We continued our exploration of Philadelphia for a second day. (Here’s what we did on our first day.)

Elfreth’s Alley dates to 1703, and currently has 32 small houses built between 1720 and 1836. Not surprisingly, it is in the Old City neighborhood of Philadelphia. It is named after 18th Century blacksmith and property owner Jeremiah Elfreth, who lived there with other tradesmen.

The street is cobblestone, and the houses are in the Georgian and Federal styles. There is a small museum with limited hours (so we did not get to go in) that works to “preserve and protect the Alley and tell the story of its inhabitants.”

The self-guided tour of the Philadelphia Mint was a bit of a dud because they were not manufacturing coins at the time of our visit. They can produce up to one million in 30 minutes, so seeing the machinery in full swing must be something!

The Philadelphia Mint was established in 1792, and was the first national mint in the country (as the city was then the nation’s capital). It has been at its current location since 1969. Exhibits show how coins are designed and made, including Congressional Medals, which it had not occurred to me the mint might produce. No pictures are allowed, which was a shame, because I really wanted pictures of the 1901 Tiffany mosaics depicting ancient Roman coin-making. Coinage coming from the Philadelphia Mint has a “P” or no designation as a throwback to the days when they were the only mint and so no mark was needed. Today mints also operate in Denver, West Point, and San Francisco.

This is the 1740 Betsy Ross House, where the famous flag-maker is purported to have lived when she sewed the first American flag in 1776. It was not known, in fact, exactly where she lived, but this house was selected and designated for preservation. As part of the restoration, the house next door was torn down to reduce the possibility of fire.

Later, subsequent research indicated that the razed building was where she actually likely lived. Oops! Doug and I had both previously visited the house, and so didn’t visit again.

The Christ Church Burial Ground opened in 1719, and is still an active cemetery today.

We wanted to pay our respects to Benjamin Franklin, who is buried here with his wife Deborah. Though the simple marker is for both of them and says 1790, that is the year Benjamin died; Deborah actually died 16 years earlier.

It’s a tradition to leave pennies on their grave as you can see in the photo.

Also buried in the cemetery are four other signers of the Declaration of Independence: Benjamin Rush, Francis Hopkinson, Joseph Hewes, and George Ross.

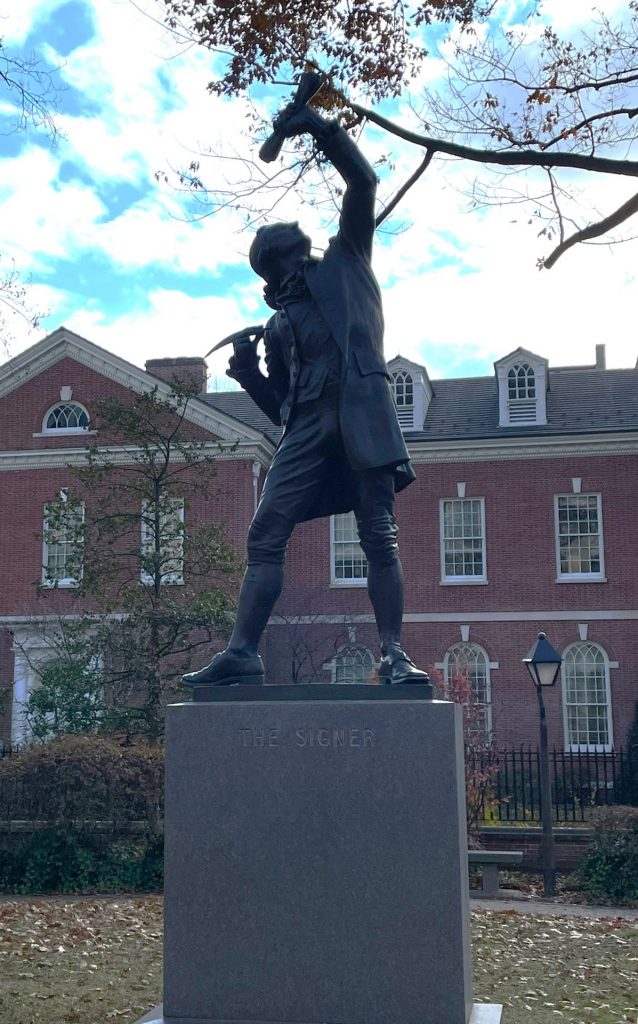

The Signer statue was created by EvAngelos W. Frudakis in 1980.

It is 9.5 feet tall (standing on a 6 foot base), and is modeled after George Clymer, who was a Philadelphia merchant who signed both the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution of the United States.

