Even though we’ve previously been to a regular viewing of the Gettysburg Cyclorama, we were interested in their extended “An Evening with the Painting” program. Gettysburg is not too far from where Doug’s family lives, but the special Evenings were few and far between. It took us a while to find a night we were in town and for which tickets were available!

The after-hours program began with a 45-minute presentation by Chris Brenneman, a Licensed Battlefield Guide and one of the authors of The Gettysburg Cyclorama: The Turning Point of the Civil War on Canvas. He explained the history of cycloramas in general and gave analysis on the Gettysburg cyclorama in specific, including pointing out some errors in the painting.

Afterwards we got to go under a small section of the painting, and then go up “on deck” where he walked us through the painting and some of the features he had discussed.

Cycloramas were big attractions back in the day (remember this is pre-television and pre-radio, even!). Chris called them the “movies theaters of their day.”

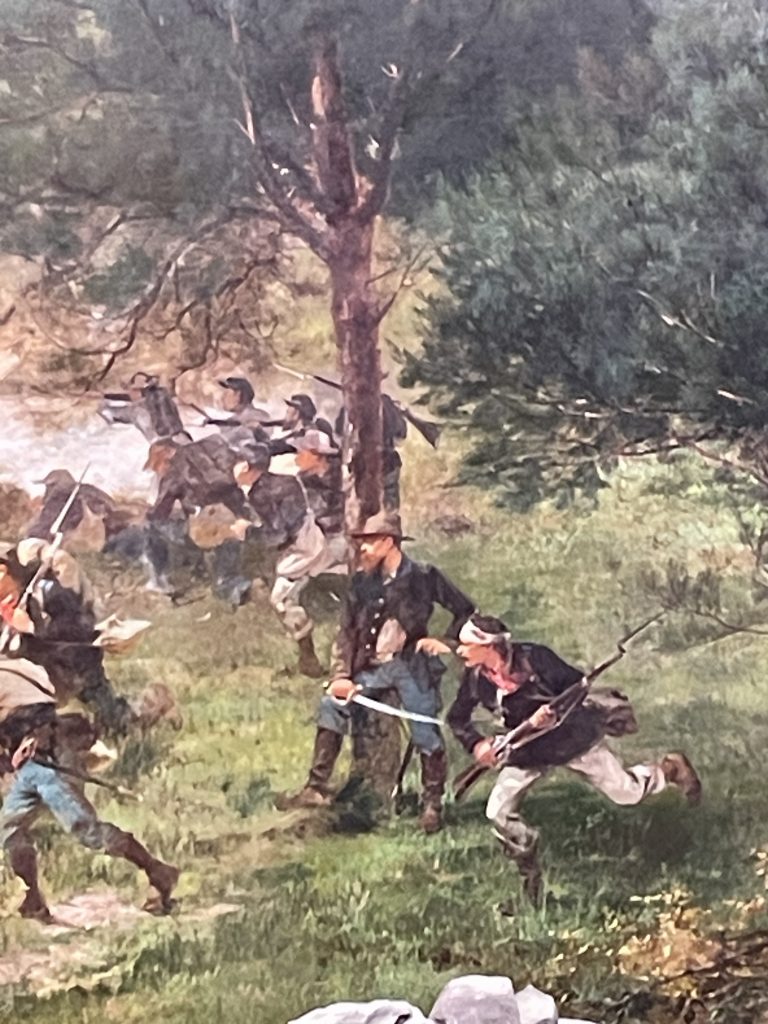

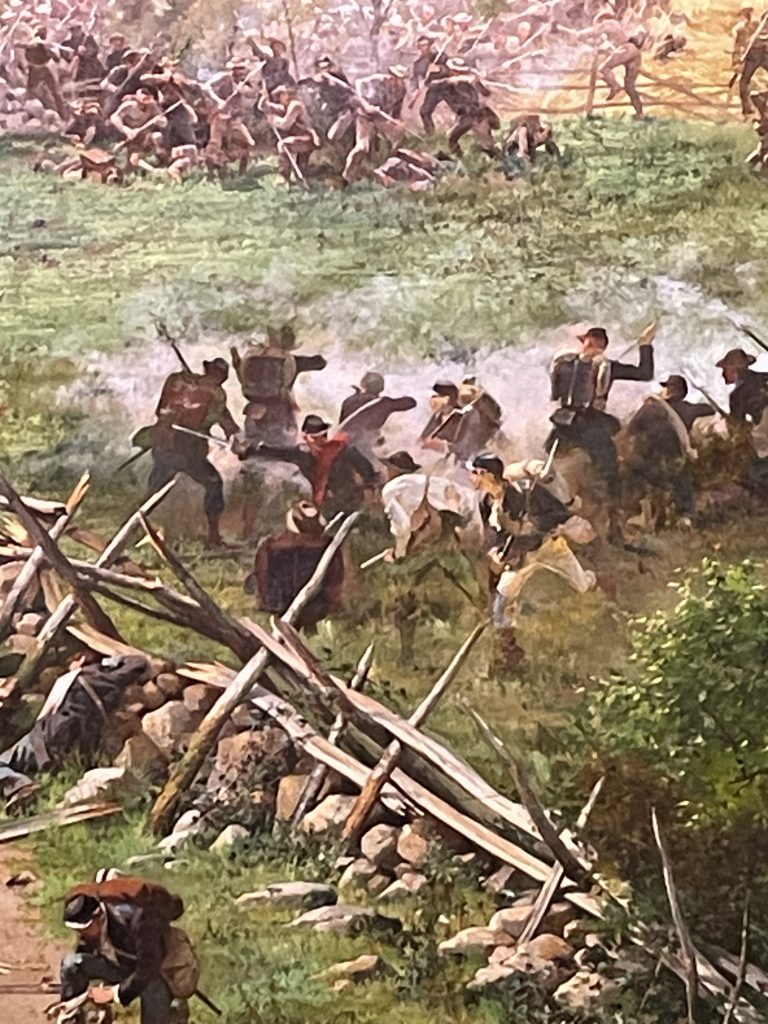

