I finally found a Confederate site that Doug wouldn’t object to visiting: the site that marks where Confederate President Jefferson Davis was captured on May 10, 1865, at the end of the Civil War.

Located in Fitzgerald, Georgia, the Jefferson Davis Memorial Historic Site houses a small museum and has a granite monument on the spot where Davis was arrested.

When I asked about the film that was supposed to be on view, I was told that the museum was no longer showing it and a new film was being developed. We were dying of curiosity as to what could be in a film they would rather stop playing at all than wait for a new film to be made, but in spite of our best sleuthing efforts, we could not find the film online. If anyone finds it, please let us know; apparently it shows up periodically.

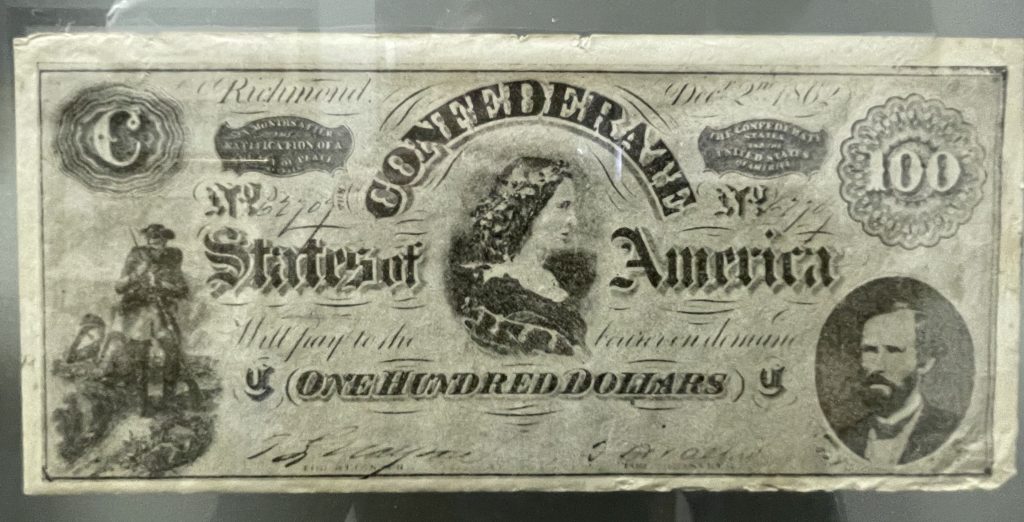

The museum is an assortment of Civil War related items and items related to Confederate President Jefferson Davis and his family. It definitely felt pro-Jefferson/pro-Lost Cause, and not the neutral site you expect a state museum to be.

Many of the exhibits were not exactly museum-caliber. See, for instance, the cover photo of True Colors: Dedicated to the Honor and Glory of our Heroic Ancestors and Proud Southern Heritage.