It is easy to forget that signing these documents required a great deal of courage (treason, anyone?), not to mention a huge financial risk should things not go as hoped.

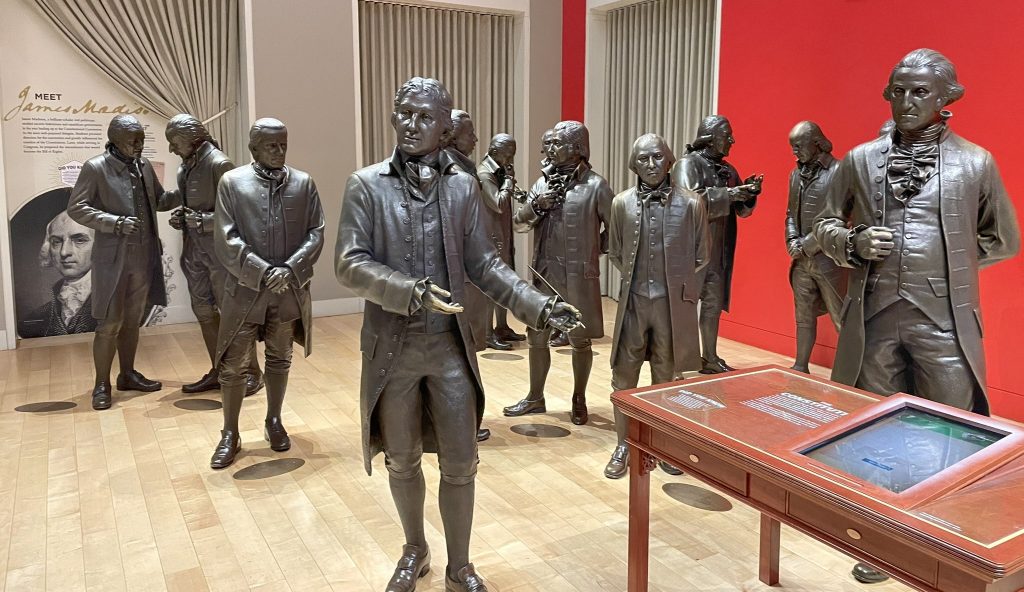

The National Constitution Center was better on paper than in reality. It is dedicated to the US Constitution (in a non-partisan way), and the exhibits include a lot — a lot — of reading. Now I love to read, but primarily while in my PJs at home. There just wasn’t much to see.

Signers’ Hall, pictured, allows you to walk amongst 42 life-sized bronze statues of the Founding Fathers, but unless you’ve been wondering how tall they were, it’s not exactly informative. I mean, it’s literally just a photo-op. Doug did enjoy talking with the volunteer docent on duty about Gouverneur Morris’s peg leg and James Madison’s short stature.

We also saw a dramatic one-man performance of Freedom Rising, which felt overly patriotic and completely out-of-touch with today’s political environment.

This printing block, circa 1820s-1830s, depicts a runaway slave, and was used by slave-owners who advertised a reward for the return of their “property”.

This was in the “Civil War & Reconstruction” exhibit, which was absolutely overrun by a high school students on a field trip who showed zero respect or interest for what was on display.