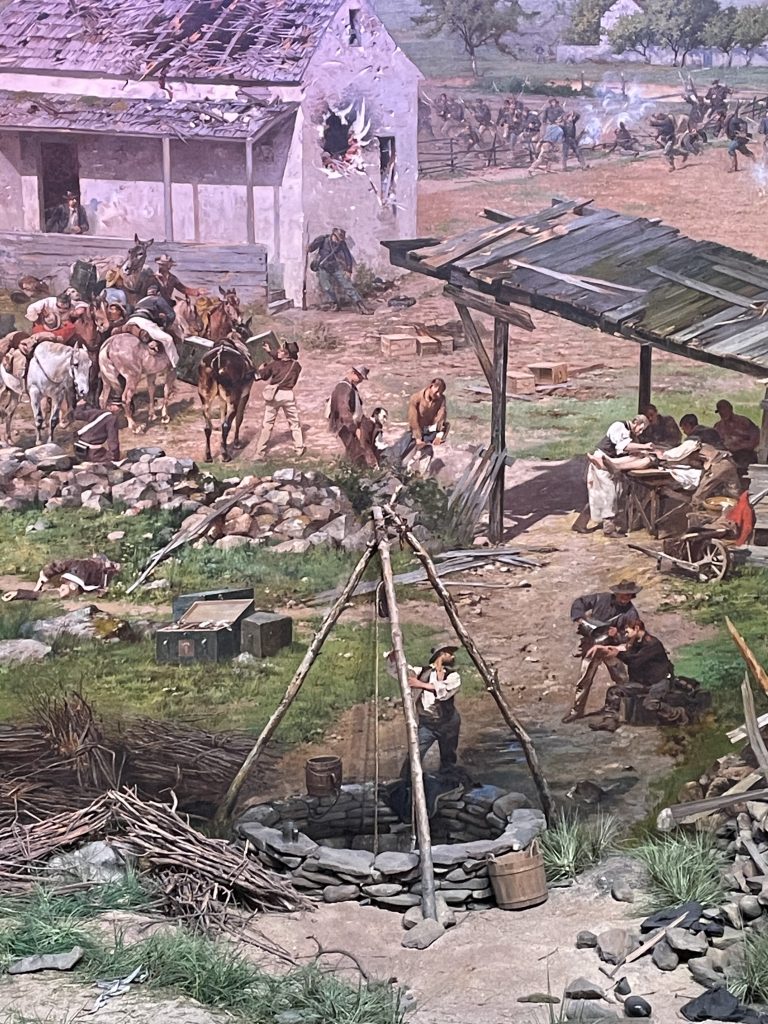

A cyclorama has a few criteria that makes it more than “just a painting.” Besides being circular and providing a 360° experience, it also has scenery at the bottom that extends towards the viewer, blending the flat painting with 3-D objects (the “diorama”).

Cycloramas are hung from ropes with weights at the bottom that give the painting an inward curve at viewer-level (this is only visible when standing at the base). It has a low ceiling over viewers that obscures the top of the painting, and finally, the viewers are on an elevated platform so that they look directly into the middle of the painting.

The Gettysburg battle scene was painted in four very similar versions in the 1880s, one each for initial display in Chicago, Boston, Philadelphia, and Brooklyn. Due to their popularity, you might think they were hurriedly put together, but that’s not the case.

French artist Paul Philippoteaux was hired for his expertise, having completed a number of other cycloramas in Europe; he hired professional artists, each with their own specializations in people, landscapes, horses, etc.

