Doug grew up near Gettysburg and still has family there; in spite of many visits over the years, I still hadn’t managed to do a proper tour of the battlefield at Gettysburg National Military Park.

Since I normally do all of the driving, a self-guided driving tour of something is generally not much fun for me, so this time I decided to spring for a bus tour so I could actually enjoy it. As it happened, it rained during the entire tour, so the windows were foggy and covered in rain drops and we hardly got off the bus.

The bus also drove up and around many of the monuments and didn’t even pause for us to take a picture (not that we really could have anyway). And our guide seemed more focused on making jokes than giving us a proper understanding of what happened.

Therefore, the following weekend found us back at the park, armed with a list of “best monuments at Gettysburg” and the National Park Service app queued up with the auto tour.

This time the weather was spectacular, and the fall colors were just starting to pop.

I had prepared for this by watching the movie Gettysburg, which was filmed on location, and I do feel like that helped a lot.

The auto tour and signboards at the stops helped bring it all together as best as can be hoped for 160 years after the fact.

The park covers about 5,000 acres, less than half the actual area of the battlefield.

The battle lasted three days, and the 24-mile auto tour had 16 stops. Needless to say, the drive took that better part of an afternoon, with Doug at the wheel so I could properly take in the sights.

We had previously visited the museum at the visitors’ center, so did not feel the need to re-visit it.

The Battle of Gettysburg is often referred to as the “High Water Mark” of the Civil War. The war had been raging for two years by this point, but the North had yet to win anything of significance.

The costly win at Gettysburg, along with the near-simultaneous win at Vicksburg, helped Lincoln get re-elected, and gave the North the boost it needed to fight on.

Though the war dragged on another two years, the Battle of Gettysburg is considered by many historians to be the turning point of the war.

The battle began on July 1, 1863 and culminated on July 3 with now infamous “Pickett’s Charge”, when 12,000 confederates charged across a mile-wide open field towards Cemetery Ridge.

In less than an hour, 5,000 of them would be casualties.

With around 50,000 total casualties over three days, out of a total 175,000 troops from both sides assembled there, it is still the costliest battle in US history.

Due to the high number of deaths, it soon became clear a new cemetery was needed. Local leaders rallied and the Cemetery was established later that same year in 1863.

