George Washington – yes, the Founding Father, hero of the American Revolution, and first President of the United States – was a Freemason.

Lots of men of his station were Freemasons in the country’s earliest days. Washington, in fact, was the Charter Master of the Alexandria Lodge in Virginia, and still was when he stepped into the role of US President.

After Washington’s Presidency, the Lodge became a repository of artifacts related to their exalted Master. Sadly, a devastating fire in 1871 destroyed many of the items. The members of the Lodge determined that a new fireproof Lodge was desired, one that would be “a beacon that spreads the Light of Freemasonry and the legacy of Washington to all humanity.”

It took quite a while to get going, but in 1922, ground was broken on a new Lodge on Shooter’s Hill in Alexandria, Virginia.

As the plan was to build while constructions funds were being raised without the use of debt to finance the project, building lasted many years.

The massive structure was dedicated in 1932, but the George Washington Masonic National Memorial wasn’t considered complete inside and out until 1970!

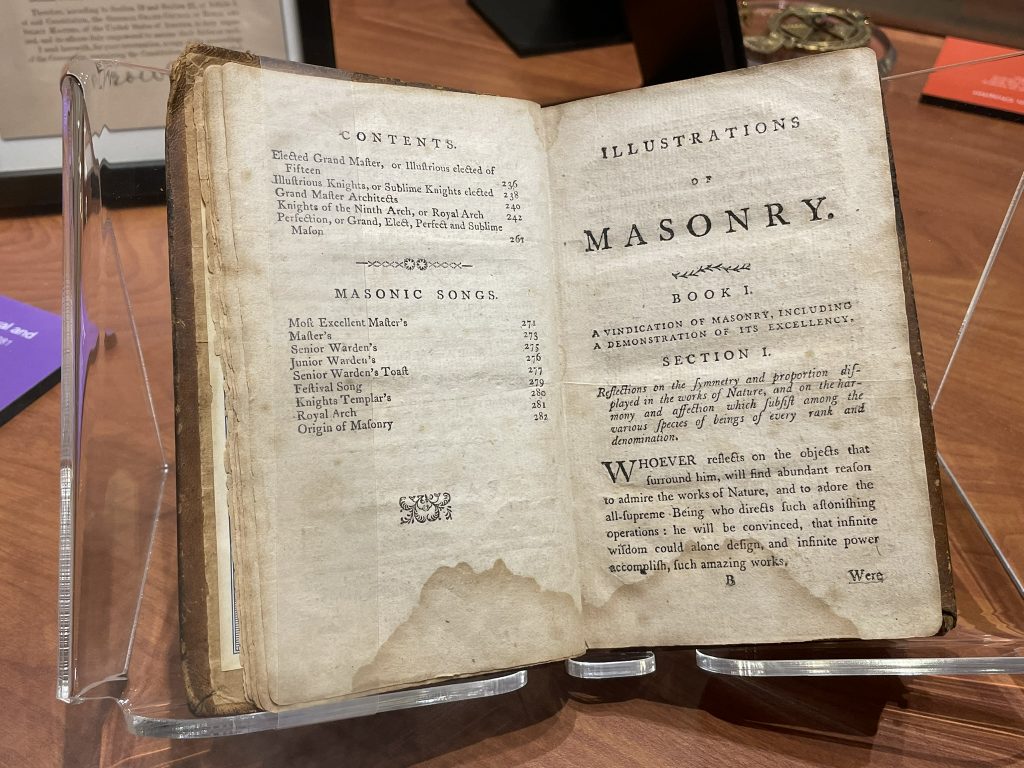

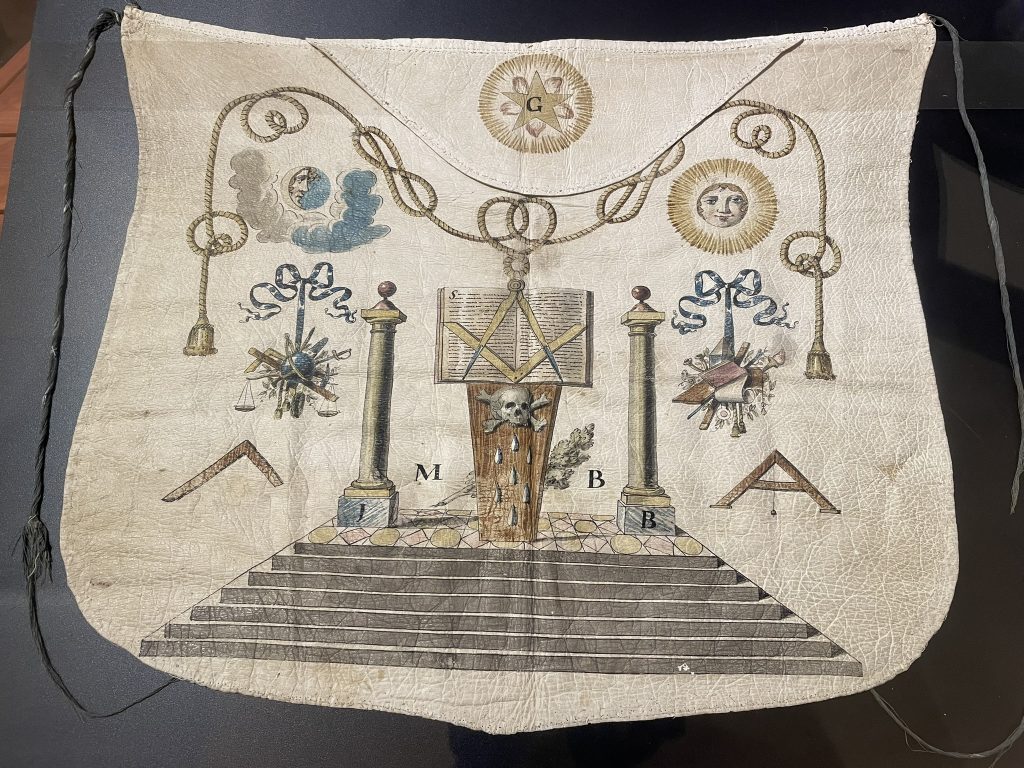

The Memorial is open to the public for tours, so we took advantage of the opportunity to check it out. They have lots of artifacts related to the history of Freemasonry in the U.S. (and worldwide) and some very special items related to Washington.

We didn’t learn much about what it means to be a Freemason on the tour, but thankfully Wikipedia knows all:

Freemasonry or Masonry refers to fraternal organisations that trace their origins to the local guilds of stonemasons that, from the end of the 14th century, regulated the qualifications of stonemasons and their interaction with authorities and clients. Modern Freemasonry broadly consists of two main recognition groups: Regular Freemasonry, which insists that a volume of scripture be open in a working lodge, that every member professes belief in a Supreme Being, that no women be admitted, and that the discussion of religion and politics do not take place within the lodge; and Continental Freemasonry, which consists of the jurisdictions that have removed some, or all, of these restrictions.

