In 1996, the powerful docudrama Andersonville aired on television. I remember being horrified/fascinated by it, and reading a book about it soon thereafter.

Ever since I’ve wanted to visit the camp, and we were finally able to do so on our way through Georgia towards Florida.

The Andersonville National Historic Site near Andersonville, Georgia, is where the notorious Confederate prison Camp Sumter (now known simply as “Andersonville”) was located.

Also on site is the Andersonville National Cemetery, state memorials, and the National Prisoner of War Museum.

The prison was established here in February 1864 as it was close enough to a railway line to accommodate prisoner transport while being far enough away from the main battle lines to discourage escape attempts. It was only in operation through April 1865, when it was liberated by the Union army, but in that short time, an enormous amount of misery and suffering took place within its boundaries.

Of the 45,000 Union prisoners that were held there (in total, not at all at once), nearly 13,000 of them died due to inadequate food and water, lack of shelter, and unsanitary conditions. The primary causes of death were scurvy, diarrhea and dysentery.

The prison site was ultimately 26.5 acres, built to hold at most 10,000 men. Within a few short months after it opened it already held 12,000 men. By August of that first year, there were nearly 32,000 prisoners inside its stockade walls.

Not all of the site held prisoners. Some of the cleared area was used for a hospital, the Confederate soldiers’ quarters, bakery, latrines, etc. But let’s just say all of the space was available for prisoners –– that’s 1,200 men per acre (best case scenario). Imagine a place you know to be an acre or half acre and then try to imagine 1,200 or 600 men living in it.

But wait, there’s more. There was no housing was built for prisoners. The men were literally put in a field in Georgia in the summer and told to figure it out.

Of course, 1864 was an oppressively hot summer, making the situation even worse. There was no protection from rain and storms. In winter, there was no fuel for fires to generate heat.

To make matters worse, the water supply was a mere stream (and not even that during dry spells). Even at full flow, the stream could obviously not support tens of thousands of prisoners.

This single water source served not only to provide drinking water, but also water for bathing, and for the soldier’s “sinks” — which is what they called their latrine.

To say that the water was constantly filthy is an understatement.

If that wasn’t enough, the bakery and guards’ facilities were located upstream of the camp, so by the time the water arrived to the men, it was a foregone conclusion that dysentery, diarrhea, and typhoid would affect the bulk of the captives.

While regular Confederate soldiers originally served at the prison, these eventually were needed on the front lines, so a motley crew of untrained senior citizens and young teenage boys was rounded up to serve as guards.

The prison was chronically under-supplied with food. The Confederate army was struggling to feed its own soldiers, never mind its prisoners.

Andersonville prisoners became severely emaciated and suffered from scurvy due to the lack of vitamin C in their diets. And the men were perpetually covered in lice.

Prisoner Robert H. Kellog wrote in his diary on May 2, 1864:

As we entered the place, a spectacle met our eyes that almost froze our blood with horror, and made our hearts fail within us. Before us were forms that had once been active and erect;—stalwart men, now nothing but mere walking skeletons, covered with filth and vermin. Many of our men, in the heat and intensity of their feeling, exclaimed with earnestness. “Can this be hell?”

The number of prisoners was so high in the camp because at this point in the war the North and South were not exchanging prisoners. There seemed to be two reasons for this. One was that the South refused to exchange black Union prisoners, and the Union would not agree to exchanges without.

The other was that both sides recognized that returned prisoners equaled soldiers for the “other side” to carry on the fight.

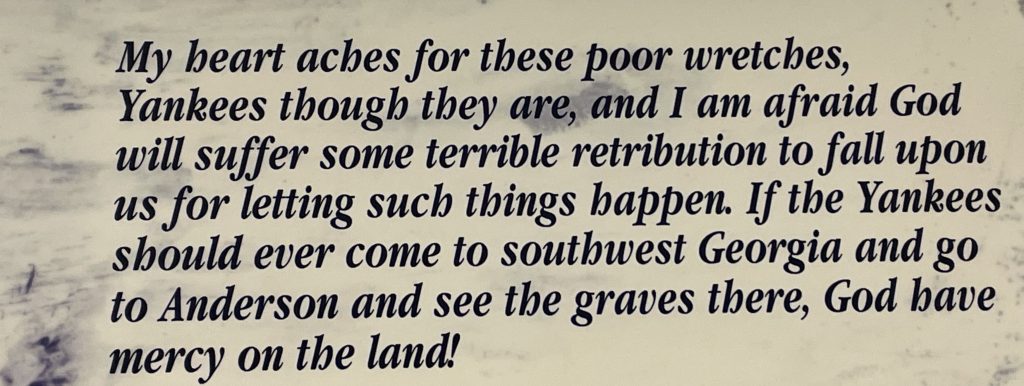

Conditions were so poor that even the commander of the prison, Captain Henry Wirz, allowed five Union prisoners to travel to Washington to petition for prisoner exchanges. The petition failed, and the prisoners returned to the camp.

When Andersonville Prison was liberated by the Union Army in May 1865, the prisoners were described as “human skeletons amid hellish scenes of desolation.”

Because of the high mortality rate, the dead were buried in mass graves.