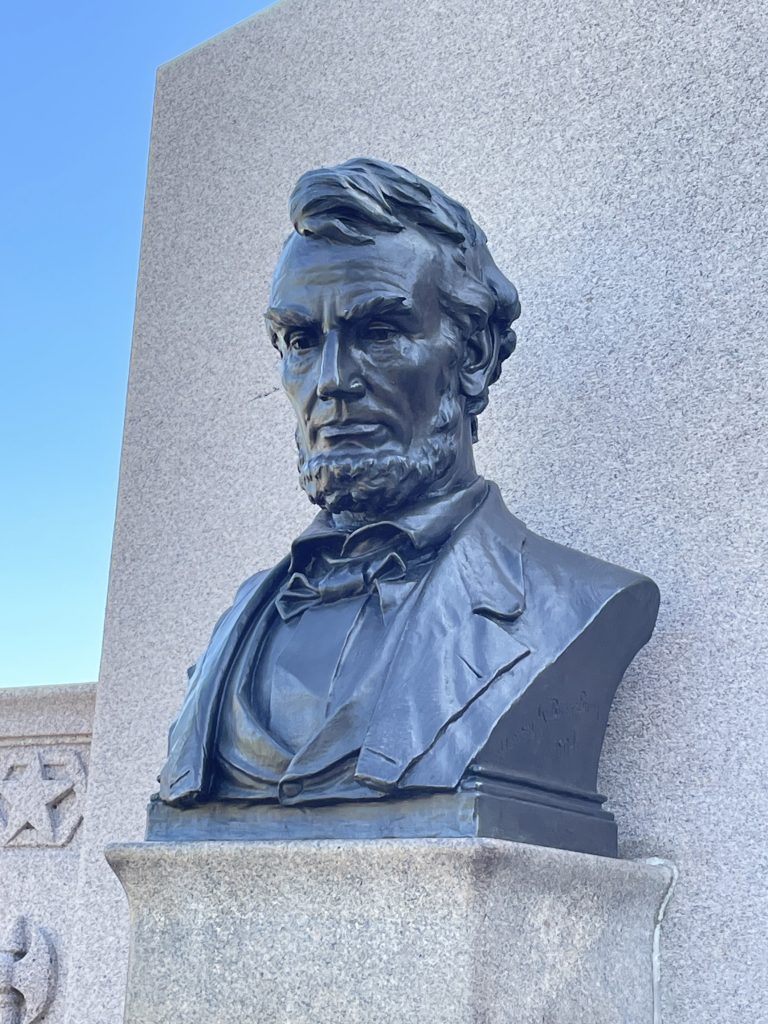

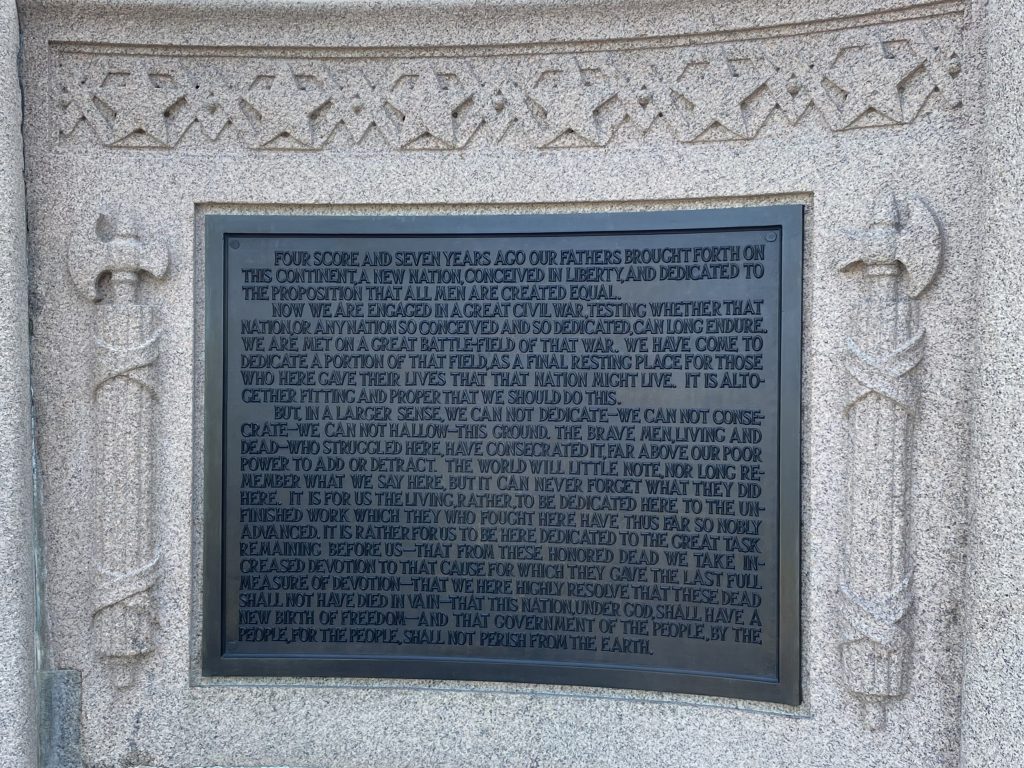

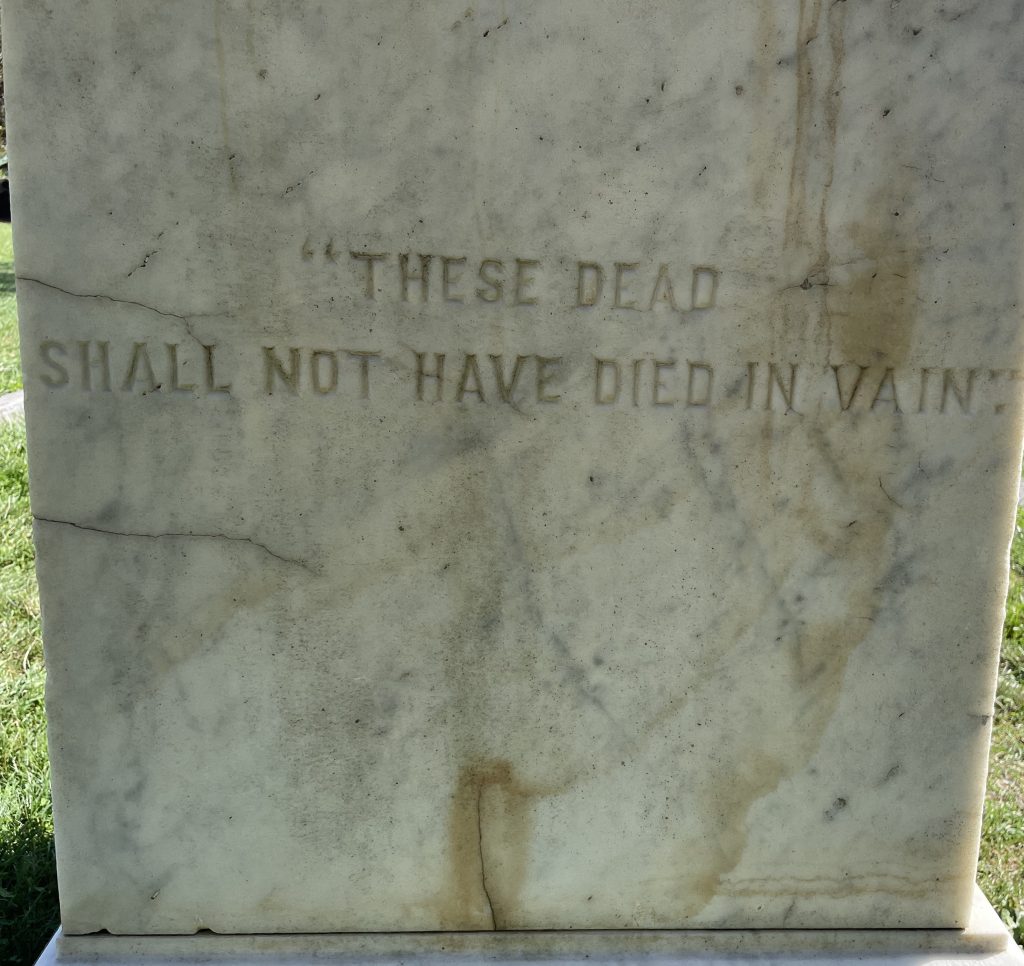

The Gettysburg National Cemetery was created, and the Union fallen were interred here. At the Cemetery’s dedication ceremony just a few months after the battle, Abraham Lincoln was invited as an afterthought to give “a few appropriate remarks.” The two-minute speech he gave became known as his “Gettysburg Address.”

As the war was still ongoing at this point, Confederate soldiers were not buried here; the majority were sent to Hollywood Cemetery in Richmond, Virginia (which we visited earlier in the year).

