I’m not sure what to make of Pamplin Historical Park (PHP) in Petersburg, VA. It has excellent ratings online, with people saying they spent hours there. Though I’m starting to get a wee bit done with battlefields and related museums, we decided to check this one out due to the high ratings.

PHP is a private historical park. Honestly, it never even occurred to me that such a thing existed, and the cynic in me can’t help but wonder if there’s a private agenda to go with private ownership, though we detected none. The “driving force” behind the park is Dr. Robert B. Pamplin, Jr., who has eight degrees in business, economics, accounting, education and theology; among other things, he’s an ordained minister and the author of 53 books. To quote Hamilton, “Yo, who the F is this?!”

According to the information in their brochure, “Ulysses S. Grant and Robert E. Lee fought for control of Petersburg, key to the Confederate capital at Richmond. That contest ended on the morning of April 2, 1865 at what is now Pamplin Historical Park.

Grant’s decisive victory for the North was considered “The Breakthrough,” leading to the evacuation of Richmond and Petersburg that night.

Within the week, General Lee surrendered at Appomattox –– thus the park’s stance that the battle fought here led to the end of the Civil War.

There’s an assortment of things to do at the park.

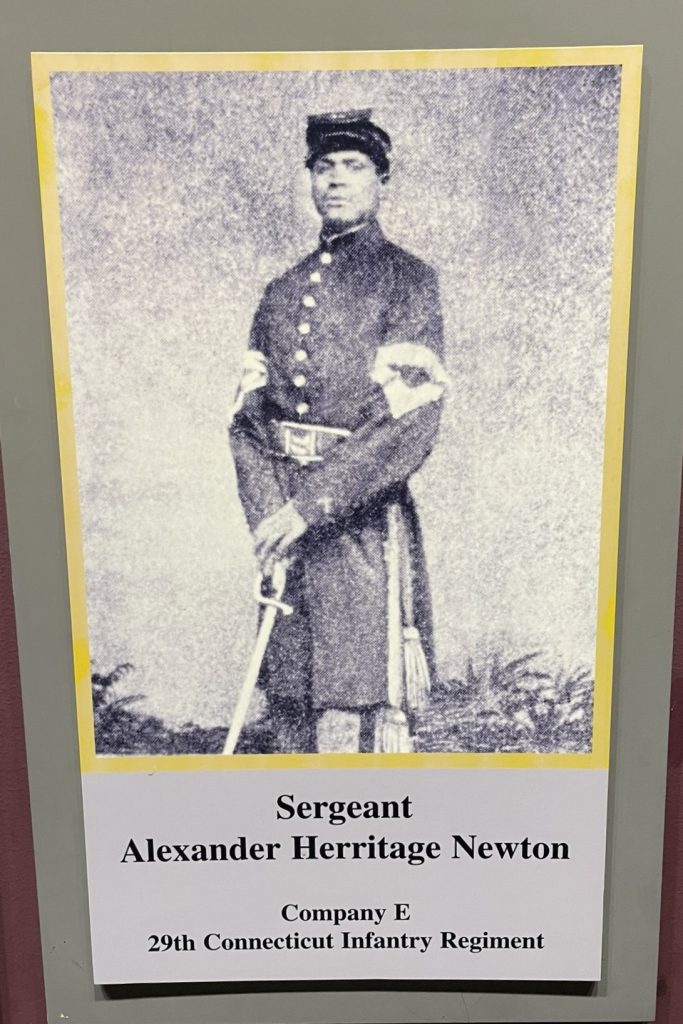

We started in the National Museum of the Civil War Soldier, which is done via an audio tour. When you enter, you pick a soldier from the wall and learn more about his specific experience during the war as you go through. My soldier was captured, escaped, and joined up with a new regiment!

The museum includes exhibits about the soldiers. What made them join? What was their daily life like? What did they wear, eat, carry? The museum was well-done, but roughly similar to other Civil War museums we’ve seen.

Also on the property is the Tudor Hall Plantation, which was constructed around 1812, but which is shown as it would have been at the close of the Civil War in 1865.