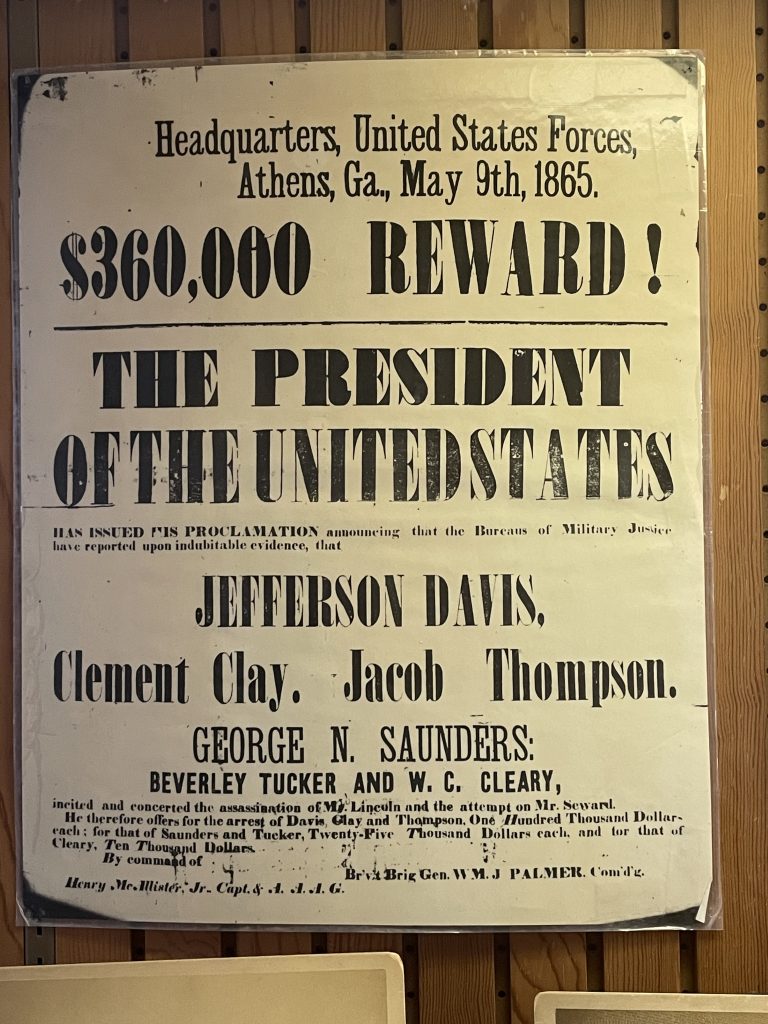

Davis fled his home in Richmond, Virginia, the White House of the Confederacy, which we had previously visited (Doug reluctantly so) on April 2, 1865. In spite of the surrender at Appomattox on April 13, Davis was still hoping the Confederacy could fight on, and was fleeing from Virginia on a quest to rally enough Southerners (from who knows where) to reverse the loss of his failed cause.

After a month on the run, Davis and his party camped for a night at this site on May 9, 1865, not realizing that Union troops were close by.

The next morning, the 1st Wisconsin Cavalry and the 4th Michigan Cavalry moved in on the small encampment and made the capture. A marker somewhat gleefully notes that the two cavalry outfits mistakenly shot at each other in the skirmish, causing two Union fatalities.

Beyond that, Davis was “taken into custody” without further incident.