A Lodge serves as the organizational unit of Freemasonry, with local lodges serving under a Grand Lodge (i.e. at a state or border level). However, there is no international or worldwide “mother of all lodges”, so to speak; the Grand Lodges are independent of one another.

Because of this, there are lots of differences between Lodges, which can set their own rules, rituals, and procedures.

Freemason candidates ask to join (they are not invited), then must apply and be interviewed, vetted, and voted in. A Freemason advances from Entered Apprentice to Fellow of the Craft to Master Mason, learning passwords, signs and secret handshakes to signify to other members the level attained.

After the Master Mason level is attained, many members go on to receive additional degrees that vary by local offerings. Participation and activities are highly ritualized and full of symbolism, but also very secretive. Meetings have a guard to ensure privacy!

The Britannica website says Freemasons are “the largest worldwide secret society”, though honestly, if we’re talking secretive, how would anyone know?

Worldwide Freemasonry estimates range from two to six million, which is a pretty wide range, but I guess shows how secretive and disconnected it all is. There are 51 Grand Lodges in the US, with about 875,000 members.

So obviously the Freemason of today is not the stonemason of yesteryear. Why would someone want to be a Freemason today? What do they do? I found this answer on beafreemason.org:

When you become a Freemason, you begin your journey toward being a better man. You will build rich, meaningful relationships with your Brothers, commit to the service of those around you, and strive for a deeper, more honest connection with yourself and others. It’s a journey of self-discovery and enlightenment.

Oh, and the tagline to that website is “Not Just a Man. A Mason.”

And all the pictures are of smiling light-skinned men.

So of course I googled “freemasonry and women” and “freemasonry and African Americans”, and it’s not pretty. After the Civil War, black men just created their own Freemason society (Prince Hall), and it’s still in existence today.

I mean, of course the Freemasons say they are open to all, but it sure doesn’t look like it.

One thought on “The George Washington Masonic National Memorial”