Doug and I made time to visit the Atlanta History Center (AHC) since there were four exhibits that we wanted to see, one of which was temporary and so we wanted to make sure we saw it while we were in Georgia.

The AHC was founded in 1926. It is situated on 22 acres and features historic gardens and buildings on its grounds. The Center also manages the Margaret Mitchell House at another location, which was unfortunately closed for renovations while we were there. It quickly became clear we hadn’t allotted enough time to take everything in, one could easily spend several hours here.

The first exhibit we were interested in was Atlanta ’96: Shaping an Olympic and Paralympic City. On our drive towards Atlanta we listened to The Suspect: An Olympic Bombing, the FBI, the Media, and Richard Jewell, the Man Caught in the Middle by Kent Alexander.

The book covered how the Olympics came to Atlanta, in addition to the very sad case of Jewell being falsely accused in the media of being the bomber. Unfortunately, we were both underwhelmed by the exhibit.

Cyclorama: The Big Picture was the next exhibit on our interest list. It features the 132-year-old hand-painted cyclorama painting of The Battle of Atlanta. It stands 49 feet tall and is longer than a football field. In its current configuration it can be viewed from two levels.

Interestingly, it was originally painted in 1886 as an accurate portrayal of the 1864 battle, but when it arrived in Atlanta on tour in 1892, it was modified in parts to make it appear to represent a Confederate victory! Most of these changes were reversed in the 1930s.

The Cyclorama is one of only two in the United States; the other is in Gettysburg, which we have also seen. I told Doug to make a list for U.S. Civil War cycloramas so we can mark it complete.

Turning Point: The American Civil War was the next permanent exhibit we were interested in. The museum holds one of the largest collections of Civil War artifacts in the U.S. The exhibit walks through the timeline of the war through the eyes of soldiers and civilians. The museum claims the Atlanta Campaign of 1864 was a turning point of the war, and that the surrender of the city in conjunction with the re-election of President Lincoln was what ultimately led to the freedom of 4 million slaves. It seems to me, though, that every site makes the claim that they were the “turning point” of the war. This was another one of those exhibits where it was clear a lot of work and effort went into the presentation, but it didn’t really do much for me. Doug was more impressed with the collection.

The final exhibit, however, knocked me for a loop. This was the temporary exhibit Emmett Till & Mamie Till-Mobley: Let the World See, which is on display through September 17, 2023. It was powerful and overwhelming, and I sobbed hard.