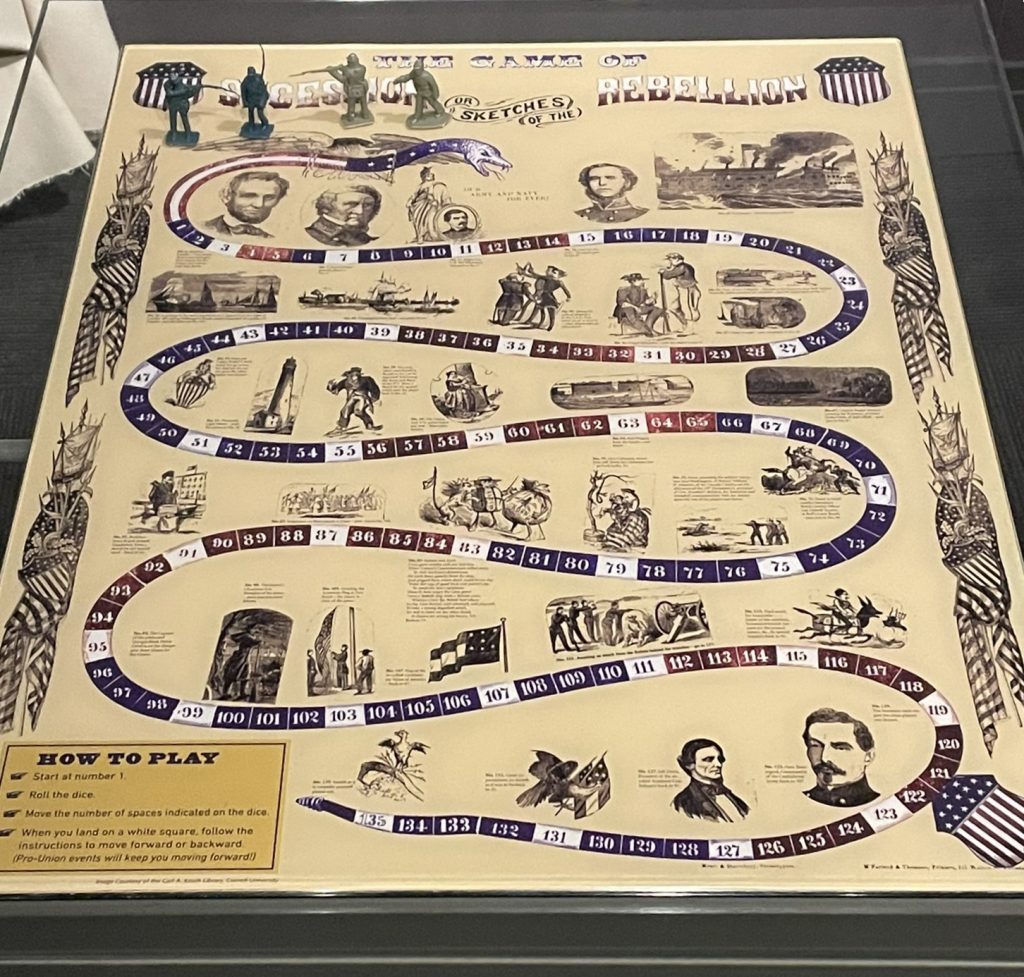

The Game of Secession was a board game produced in Philadelphia in 1862. Players advance through the board, stopping at people and events –– pro-Union was to your good, but Confederate stops would set you back.

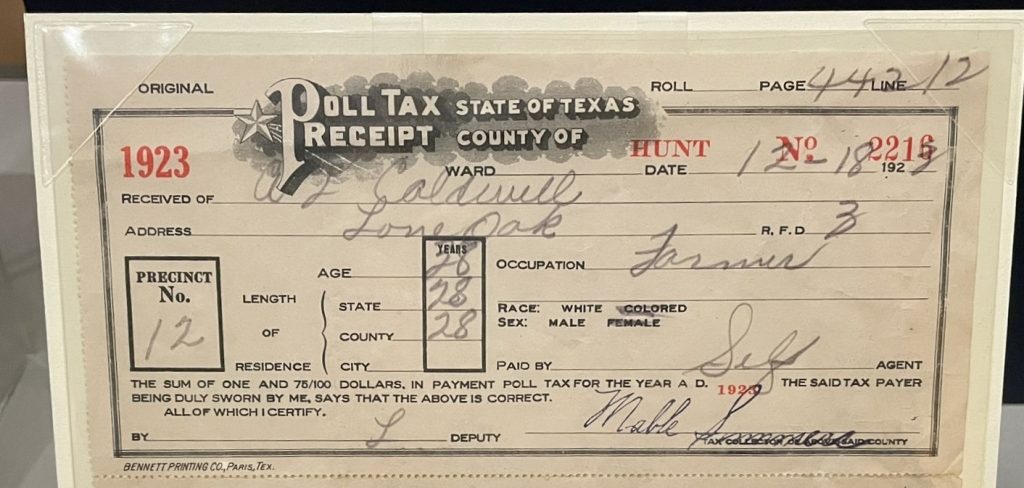

A Texas poll tax receipt from 1923. After the Fifteenth Amendment in 1870 granted African American men the right to vote, clearly something needed to be done to keep them from actually acting on their rights. Oh, there was the usual intimidation and threats of violence, but another way was through implementing poll taxes, which many black people could not afford. If you didn’t pay your poll tax, you couldn’t vote, which kept other riff-raff from voting, too! Easy peasy!

They weren’t outlawed until the 24th Amendment in 1964. 1964!

Independence Hall, in the Georgian style, was completed in 1753, and originally served as the Pennsylvania State House. The building was modified many times throughout the years, and the interior today is a mid-20th-century reconstruction of its 18th-century appearance. The steeple was the original home of the Liberty Bell (see our “One Day in Philadelphia” post). Independence Hall is pictured with an 1869 statue of George Washington by Joseph A. Bailly featured prominently out front; Independence Hall is also shown in the cover photo to this post.

