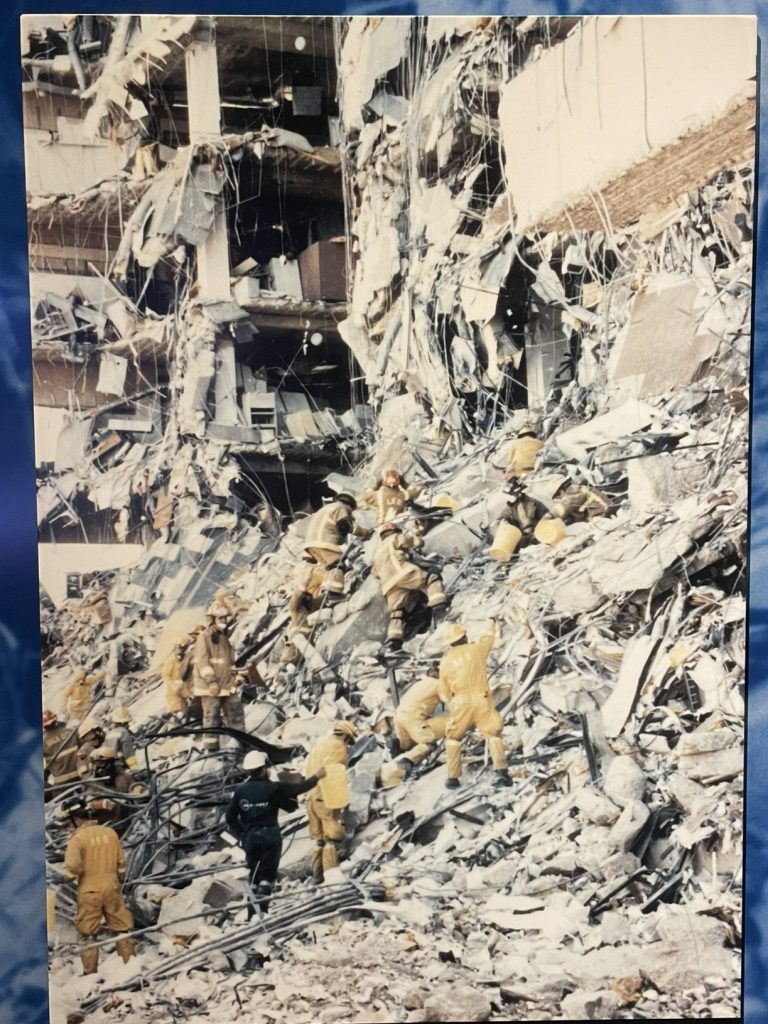

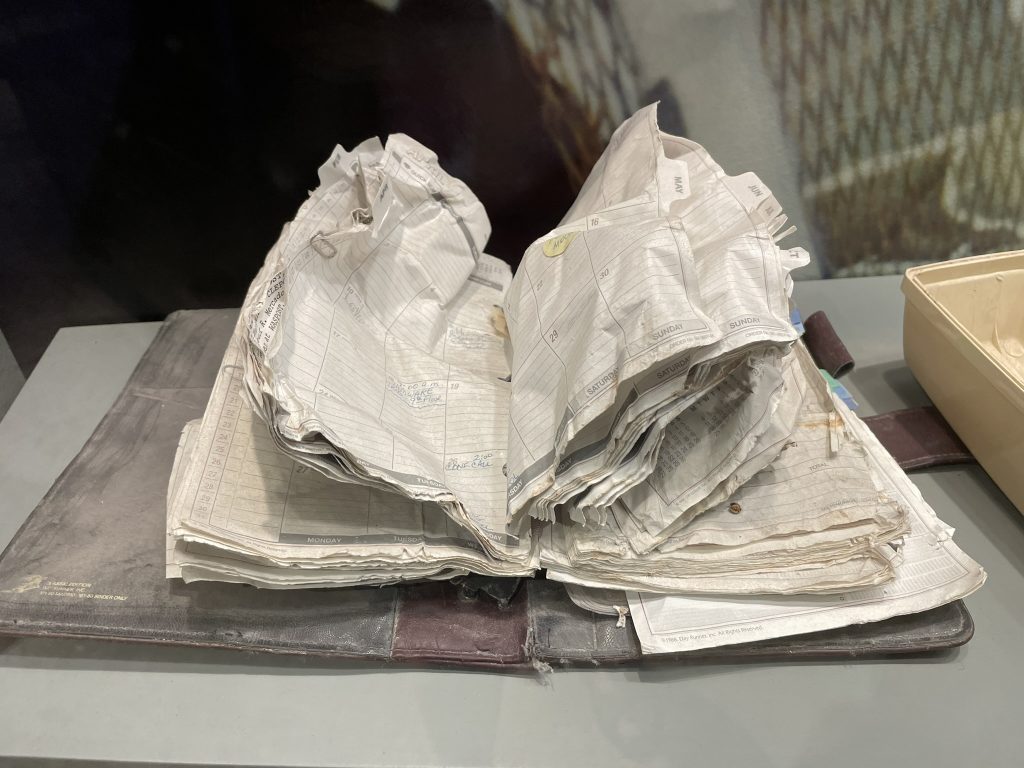

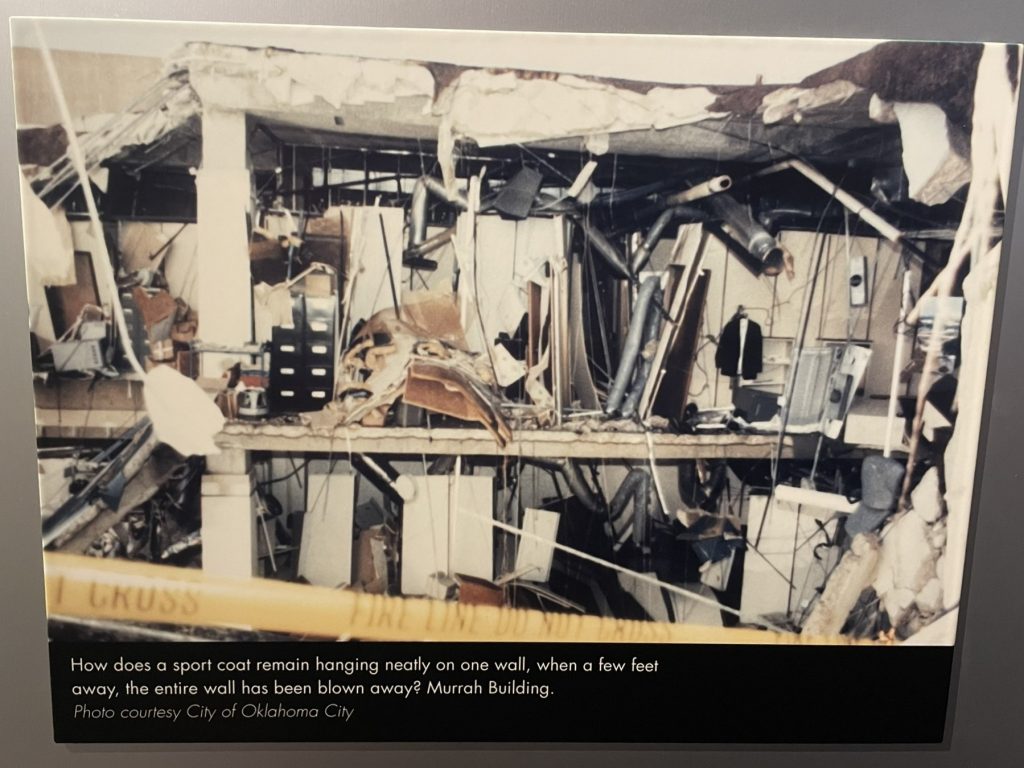

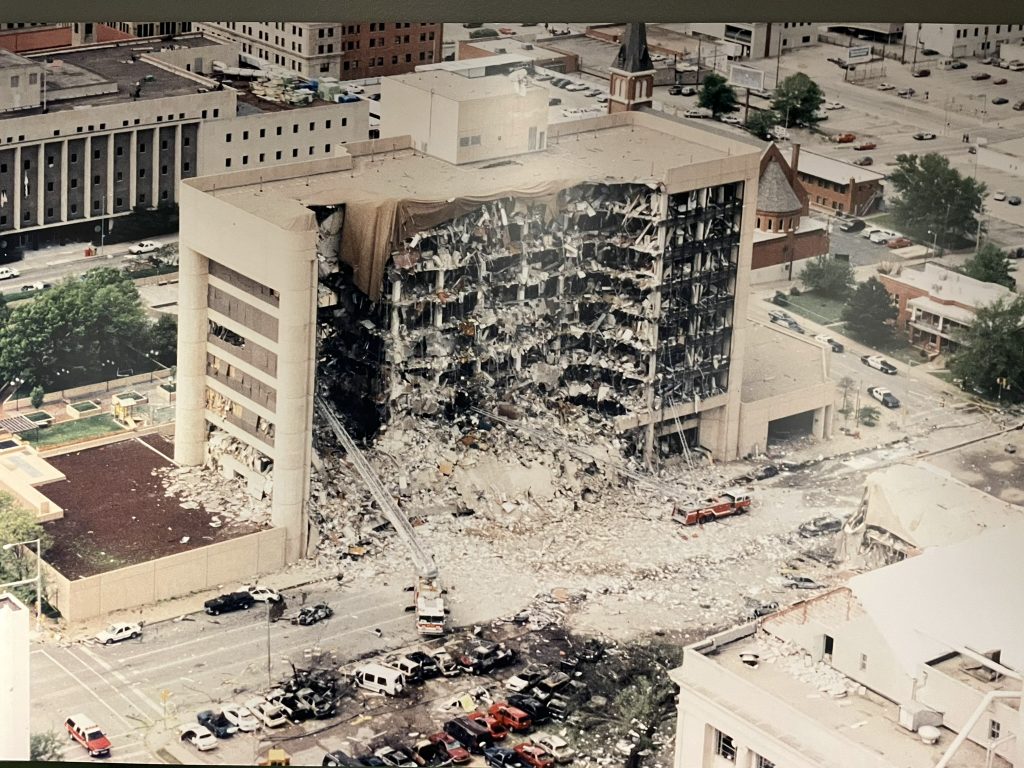

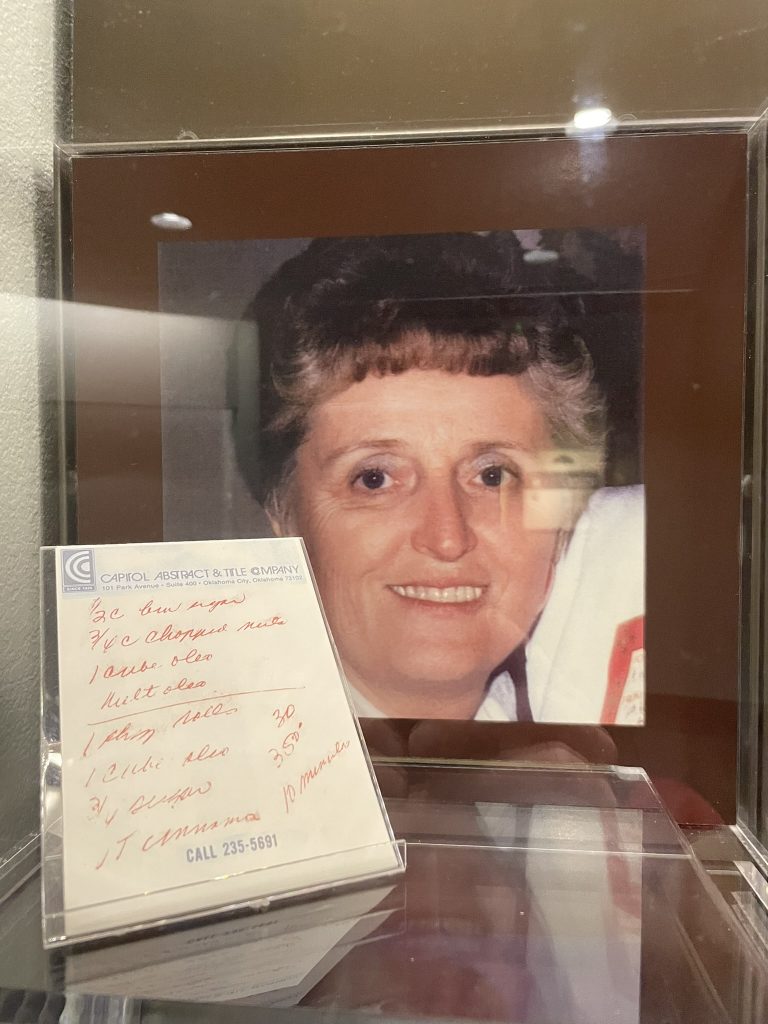

It’s been almost 30 years since Timothy McVeigh detonated a bomb outside the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, killing 168 people and injuring 680. More than 1/3 of the building was destroyed, and 324 buildings in the vicinity were also destroyed or damaged (mostly shattered glass). It is one of the deadliest acts of domestic terrorism in U.S. history, and the Oklahoma City National Memorial & Museum tells the story.