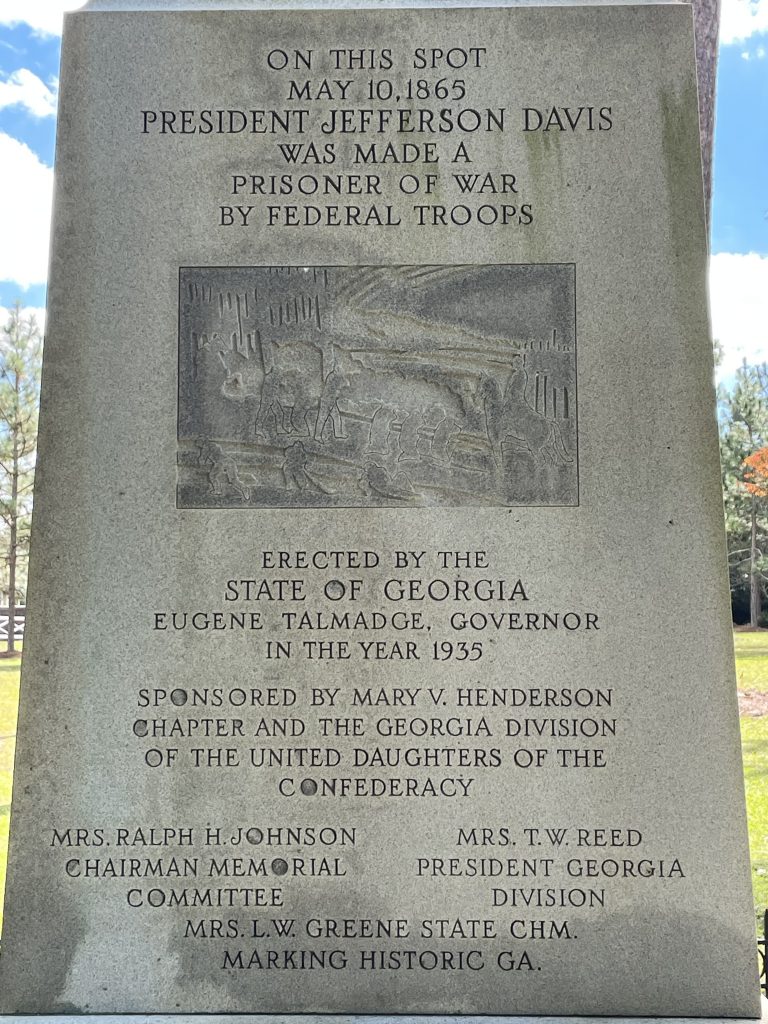

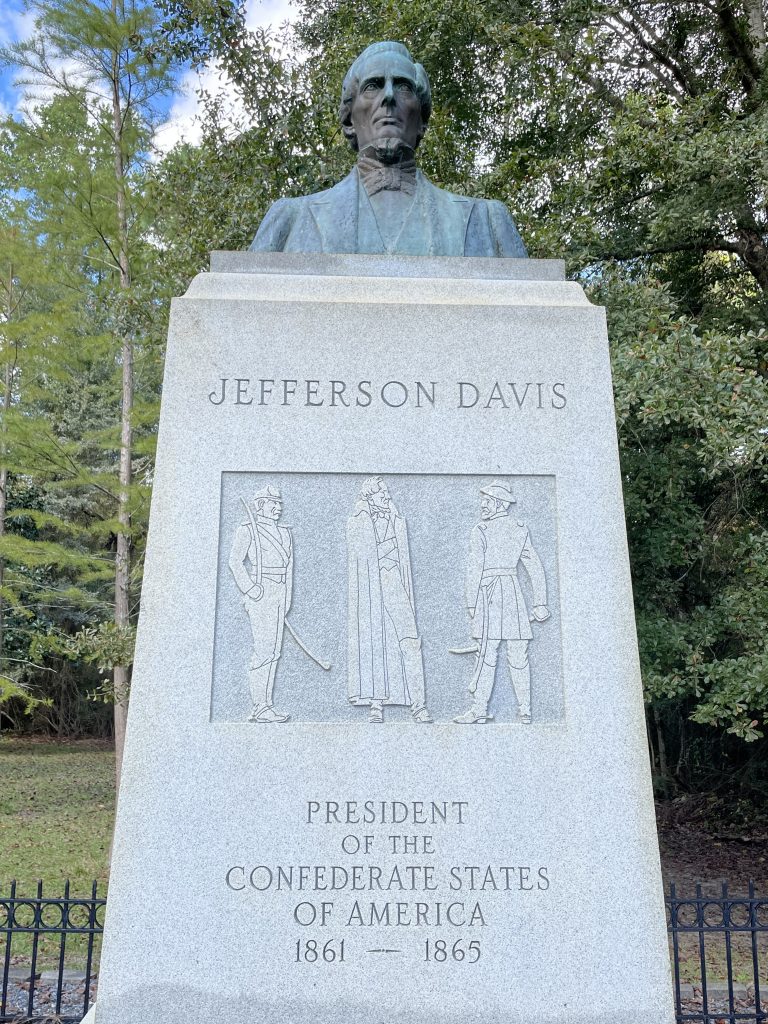

On the spot of Davis’ capture is a granite monument erected in 1835 illustrating the moment, topped with a bronze bust of the Confederate leader looking quite defiant.

On the front of the monument is an engraved scene of two Federal soldiers apprehending Davis.

