The Harriet Beecher Stowe House

The Harriet Beecher Stowe House was not the most visually exciting of our stops, especially since they had just refinished the inside but were still waiting for the furniture to arrive. This made for a lot of empty rooms with garish wallpaper (as was popular at the time).

We had previously visited the home where Stowe lived the last 23 years of her life in Hartford, Connecticut. That home is full of things connected to Stowe, so a lot more interesting in terms of things to look at. I will say the tour guide for this home in Cincinnati was super enthusiastic and did her best with what she had to work with.

Stowe’s family moved to Cincinnati in 1832 when she was just 21 years old (and also still just Harriet Beecher). Her father, a renowned minister, had accepted a job as president of Lane Seminary just up the street. Many Cincinnatians were active in the abolitionist movement given its location just across the river from pro-slavery state Kentucky.

Stowe began her writing career while living in Cincinnati. She also traveled to Kentucky where she witnessed the slave auction that would be featured prominently in her 1852 novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin, which she wrote shortly after leaving Cincinnati.

The 5,000-square-foot home was completed in 1833 as a home for the president of Lane Seminary. Stowe lived there with her family, and for a short while after she married in 1836. Her first two children, twin girls, were born in the home, as well.

Stowe’s father led the seminary for 20 years, remaining in the home with his family. After that, the home passed into various hands, eventually becoming a tavern and inn. It required massive renovation to restore it to the Stowe’s time period.

The cover photo to this post features early editions and global translations of Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

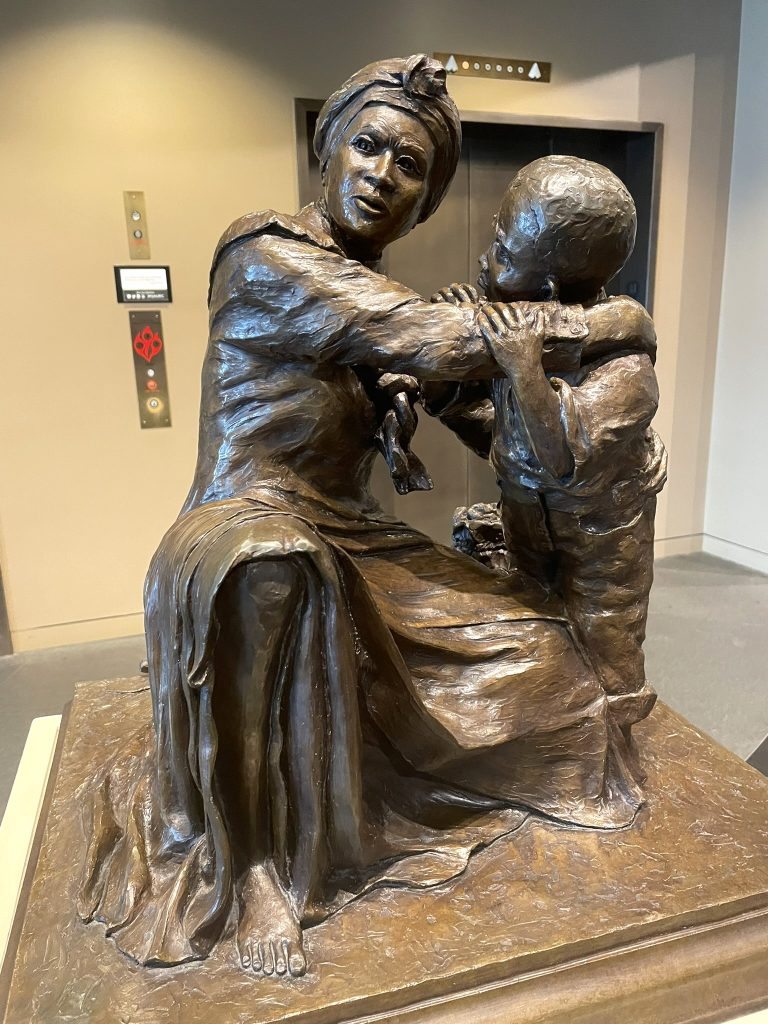

National Underground Railroad Freedom Center

The National Underground Railroad Freedom Center turned out to be an underwhelming experience for us, in spite of being a highly-rated museum.