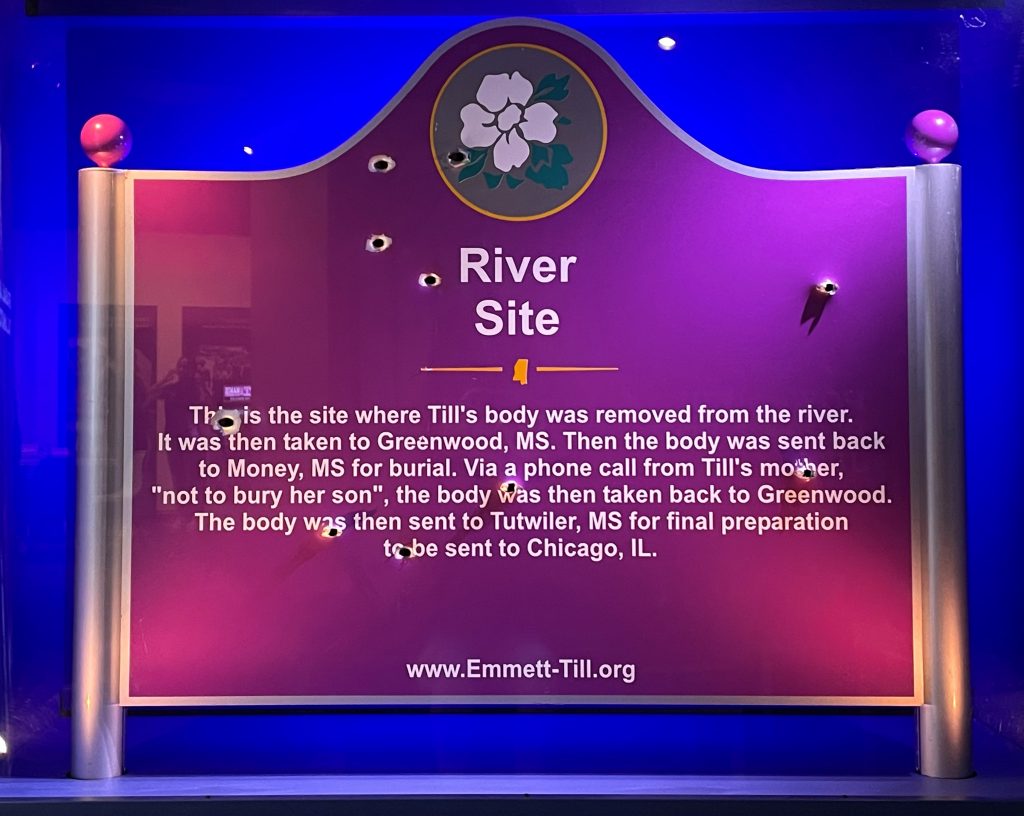

Emmett Till is of course the 14-year-old Chicago boy who was lynched for allegedly whistling at a white woman while visiting cousins in Mississippi in 1955. He was tortured by his captures and his lifeless body was thrown in the river, discovered by fisherman three days later.

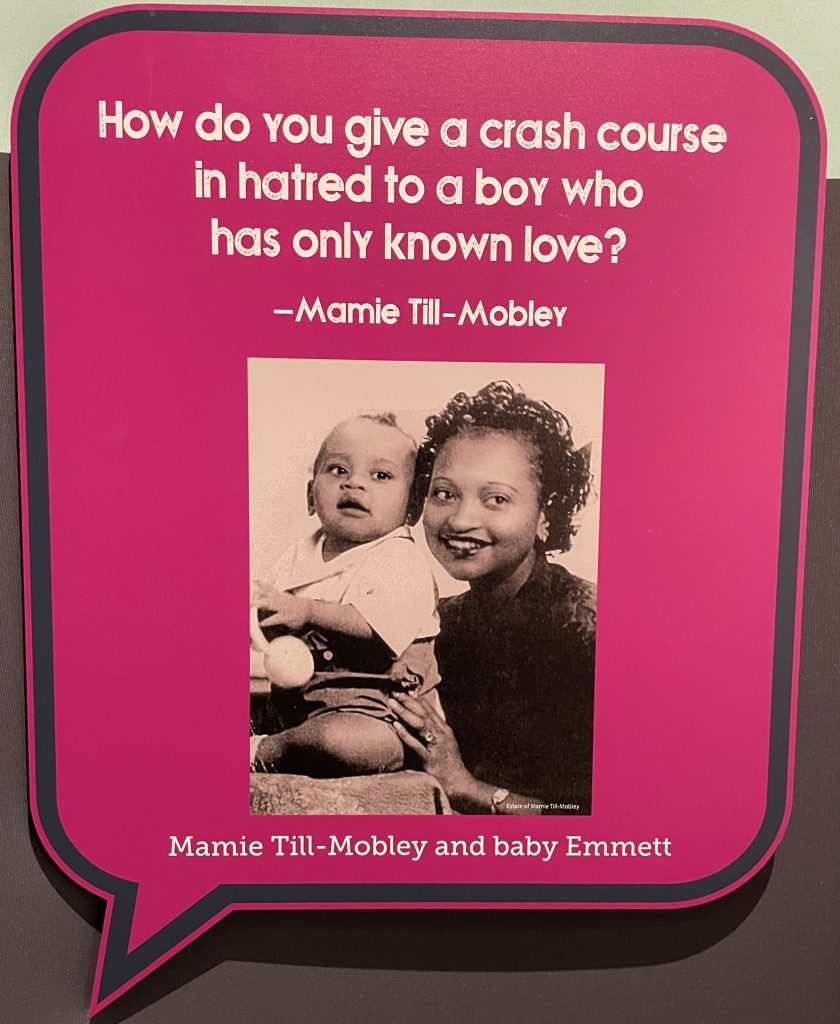

When his mother Mamie Till-Mobley saw the battered body, she called in a photographer and had the images sent to newspapers (though only black papers published them), saying “Let the world see what they did to my boy.” The exhibit had one of the images on view (marked with a warning sign), and I hesitated before reaching for it, deciding it was my civic duty to look. I gasped out loud and the tears I’d been holding back were unleashed.

There was also a video about how a memorial sign marking the spot where Emmett’s body had been recovered has been repeatedly shot at, and repeatedly replaced over the years. I’m sure it goes without saying that Emmett’s murderers got off scotch-free.

Before we’d even left the parking lot, we had downloaded The Blood of Emmett Till by Timothy B. Tyson. The book told Emmett’s story, of course, but also put it in horrifying context to life in the South at the time.

It was a hard listen, to be sure; I liked the author’s description of “not sufficient but meaningful” change that Mamie’s actions inspired. I can’t help but admire her ability to channel her anger into action during a time of indescribable grief.

There are several other permanent exhibits that would capture others’ interest, in addition to the outbuildings and gardens, which we ran out of time for.

2 thoughts on “Atlanta History Center”