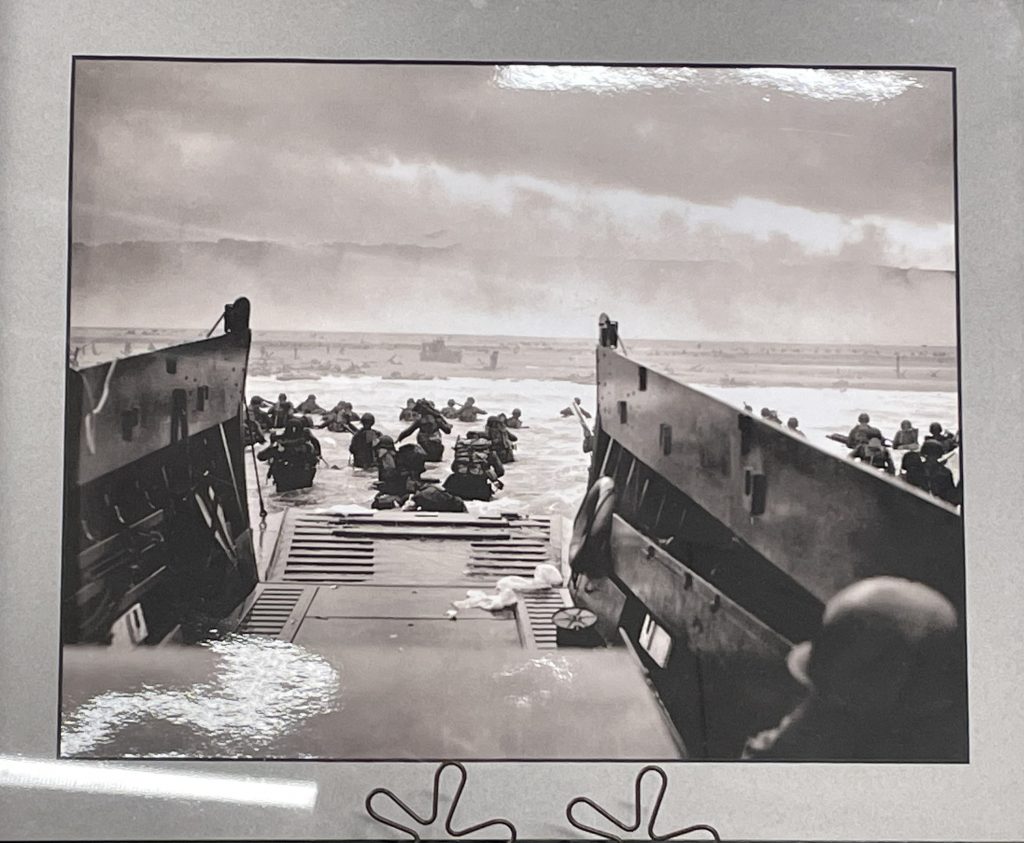

Hours later the largest amphibious landing force ever assembled made its way towards the beaches at Normandy, the Americans in flat-bottomed Higgins boats.

The seas were rough and many men were seasick after covering 10-miles in this tempest. Cold and drenched, they must have been in terrible fear of what was ahead, as well.

There were five landing zones, with the Americans landing at Omaha and Utah beaches; the fiercest fighting was at Omaha, where the enemy was positioned atop steep cliffs, pinning the troops on the beach. “If you (stayed) there you were going to die,” Lieutenant Colonel Bill Friedman said.

Of the 35,000 men who came ashore, 4,700 were killed, wounded, or missing, a loss rate of more than 13 percent.

By nightfall, 175,000 Allied troops had made it ashore; the successful invasion was one of the great-turning points of not just the war, and thus history itself.

“D-Day” is the start date of a military operation; D-1 is one day before, D+2 is two days after, for example. All military operations have a D-Day, but the invasion of Normandy on June 6, 1944 was so consequential and historic, it has simply become “D-Day.”

The Memorial, which opened in 2001, sits on 50 acres in the Blue Ridge Mountains. The town of Bedford was chosen because of the town’s heavy sacrifice in the war.

Forty-four soldiers, sailors, and airmen from the town and county of Bedford, Virginia, participated in D-Day, and twenty of them died that day (four more were killed during the rest of the Normandy campaign).

Though other towns in the U.S. lost more people on that day, Bedford was a small town of 7,000, and proportionately, they suffered the greatest loss of any American town during the campaign.

This town’s story is told in the book The Bedford Boys by Alex Kershaw, which Doug recommends and which I have just started.

The memorial is laid out in three plazas, each one level up from the prior.

The Reynolds Garden in the first plaza represents the planning and preparation phase.

It is laid out in the shape of the Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force combat patch.

The stylized English garden is a connection to England, where planning for the invasion took place.

The Gray Plaza is for the crossing-the-channel and landing stages of the invasion, with representations of the water, beach obstacles, soldiers struggling ashore, and part of the Higgins craft used to land the soldiers (see cover photo).

The periodic jets of water spurting from the water replicate sporadic gunfire, a jarring reminder of the hazards of the day.

The wall surrounding the plaza has the names of the 2,502 Americans who lost their lives on one side, and 1,913 names of Allied losses on the other side.

The Estes Plaza celebrates victory and includes the 44.5-foot-tall Overlord Arch along with the flags of the Allied nations that served.

The random jets of water simulating gunfire on the Gray Plaza are what pushed me to tears.

It is really incomprehensible what these men faced, how completely terrifying this experience must have been.

Doug suggested I watch The Longest Day, released in 1962 and considered to be a quite accurate representation of the day.

The film is three hours long, and there’s not much way of character development or “getting to know” any of the participants, but I think that’s rather the point.

The movie focuses on the long hours of waiting (tense for the leaders, rather boring for everyone else) leading up to the answer to the question “will we invade tonight or not?” and then the horrific scenes of the invasion.

It was very intense, and I thought it was excellent.

The brochure lists Jim Brothers as the principal sculptor, along with sculptors Matt Kirby and Richard Pumphrey. The Memorial architect was Dickson Architects and Associates.

Wow, this post is really moving. Good job.

Thanks!