This was our first time visiting the Outer Banks area of North Carolina – or OBX, if you’re in the know – and we liked it quite a bit, but probably because we went out of season. Most of what we wanted to do was open even though it was off-season, but parking lots were open, there were no lines at any attractions, and the traffic was a breeze. I’m not sure I’d want to drive our 24-foot-long van there during the summer time!

Jockey’s Ridge State Park in Nags Head is comprised of 427 acres, and includes the tallest living sand dune system in the eastern United States. The desert-like environment can reach 110 degrees, with the sand getting up to 30 degrees warmer!

It was our first warm day on this trip – and it was glorious! – but it was quite windy here. We saw someone trying to take off with a hang-glider, but they were not successful – I think it was a bit too windy!

The terrain was very interesting, though difficult to walk in. We both liked the patterns in the sand. The cover photo from this post is also from our stop here.

Pea Island National Wildlife Refuge is located about 10 miles south of Nags Head in OBX. We did a relatively short walk to see lots of birding activity, and I learned an important lesson related to not bringing my real camera when we go to look at birds. There were so many missed opportunities for some lovely bird portraits! The refuge focuses on providing nesting and wintering habitat for migratory birds, and is a known birding hot spot, with 370 or so species on its bird list. The refuge includes more than 5,800 of land but almost 26,000 acres of water. It was very peaceful.

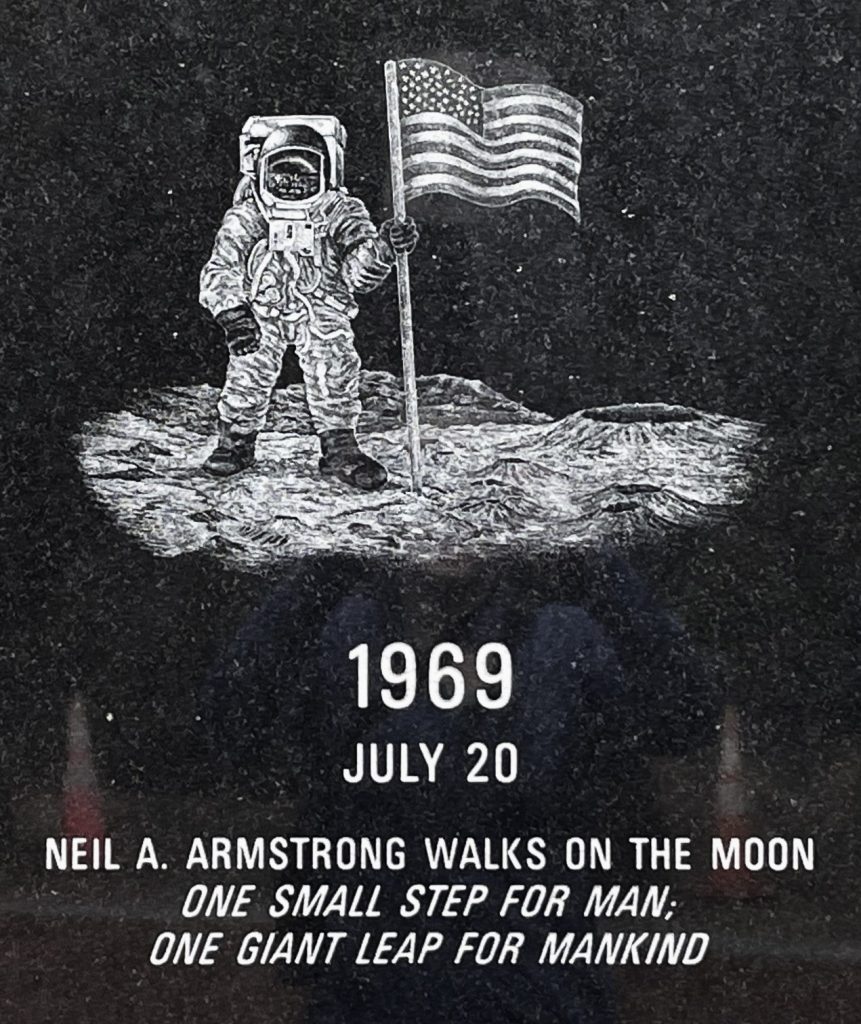

The Monument to a Century of Flight was designed and created by artist Glenn Eure and sculptors Hanna Jubran and Jodi Hollnagel Jubran. Its 14 wing-shaped pylons commemorate milestones in the first 100 years of flight. The monument is located in Kitty Hawk, a few miles from where the Wright Brothers completed the first flight.