Thanks to prisoner Dorence Atwater, who worked in the hospital and smuggled out a secret list of those who had died, most of the graves were eventually identified. About 500 graves remain unknown.

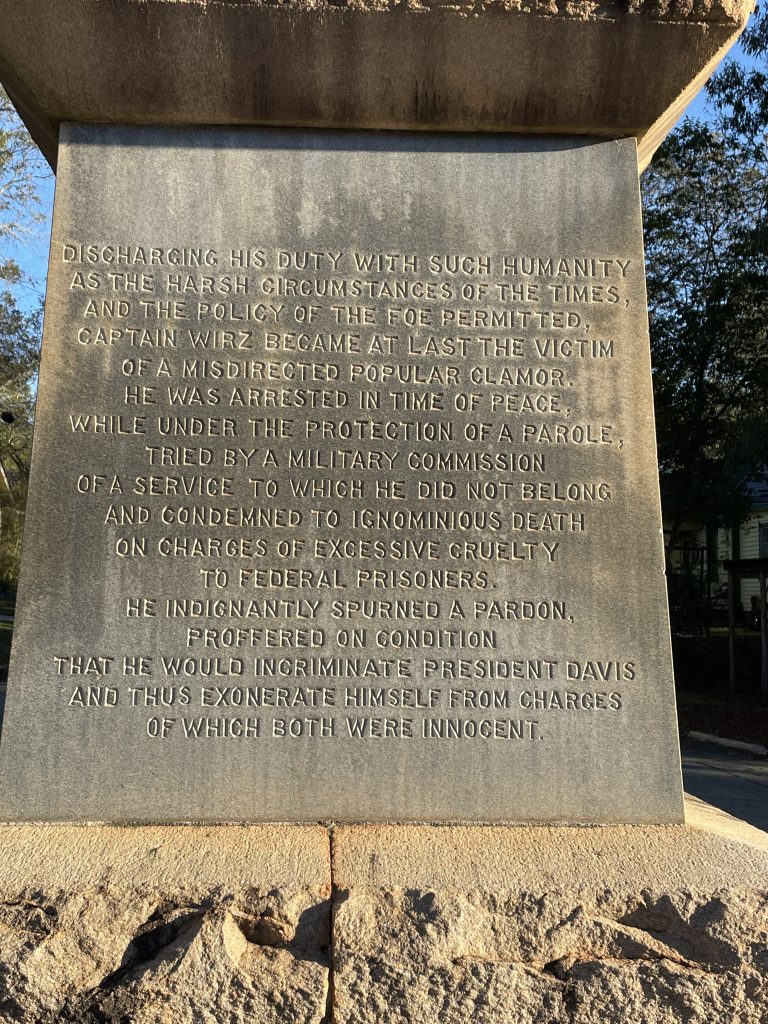

After the war, camp commander Captain Henry Wirz was tried by a military tribunal on charges of war crimes.

Though it does seem that he attempted to get more food for the camp (his own guards were also suffering under the food shortages), his defense used the old “I was only following orders” tactic while at the same time refusing to implicate any of his senior officers. During Wirz’s trial, more than 140 guards, Confederate officials, prisoners, civilians, and Federal officials testified about his management of the prison.

Wirz was found guilty and hanged in November 1865. Execution was a relatively rare outcome of the more than 1,000 military tribunals that were held after the war.

The NPS audio tour seemed to suggest that while, yes, what happened here at Andersonville was not good, the North had bad prisons and high death rates, too.

But the park’s brochure shows that about 15% of Union prisoners died while held by the south and 12% of Confederate prisoners died while held by the north. Andersonville’s death rate was nearly 29%, not even remotely in the same ballpark.

In the interest of fairness, I will say that the Elmira prison camp in New York had a near 25% mortality rate, with nearly 3,000 of its 12,000 prisoners dying.

While what happened at Andersonville is truly horrific, I was not as moved as I thought I would be. I normally cry all through something like this, but the site today is mostly just a big field. There is a very small area with a bit of reconstructed stockade and some homemade shelter examples, but I think due to its small size it fails to convey the horror of what happened here.

In addition, today it is clean and fresh. You must use your imagination to conjure up the swampy fields and horrific stench. There’s also not much by way of contemporaneous photographs of the site (it being 1865, after all).

The Prisoner of War Museum (a memorial to all POWs, not just those at Andersonville) is also located at this site. We watched the film in the Visitors Center, visited the adjacent National Cemetery, saw the state memorials erected by veteran organizations, and did the driving tours of both the prison and cemetery. I don’t think we could have done any more, and yet remained strangely unaffected.

The two most recommended books on Andersonville are Andersonville#AD by MacKinlay Kantor and John Ransom’s Andersonville Diary#AD by John L. Ransom.

A relative of my mom’s, a ~14 y.o. Union bugle boy from far western PA, was captured and sent to Andersonville. Upon his release, the Army/Federal Government gave him a patch of land ostensibly for farming just over the PA border in Ohio. He never married and lived in a rundown shack. When my mom was 8-9 (c.1930) her family visited this man. Her clearest recollection was his beautifully polished brass bugle in the midst of abject poverty.

Wow, that story is amazing!