Independence Hall was the primary meeting place of the Second Continental Congress, who debated and adopted United States Declaration of Independence here in 1776. Another big event happened here eleven years later, when the U.S. Constitution was ratified at the Constitutional Convention. Both of these events happened in Assembly Room, pictured. Shown in the back center is George Washington’s “Rising Sun Chair”, which you can also read about in our “One Day in Philadelphia” post.

The Vestibule in Independence Hall, with the Supreme Court Room visible on the left.

Tower Stair Hall in Independence Hall.

The Science History Institute is a small museum dedicated to “the history of the life sciences and biotechnology together with the history of the chemical sciences and engineering.” We were walking by when I remembered it was free, so we went in for a perusal. We spent a good bit of time exploring its exhibits.

After having toured several plantations in the south that referenced growing indigo, it was interesting to see this display on it. Indigo is a natural dye that’s been used for more than 6,000 years. Pictured is a sample of indigo-dyed cotton (2023) and 1860s containers of Barlow’s Indigo Blue dye; the glass container shows a sample of powdered indigo dye. Most Indigo dye today is synthetic.

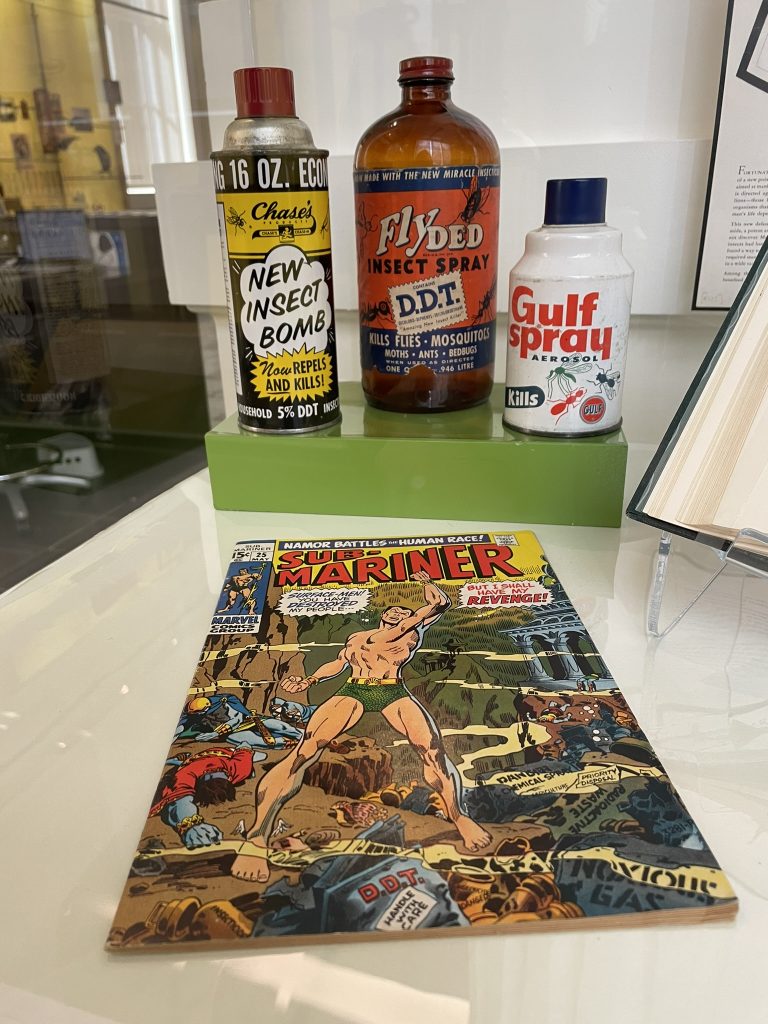

A Science History Institute display showing environmentally disastrous DDT products with a 1970 comic book on environmental concerns. The comic book features the superhero Namor surrounded by environmental pollutants.

Rachel Carson wrote about the harmful effects of DDT in her book Silent Spring in 1962.

This is a dye sample book showing the same material dyed different colors using acidic dyes. I can’t find the name of it or information on when it was published, but the German header at the top of the photographed page translates to “colors with acidic dyes”. The Science History Institute has a page on “Dye Sample Books on a Variety of Materials” that shows other such books. There’s something pleasing to the eye about it, I think!

The Episcopal Christ Church building dates to 1777 (though the congregation was founded in 1695). It saw many American Revolutionary leaders come through its doors, including Washington and 15 signers of the Declaration of Independence. Included in these is Ben Franklin, who is buried in one of the church’s cemeteries, located several blocks away (see earlier in this post!). In spite of its website and signs outside declaring it to be open, it was in fact, not.