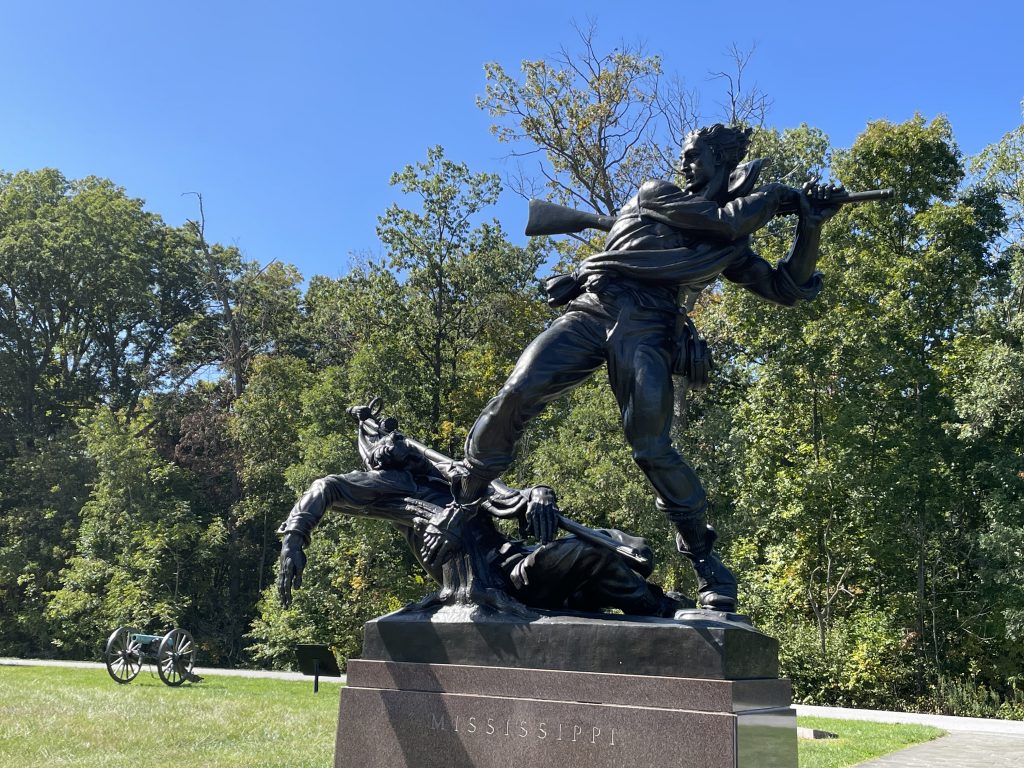

There are 1,328 monuments in Gettysburg National Military Park. Many are absolutely amazing, though they seemed to be everywhere and I am honestly surprised the real number isn’t twice that much.

Roughly one-quarter of these are monuments to Confederate soldiers or states. On the National Parks Service website there is a “Confederate Monuments Statement”, which reads, in part, “Unless directed by legislation, it is the policy of the National Park Service that these works and their inscriptions will not be altered, relocated, obscured, or removed, even when they are deemed inaccurate or incompatible with prevailing present-day values.”

Just as we arrived at the enormous Virginia monument, featuring General Robert E. Lee atop his horse, a passing cyclist yelled out “Traitor! Traitor!”

This led Doug and I to debate discuss the definition of “treason,” whether it’s appropriate for Lee to have this statue here in the park, and what it means to visit it.

I’ll just say that it is interesting to think about your values and ideals today, and wonder if in 100 years you will have turned out to be on the wrong side of history.

The Virginia Monument is positioned very near where Lee watched the massacre of Pickett’s Charge unfold in front of him in 1863.

While one can get a good feel for the landscape of 1863, the park does have more woodlands today than it did back in 1863. The National Park Service is working to restore the battlefields to their 1863 conditions, including restoring native plants and replanting historic orchards.

I visited Gettysburg with my parents twice, once when I was ~10, then ~13. My father was a Civil War buff. My mom seemed disinterested and unenthusiastic. We drove the roads several times over so my dad, battle map in hand, could associate places with seminal moments in the battle. As a middle schooler, I loved history but the expanse and meaning of the actual battlefield was lost on me. It wasn’t until we visited Gettysburg Diorama that I “got” it.

Extant monuments dedicated to the “other side” whether they be the Confederacy, Columbus or plantations where slavery took place may always be divisive, emotionally charged and controversial in America. I often ponder what to do with or about them, how do we teach future generations to judge (or not) them? A middle ground of reaching some settled, wholistic understanding seems so difficult at least at this point in America’s history. I wonder if there were times when the Pyramids, the Acropolis or other ancient monuments generated the same divisiveness and controversy.

I also feel like there’s a difference between a Confederate statue out “in the wild” versus one on the battlefield where they actually fought and sacrificed. But I might be trying to rationalize.