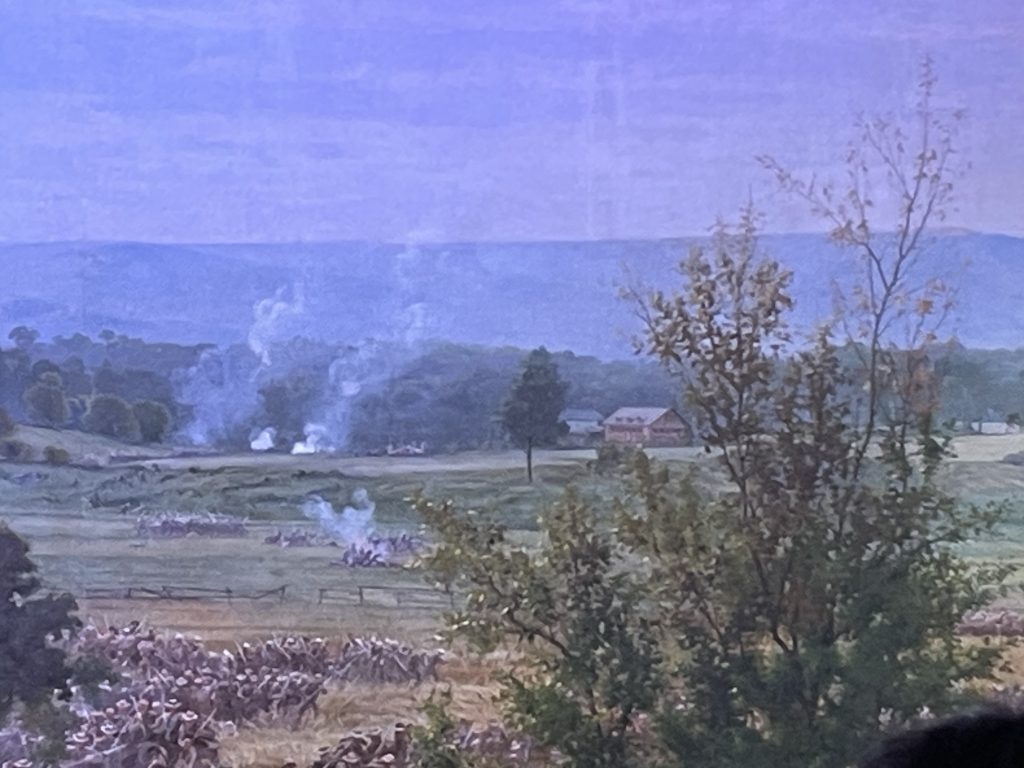

Photographs were made of the actual Gettysburg battlefield landscape (from an elevated platform, naturally), with horses placed at varying distances to be sure scale would be correct. The artist spent several weeks at the site, and several months researching the battle, including interviewing generals Hancock, Doubleday, Howard, and Webb.

Much attention was paid to who was where in the actual painting; even Robert E. Lee, who of course was not in the battle himself, is very tiny in the distance but holding his binoculars and watching the horror unfold. The average viewer would not even be able to pick him out, unless he’d brought binoculars along, but Lee is there nonetheless!

The painting has amazing detail in facial features, uniforms, soldier kits, etc.; the more you look, the more you see. One thing that is not accurate is the amount of blood; they held back on the gore so as to not overexcite the delicate ladies who would be viewing the end result.

“So perfect is the illusion that it is impossible to tell where reality ends and the painting begins,” as the Boston Advertiser wrote.

The painting measures 42 feet high and 377 feet long, one of the largest free-standing paintings in North America, and took longer than a year-and-a-half to complete. The scene is of “Pickett’s Charge”, which happened on the third and final day of the infamous battle, on July 3, 1863.

The painting in Gettysburg (the “Boston” version, the 2nd of the 4 made) is the only one of the four paintings done by Philippoteaux’s team to survive, and even it barely made it.

In 1892, after the public lost interest in cycloramas, the painting was stored rolled up in an outdoor shed, subject to New England weather. In 1910, a Newark, N.J., department store owner purchased the diorama, then proceeded to cut it up and display it in the interior courtyard of his store. In 1913, the cyclorama’s pieces were put back together and placed on display in a purpose-built round building in Gettysburg.