Before going I saw on this notice on their website: “Portions of the museum will be inaccessible as we replace our flooring.” To me, “portions” indicated a room or two might be closed, so we still went.

As it turned out, the entire second floor was closed, and since the museum’s main exhibits are on the second and third floor, this turned out to be a significant “portion.”

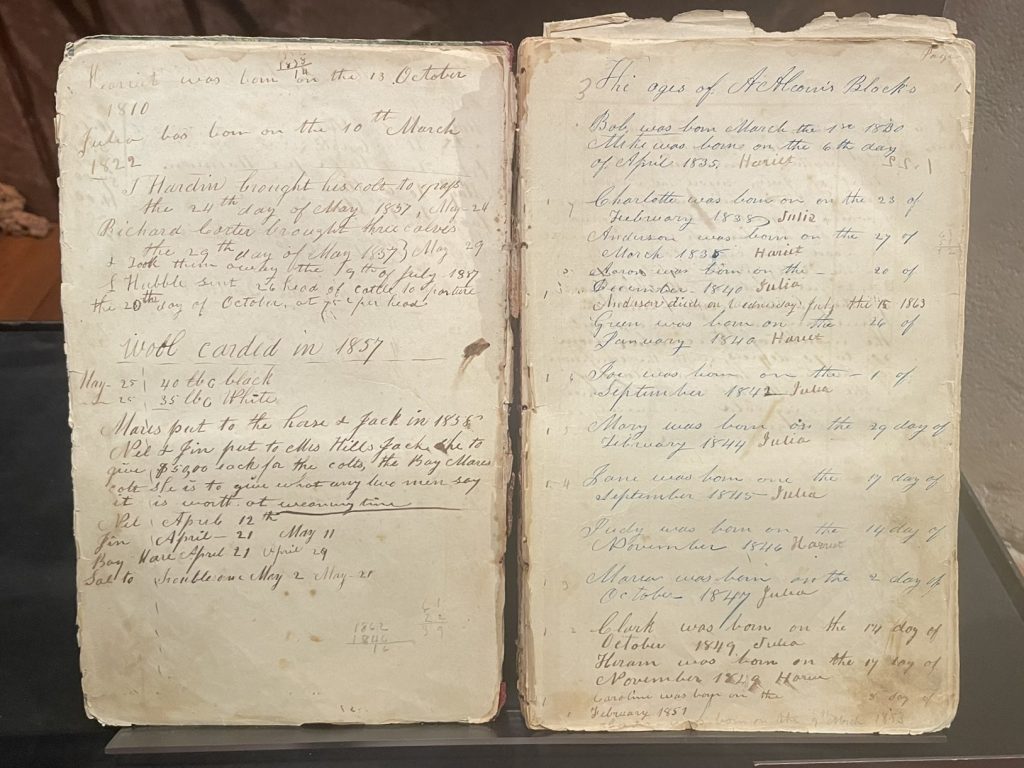

Even worse (for us), the exhibits on the third floor were on slavery in general, which we have had extensive coverage of in the Civil Rights museums we’ve already visited. So the portion of the museum that was actually about the Underground Railroad that we were there to learn more about was 100% off limits. It also turns out that the second floor is where the museum’s most prized artifact is: an 1800s “slave pen” relocated from Kentucky

Needless to say, it did not take us very long to get through the museum, and I’m pretty much feeling like we will need to go again to consider it truly visited. We did get to watch the film Brothers of the Borderland, which “immerses guests in a thrilling flight to freedom, showcasing the courage and cooperation of John Parker and Rev. John Rankin as they aid a woman risking everything to flee slavery.”

The museum opened in 2004, and it is located on the Ohio River, which was a dividing line between free-state Ohio and slave-state Kentucky. Many enslaved people found refuge in Cincinnati after crossing the river, though they were not safe in the city, as slave-hunters were numerous and it was illegal to help runaway slaves.