Seeing that the Selma Interpretive Center (run by the National Park Service) was closed for renovations, I did not have a stop in Selma, Alabama, on our list for our current travels through the American South.

But a chance remark from a guide at another site in Alabama alerted me that the 59th anniversary of the Selma bridge march would be happening in just a few days, with people traveling from all over the state and beyond to pay tribute and commemorate the protests that were so important to effecting real change in the U.S.

These are exactly the kinds of experiences that we are looking for in our travels, so I scrambled to do some quick research and to get us to Selma on the day of the events.

In 1965 – 100 years after the Civil War had ended, mind you – voting rights for African-Americans in the South were in shambles.

“Legally,” everyone could vote. But in reality, poll taxes, impossible subjective literacy tests, intimidation, threats, and worse made it so that a Black person who wanted to register to vote generally had a very tough time of it – if they could register at all. Once registered, whether or not a person could actually cast their ballot was another matter.

To give you an idea of the kinds of tactics that were employed, here are some of the questions someone might have to answer when trying to register to vote. The answers were subjectively judged by the registrar who could easily like a white person’s answers, but not a Black person’s:

- How many seeds are in a watermelon?

- How many bubbles are in a bar of soap?

- How many jelly beans are in the jar in front of you?

In Dallas County (where Selma is located), there were 15,000 voting-age African Americans in 1961, but only 156 of them were registered to vote. When African-Americans showed up to register at the county courthouse, Sheriff Jim Clark and his deputies harassed and attacked them.

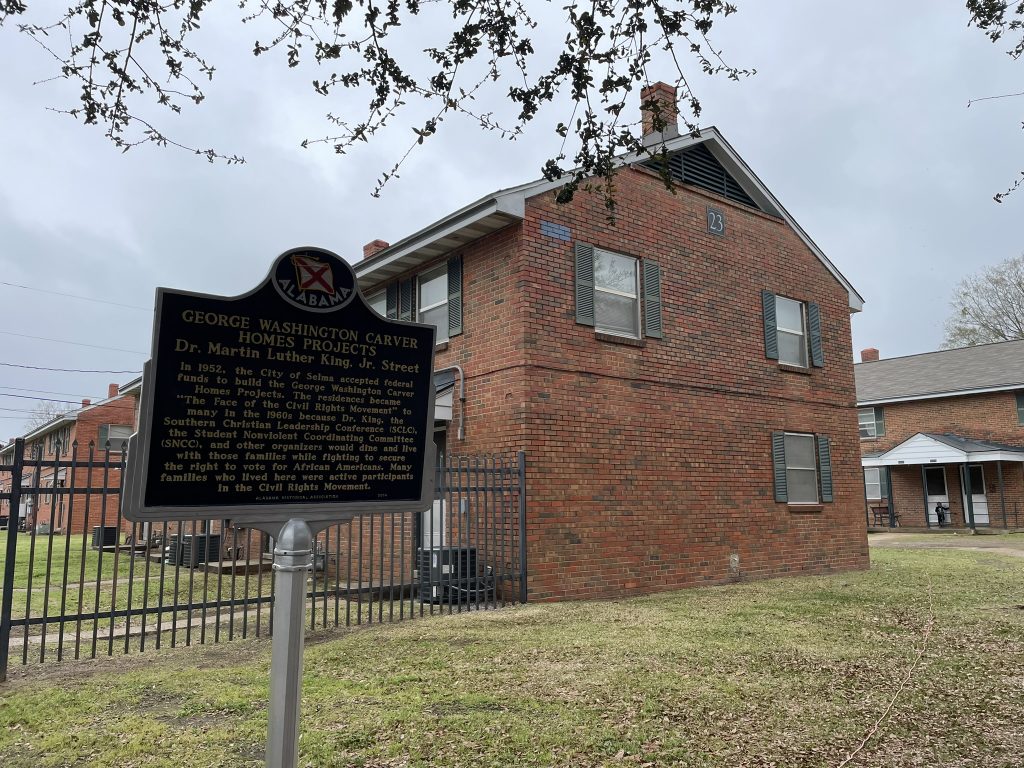

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., the head of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, hoped that Clark’s behavior would draw national attention. In January 1965, marches began in earnest on the short route from local churches to the courthouse, aiming to pressure local officials to allow the marchers to register to vote. Not surprisingly, the marchers were met at the courthouse with rough handling and arrests, indeed, putting a national spotlight on Selma. In February, Dr. King was arrested in a march along with 3,000 others, with the police using nightsticks and cattle prods on the marchers.