The cyclorama was purchased in 1942 by the National Park Service, and, after some restoration work was undertaken, became the centerpiece of a new visitors center that was opened in 1961.

Despite the work done before the cyclorama was hung in the visitors center, the painting was a far cry from its original condition. While some of the weather-related damage to the canvas was fixed, a twelve-foot section of the work was still missing, and fourteen-feet of sky had been entirely removed from around the top. It was in this condition that the cyclorama was viewed by millions of visitors until 2005 when the visitors center was closed.

From 2005-2008, a $13-million restoration did its best to repair the previous damage and “repairs,” and the removed sections were sewn back on.

Most significantly, a new $100 million Visitors Center was built in a new location in a partnership between the Gettysburg Foundation and the National Park Service (with private donors picking up 70% of the cost). The key feature of the new building was a home created especially to showcase the cyclorama.

The Gettysburg Cyclorama is one of only two Civil War cycloramas remaining in the U.S., the other being the Battle of Atlanta, which we had just seen a few weeks earlier. In 2015 we visited the Battle of Waterloo cyclorama in Belgium, as well.

I think the best review of the painting can be found in a letter from General John Gibbon to General Henry Jackson Hunt in 1884 (both men served at Gettysburg): “Whilst in Chicago I went to see the battle of Gettysburg three times, and you may rest assured you have got a sight to see before you die. It is simply wonderful & I never before had an idea that the eye could be so deceived by paint & canvas.”

My kid-memory of this in the early ‘60s is that it was perhaps much the worse for wear and in a more cramped space. Glad to see it’s been beautifully restored and that you got to take part in a descriptive program.

It’s hard to believe it’s made it to the life it has now! Things looked pretty desperate for a long while.