Cayman Conch Fritters… Doug is chasing the conch fritters of his dreams. Having once had them and finding them delicious, he has been searching for a repeat performance, to no avail. But he ate all of these, all in the spirit of discovery of exploration (or so he says).

The Bodie Island Lighthouse (wherein “bodie” is pronounced “body”) is the third lighthouse in this vicinity, just south of Nags Head.

It was built in 1872 and reaches 156 feet. The light from its first-order Fresnel lens is visible for 18 nautical miles.

Clear broth style clam chowder…what is this madness? I guess to me clam chowder is New England style. This was like eating chicken noodle soup except it was “clammy.” It was good, but not exciting.

The Alligator River National Wildlife Refuge is more than 152,000 acres just over the bridge from the Outer Banks. Despite its name, we were not in expectation of seeing any alligators. Instead we were treated to lots of birds and turtles, and even got to see a family of red wolves through our binoculars (though too far for my camera). We spent a few hours starting and stopping on the Wildlife Drive. We had planned a hike, too, but spent too much time on on the drive; once it started to rain, that was the end of the hike (I did not want to risk the van on the refuge roads after getting wet!).

What happened at the Fort Raleigh National Historic Site in Manteo is endlessly fascinating, but what there is to see there is not so very exciting.

In 1585, 108 Englishmen were left at the location to establish a settlement. The next several months were rough, with low supplies and tense relations with the Native Americans. The English, suspecting the Indians were plotting to rid the island of the English, slaughtered their chief.

That first group soon returned home, but a second attempt was made in 1587, this time a true colony with women and children. For some inconceivable reason, they returned to the same island on which they had previously murdered the chief.

The situation deteriorated rapidly. Once again, the settlers ran low on supplies and saw interactions with the Indians go poorly. The group’s leader, John White, returned to England to resupply – but thanks to concerns directed elsewhere in England (with those pesky French who just wouldn’t give up their lands), it took three years for him to return. When he finally landed, the 120 or so colonists were gone. White found only the word “Croatan” carved into a post and “CRO” carved into a tree.