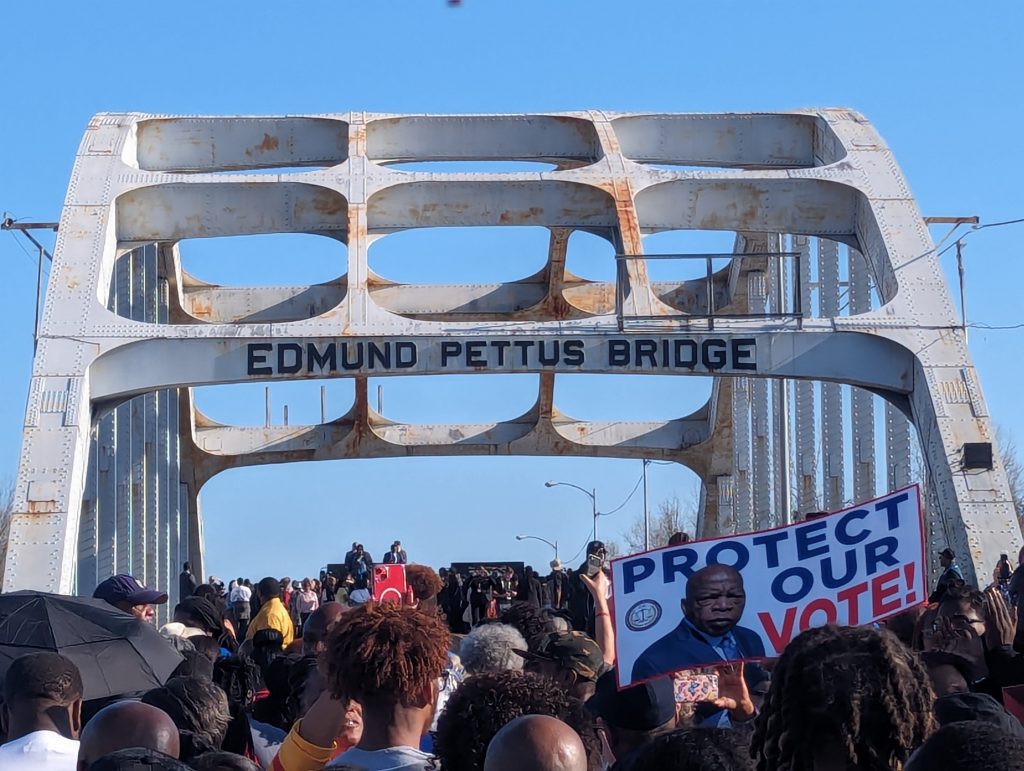

During another march, a young demonstrator was fatally shot. The focus then shifted from marching to the courthouse to marching 54 miles from Selma to the Alabama Capitol in Montgomery. On Sunday, March 7, 1965, 600 marchers left the Brown Chapel AME Church and marched the few blocks towards the Edmund Pettus Bridge (named after a Confederate brigadier general and state-level leader of the Alabama Ku Klux Klan).

As they reached the crest of the bridge, they saw what future Congressman John Lewis described as a “sea of blue” – Alabama state troopers blocking the way. The marchers asked to be allowed to pass, but they were told they had two minutes to turn back. While the marchers kneeled to pray, the troopers viciously attacked with nightsticks, whips and rubber tubes, and released tear gas. Violent images were broadcast around the nation, and the day thereafter known as “Bloody Sunday.”

More marches followed, along with more violence. But finally, on March 21, marchers set out from Selma and made it to the capital. As they approached Montgomery, their numbers swelled to 25,000 protesters. On August 6th President Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act into law.

Worried about parking our oversized van, we arrived in Selma early in the day of the commemorative events. We walked around Selma to see some of the historic sites and peruse the vendors at the street fair. Vice-President Kamala Harris was expected for the event, so security was tight. The afternoon mostly involved hours of waiting around – to get through security, for speeches to start, for speeches to end, for Kamala’s photo-ops to finish, for the VIPs to do their own march over the bridge.

Finally, we commoners were released, and the crowd surged ahead, the atmosphere jubilant. The people in attendance were of all colors and from all walks of life. Many carried signs or wore shirts that expressed their convictions, and images of John Lewis were everywhere. As we reached the crest of the bridge, we took a moment to remember how terrifying it must have been 59 years ago to see what was waiting on the other side.

In conjunction with this visit I am currently reading Selma’s Bloody Sunday (affiliate link) by Robert A. Pratt, which of course gives much more context and in-depth review of what happened than this post. It’s truly horrifying.