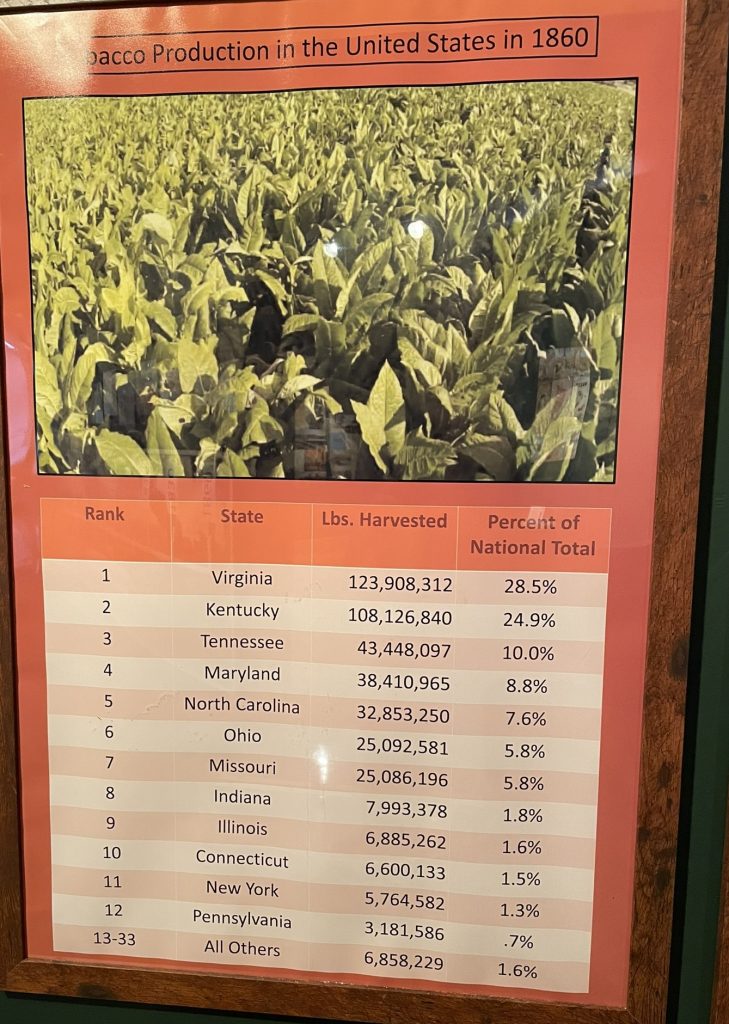

The plantation had grown tobacco, so of course was part of the economic system that only worked with enslaved labor.

Inside, half of the house was furnished as it was when it was occupied by officers in the Civil War, and the other half was furnished as it would have looked when the family was still living there. The furnishings inside, all “of the period” and not original, were not exceptionally exciting.

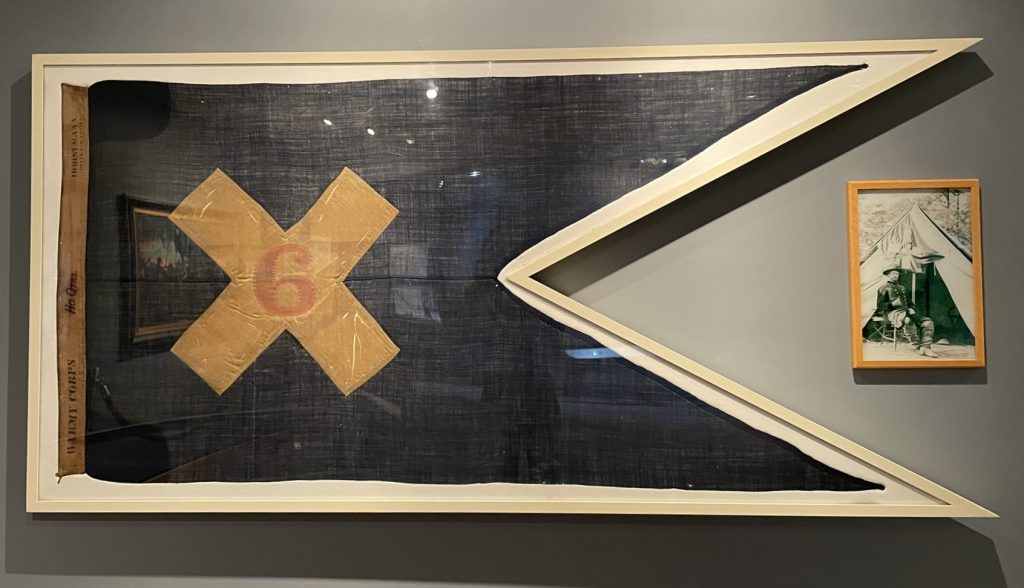

A second museum is housed in the Battlefield Center, featuring the exhibit Breaking the Backbone of the Rebellion, which focuses specifically on the battle at the park.

The park includes several miles of walking trails through the battlefield, including a large fortifications exhibit, and military encampments that are supposed to include interpreters recreating daily life, but which were quiet on a weekend afternoon.

A few miles away is the Banks House, which Grant used as his headquarters immediately following the victory. You can only see the outside, and it truly looked abandoned, though it has been used for staff housing.

More than four miles of trails snake through the battlefield where you can see the Confederate trenches. We did the 30-minute loop, which included winding our way over and around mounds of dirt that seemed to go on and on. Doug was a bit more impressed than I was, and remarked that being on the physical grounds of the battlefield provided a better understanding of what went on there.

In summary, die-hard Civil War buffs would probably get a lot more out of the visit that we did.