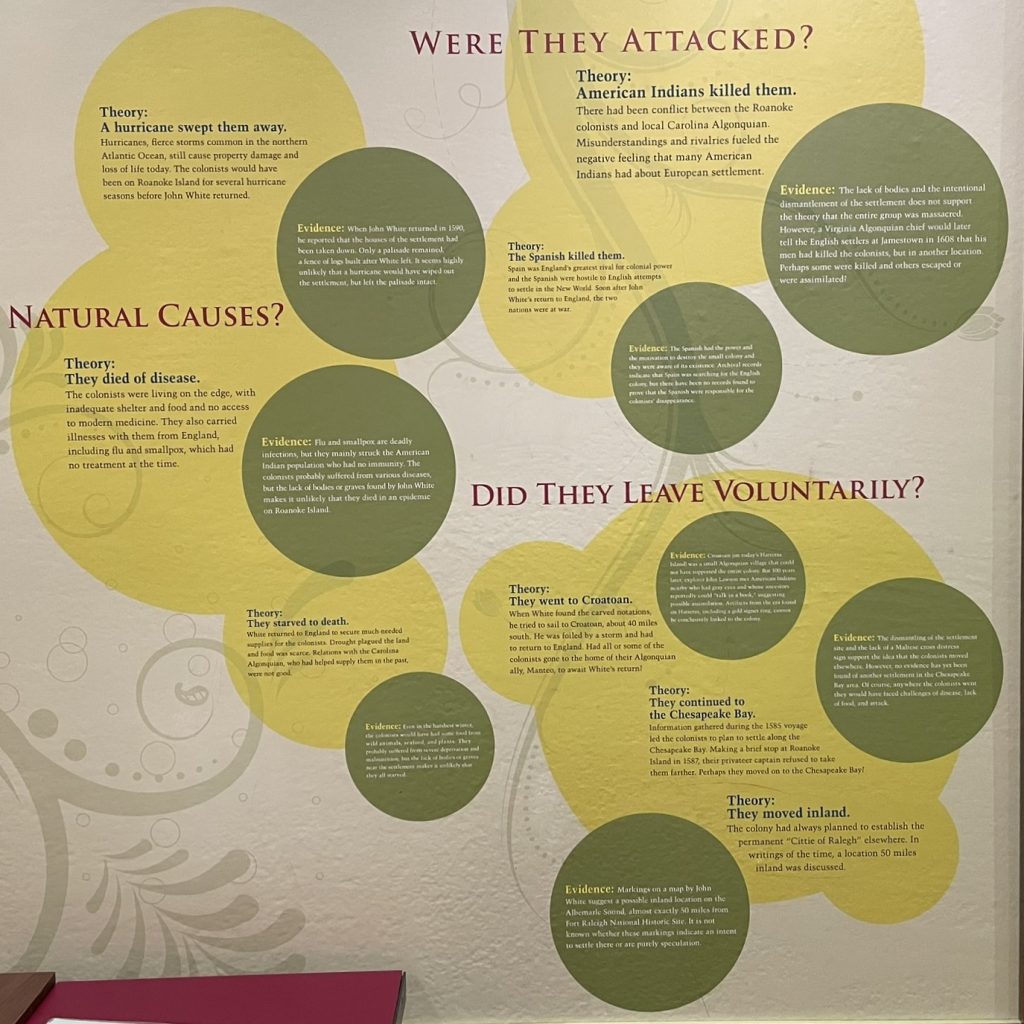

So what happened? Were they murdered by the Native Americans? Did they die of disease and/or starvation? Did they relocate to Croatan Island?

Pros and cons of each theory are all laid out in the park’s visitors center, with no firm evidence in sight.

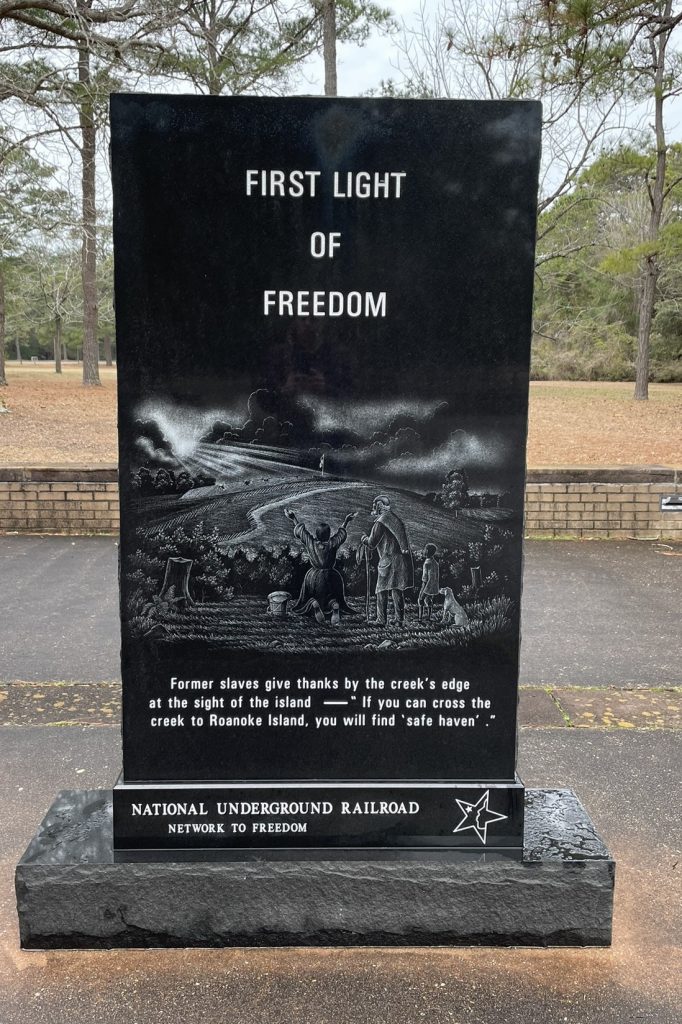

In more recent history, the location was the site of the Roanoke Island Freedmen’s Colony, an experiment conducted during the Civil war by Union Troops. When Lincoln signed the Confiscation Act, it declared enslaved people free if they made it to Union lines. Since the island was under Union control, it became a refuge for more than 3,000 people. By 1867, however, landowners reclaimed their land under the Amnesty Proclamation, and the colony disbanded.

It’s no surprise that neither of these stories have left much behind by way of things to look at. So other than read the signs, watch the movie, and walk the grounds to imagine the past, there’s not much to do at this site. Over the summer the drama The Lost Colony is performed, but of course we were there at the wrong time of the year for that.