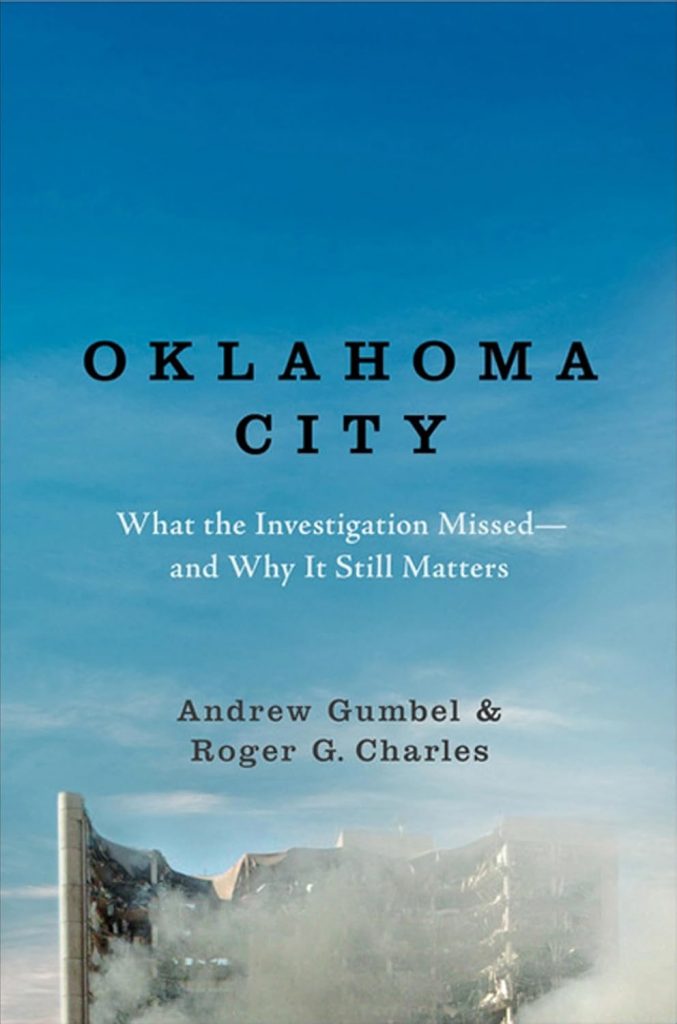

The plot was carried out by Timothy McVeigh and Terry Nichols, though McVeigh seems to be the ringleader in the version of the story told by the museum. I had listened to Oklahoma City: What the Investigation Missed–and Why It Still Matters by Andrew Gumbel before going to the museum, and that book makes a strong case that others were involved. However, there is no hint of that in the museum.

McVeigh, a Gulf War veteran, became increasingly disgruntled and anti-government. The events at Ruby Ridge in 1992 and at Waco in 1993 seemed to have pushed him to the brink. He developed a plan to blow up the federal building, using Nichols, a friend he met in the U.S. Army, to obtain and finance supplies. Nichols really just comes across as a buffoon who can’t say no to McVeigh, as opposed to someone with genuine interest in the plot itself.