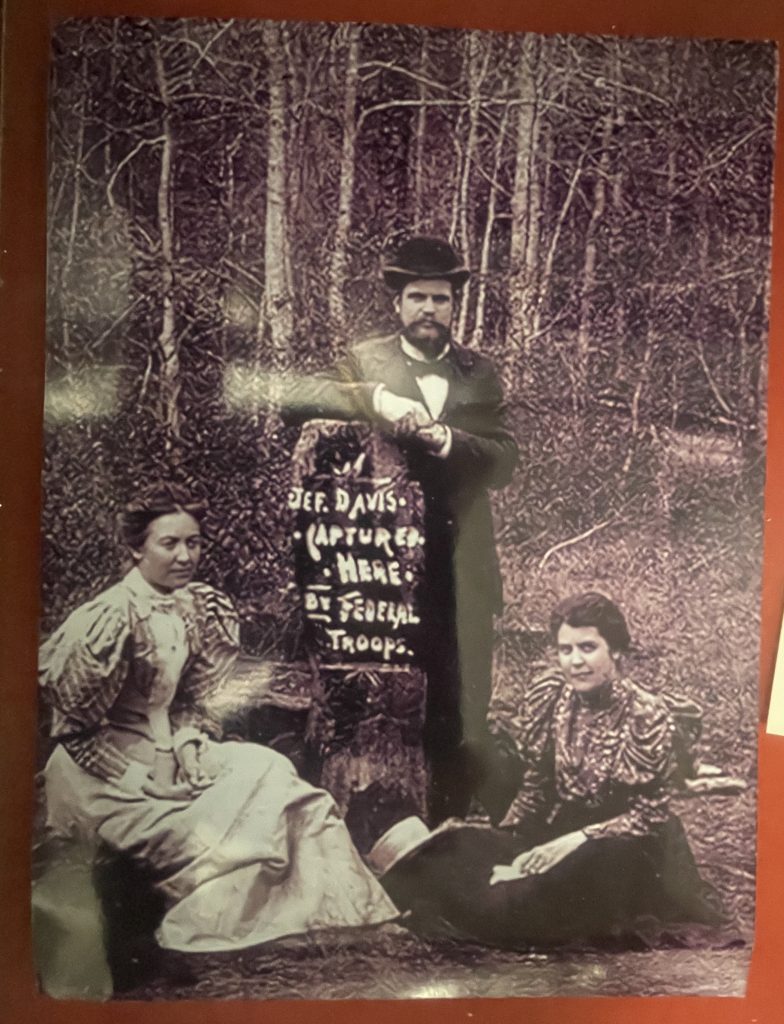

It is my opinion that Davis did not look so cocky as he is portrayed in this scene at the moment of his capture.

In addition, Davis is specifically portrayed in a long coat on this marker clearly to counter the Union-spread rumor that he was wearing a woman’s dress when he was captured — you see, it was just a big coat, not a dress!

We do tend to believe that the story of Davis in his wife’s dress was a Yankee fabrication aimed to discredit Davis, though the truth may never be known and we’re not ruling out the possibility!

The back of the granite monument on the site notes who it was erected by, and includes a few choice words about the nature of exactly what happened in this particular location.

You say “made a prisoner of war,” I say “captured.” Can you still be considered a Prisoner of War when the war is over? A document inside the museum refers to the “kidnapping” of Davis by Federal troops!

Davis was charged with treason and held for two years in a prison at Fort Monroe, Va., (in much better conditions that Union soldiers had been held at Andersonville, I must say) before finally being released without a trial.

Doug and I walked the short trail on site and had a lively debate discussion over whether Davis should have been tried for treason or released under the premise that it would help the divided nation reunite. Lincoln seemed to be on the side of offering clemency, but his assassination made it a moot point. Lincoln’s successor, Andrew Johnson (a Tennessean) granted Davis a late-term Presidential pardon.