With our visit to Historic Tuckahoe in Richmond, Virginia, we knocked another difficult-to-visit, lesser-known presidential site off our list: the boyhood home of Thomas Jefferson.

Tuckahoe was built between 1730 and 1740 by the Randolph family, and amazingly, it’s not just the original home that is still standing, but many of the outbuildings, too, including original slave homes (a rarity, since they were often made of wood, which doesn’t stand up to time so well).

At its height, the plantation consisted of 25,000 acres, growing tobacco and wheat, and raising livestock. There were three mills on the property.

The Randolphs were close friends of the Jeffersons, and the patriarchs of each family promised that if anything should happen to one, the other would take care of the orphaned children. Sadly, this came to pass in 1745, after the untimely death of both Randolph parents.

Rather than bring the Randolph children to live at Shadwell, the Jefferson plantation, Peter Jefferson brought his family to Tuckahoe, with his wife and six children including two-year-old Thomas.

The Jeffersons stayed for seven years until 1752, caring for the children and managing the plantation. When young Thomas Mann Randolph, Sr., came of age at 11 years old (!), the Jeffersons returned to Shadwell.

Thomas was nine by this time, and had been receiving his early education in the one-room school house that still stands on the property today.

By 1830, Randolph family fortunes were in decline, and Tuckahoe was sold to another family to pay debts. Over the ensuing years, the home was sold several more times. The current family ownership began in 1935 when Isabel Ball Baker purchased the home, and today the home is the private residence of her grandson.

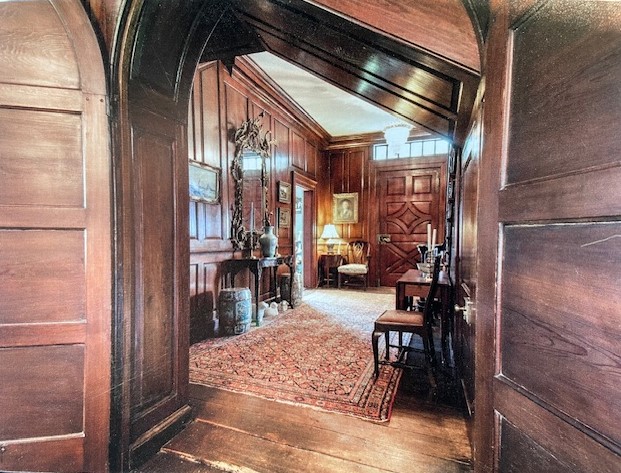

The home looks rather modest when viewed straight-on, but it is built in an H-shape that makes it quite large. Sadly, no pictures were allowed inside (below you’ll see us resorting to pictures of our postcards again), but it was beautiful, with wonderful wood paneling, carvings and moldings. The home is situated on a bluff over the James River.

Some Additional Fun Details about the Randolphs

(Doug couldn’t help himself and had to share the following tidbits about the family.)

Thomas Sr., the youngster who came of age at 11 and inherited the estate, would sadly see his wife die when he was 49. Wasting no time, however, he married a 17-year old beauty named Gabriella just a few months later. Gabriella was around the same age as the youngest of the 10 surviving children from Thomas Sr.’s first marriage, none of whom dealt very well with having a stepmother who was younger than they were. It is reported that none of the children returned to visit Tuckahoe after the new Mrs. Randolph took charge.

Thomas Sr. and Gabriella went on to have two children, a daughter who didn’t survive infancy and a son that they lovingly christened Thomas Mann Randolph after his father. But the thing is, Thomas’s oldest son from his first wife was already named Thomas Mann Randolph, Jr. The second Thomas Jr. later inherited Tuckahoe, not the oldest son.

The first Thomas Jr., would go on to be active politically and even serve as the 21st governor of Virginia. He married Thomas Jefferson’s third daughter, Martha, and was close to Jefferson for much of his life — until alcoholism, financial ruin, and anger management forced a separation. The couple reconciled before his death and he is buried in the cemetery at Monticello.

Even juicer, two of the daughters from the Randolph Sr.’s first marriage would go on to become embroiled in the Bizarre Plantation Scandal, named after the Antebellum tobacco plantation where Judith Randolph lived with her husband Richard Randolph (they were distant cousins). Judith’s attractive younger sister Ann had come to visit after the death of her fiance. Many months later, the Randolph couple and Ann were visiting nearby family when there was an scream in the night coming from Ann’s room. A servant told the lady of the house that laudanum had been requested, which was delivered, but nursing Ann in her delicate state was not sister Judith but brother-in-law Richard. He allowed no candles to be lit, and after a few minutes pushed the mistress of the house out the door. Judith remained in bed during the entire night.

In the morning, signs of something nefarious were discovered — blood spots on the stairs, a bloody pillowcase on the floor, Ann’s bedclothes nowhere to be found. The three Randolphs left at the end of the week, but the mystery only deepened when the corpse of an infant was found by enslaved persons in a pile of old shingles near the house. A sudden weight gain, acquisition of a compound that could have been used to abort a fetus, an affair with a married man, questions about a stillbirth and suggestions of outright infanticide — the case had all the hallmarks of a made-for-TV drama!

Local officials decided to prosecute Ann and Richard, and pressed the case all the way to trial for Richard. But thanks to the fact that enslaved persons were not permitted to testify in court, as well as Richard’s defense attorneys, a pair of middle-heavyweights named John Marshall (later Chief Justice of the Supreme Court) and Patrick Henry (of the “Give me liberty or give me death” speech), he was acquitted.

Fortunately for Richard, he would not have to endure much public censure from the scandal, but the manner of his escape was probably not to his liking — he died suddenly in 1796, three years after the trial. The unexpectedness of his death led to conjecture that Ann and Judith had something to do with his passing (though nothing was ever proven).

The shadow of scandal plagued Ann for many years. In 1807, she moved to Connecticut to serve as a housekeeper for peg-legged founding father Gouverneur Morris, but soon was promoted to the position of his wife. He was 57, she was 35.

Morris was intimately involved in the construction of the government of the United States. He signed the Articles of Confederation and the Constitution, and wrote the Constitution’s preamble. He also had a reputation as a lifelong bachelor involved in intimate activities of another sort, detailed in his personal diaries. His leg was amputated in 1780 after a “carriage accident,” but the scuttlebutt of the day was that he was injured while escaping an assignation when his lover’s husband appeared on the scene.

No stranger to scandal, Morris was unbothered by Ann’s reality-television-worthy past. The couple lived lavishly and were entertained by the Madisons at the White House. By all accounts their marriage was happy — at least until he died seven years after the wedding from internal injuries suffered after he tried to clear a blockage in his urinary tract by using a piece of whalebone as a catheter.

Ann and Gouverneur did have a son, Gouverneur Morris, Jr., for whom she was a dedicated mother. Of course, she did battle rumors about the boy’s paternity

Whoever said that history is boring is not looking in the right place!