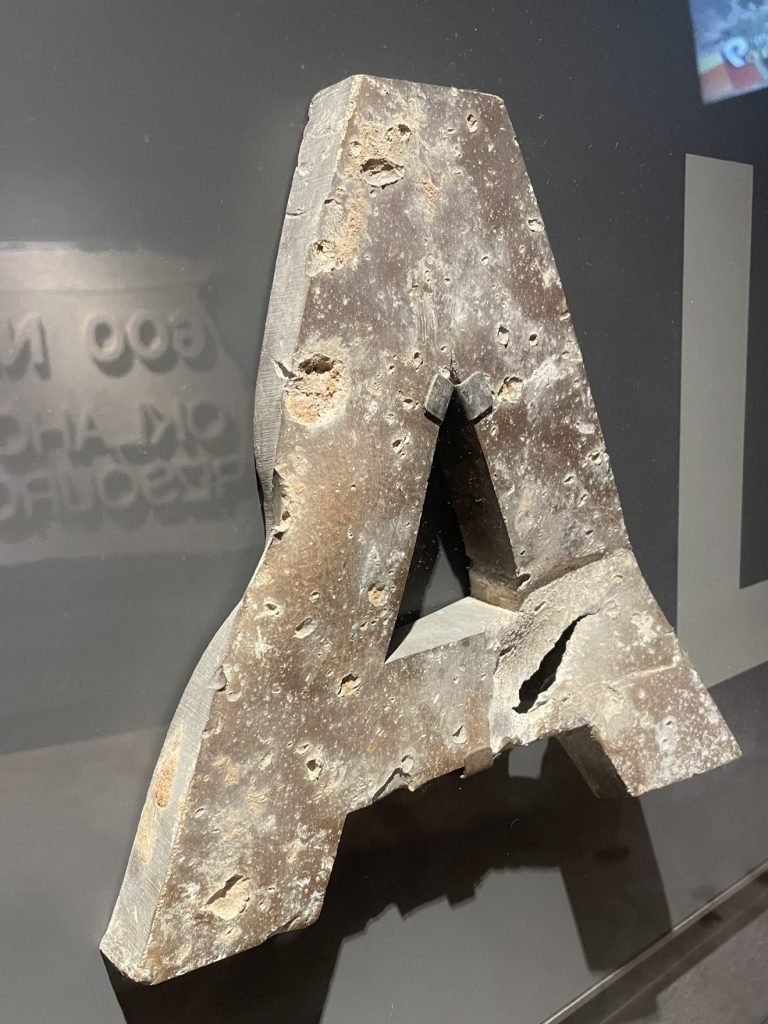

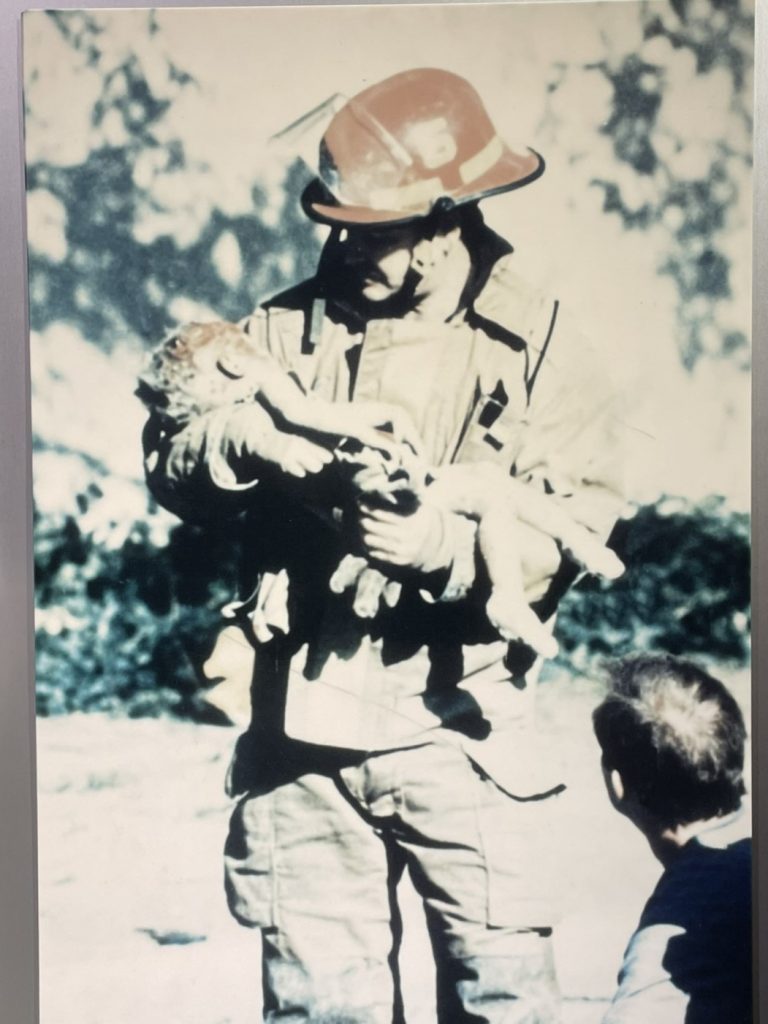

McVeigh carried out his attack on the second anniversary of the Waco siege, on April 19, 1995. The federal building was chosen for a few logistical reasons, but also because it housed 14 federal agencies. The bomb was a Ryder rental truck packed with 4,800 pounds of ammonium nitrate fertilizer, nitromethane, and diesel fuel mixture. 168 people were killed, including, horrifically, 19 children, due to a day care center located in the building, which McVeigh knew about but didn’t care.

By sheer luck for the detectives and sheer stupidity for McVeigh, he was stopped by the police just 90 minutes after the bombing for driving without a license plate, whereupon he was arrested for illegal weapons possession. He was held for just enough time for officials to piece together that he was their man, and within days Nichols was rounded up, too.

McVeigh was convicted in 1997, and executed in 2001. Nichols had a federal trial, for which he was sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole, and a state trial, for which he received 161 consecutive life terms without the possibility of parole. Another man, Michael Fortier, received 12 years for his foreknowledge of the bombing plans.

The museum and memorial are located on the site where the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building had stood. The memorial includes a reflecting pool with large gates on either end; one is inscribed with the time 9:01, the other with 9:03. These represent “before” and “after”, as the blast occurred at 9:02.

Alongside the pool is a “Field of Empty Chairs”, with each person killed represented by a chair with their name etched on it. The small chairs represent child victims.

The cover photo is the Survivor’s Tree, an American Elm that survived the bombing.