Normally I’d argue that we had previously visited the American Clock & Watch Museum and we are now set for life on clock and watch museums.

However, the National Watch and Clock Museum in Columbia, Pennsylvania had a special exhibit I wanted to see something fierce: “S-Town Exquisite Clocks.”

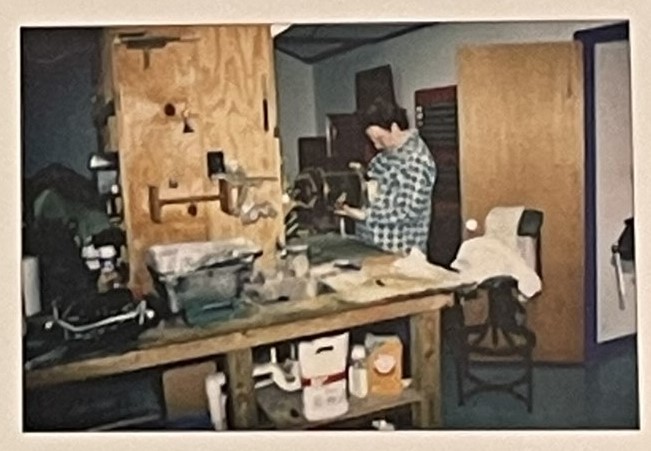

S-Town was a 2017 podcast from Serial Productions and This American Life that I absolutely loved. Every episode took radical turns, you just couldn’t see where it was going next. It focused on John B. McLemore, who was an antiquarian horologist, among other things, and I found it totally riveting. (Warning, due to language and content, the podcast is not for everyone.)

Merriam Webster defines horology as “the science of measuring time” and “the art of making instruments for indicating time.”

I really like that the definition includes the word “art” because the clocks and watches in the museum and exhibit truly are works of art.

The National Watch and Clock Museum was founded in 1977; their collection includes 12,000 timepieces, about 3,000 of which are on display.

The museum is run by the National Association of Watch & Clock Collectors, which has about 10,000 members.

As I walked through the museum, I took many pictures of all kinds of timepieces. Many were very ornate and beautiful. But, in truth, it was pretty similar to what we’ve already posted about at the American Clock & Watch Museum.

Therefore, I’ve limited all the pictures in this post to the exhibit (though the exhibit was much more than I’m showing here). It’s my own little tribute, if you will, to the amazing craftsmanship, skill, and artistry of John B. McLemore.

The clocks shown were all restored by John, though he did not own them.

I purchased the exhibit book, S-Town Exquisite Clocks (affiliate link) , at the museum, which is something I never do. It’s truly a beautiful book with exquisite photography. I enjoyed reading it and looking at the details in photographs. The notes on the pictures in this post come from the book and the labels in the exhibit.

The six clocks pictured next are Industrial Clocks, which were made to celebrate the Industrial Age; they include themes of transportation, machinery, weapons, architecture, and more. John had a lot of experience with these types of clocks, especially after a 1993 Sotheby’s auction released dozens of these clocks into the marketplace, many making their way to John for repair. The cover photo for this post is Industrial Ship’s Quarterdeck Mantel Clock, France, c 1880. Quoting from the exhibit book, “as the clock runs, the helmsman on the top rocks back and forth steering the ship’s wheel.”

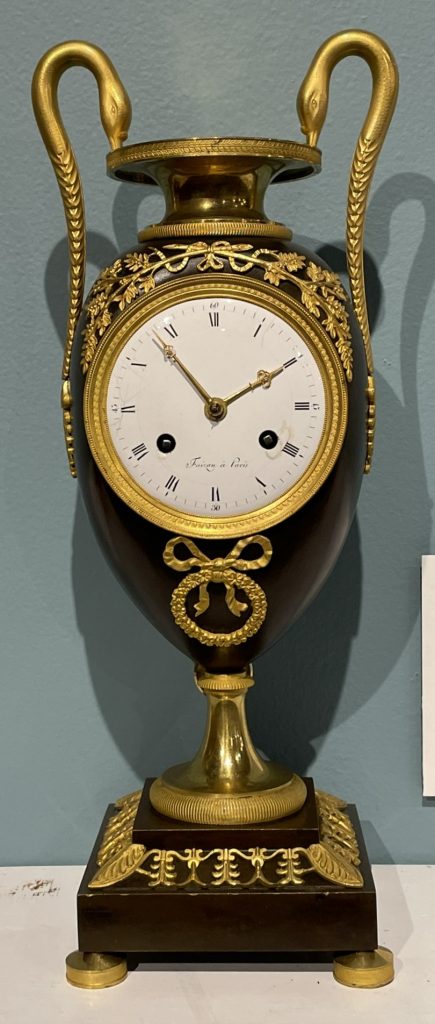

The next three clocks pictured are Empire Bronze Clocks, which are often based on Greek and Roman mythology. The gilt finish is done through a process called fire gilding, which uses mercury and is quite dangerous. John periodically used fire gilding to get his pieces as authentic as possible.

The next three pictured are Mystery clocks, which are intended to function without being clear to the viewer how it works; in regular clocks it is apparent what drives the hands and/or pendulum, but not so in mystery clocks. They majority were designed by the French. Because of their unique nature, they were often sensitive to their surroundings and required frequent attention to run smoothly. John was one of the few clock restorers who could get them running in good order again.

Very interesting!