When we set out on this trip, one of the things we’ve most been looking forward to is getting to see some of the famous sites related to the fight for Civil Rights in the United States. It’s been an education, and we’re just getting started.

Montgomery is often called the Birthplace of the Civil Rights movement, as it is home to several key moments in Civil Rights history. It is also home to some serious museums and monuments to the topic, and we did our best to give our attention to each of them. Nearly all of them prohibited pictures inside, which is just as well, as the content often felt like a crime scene where pictures were inappropriate.

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and his family resided at the parsonage for the Dexter Avenue King Memorial Baptist Church when Dr. King served there from 1954-1960. Dr. King was very active in Civil Rights issues during this time, and the parsonage was bombed while his family was home.

The tour and shop are run by individuals who had direct connections to Dr. King, and it was interesting to hear their stories while they are still able to share them personally with guests. The house has been restored to the appearance of the time the Kings lived there, including some items used by the Kings. The porch scarring from the bombing is still visible today.

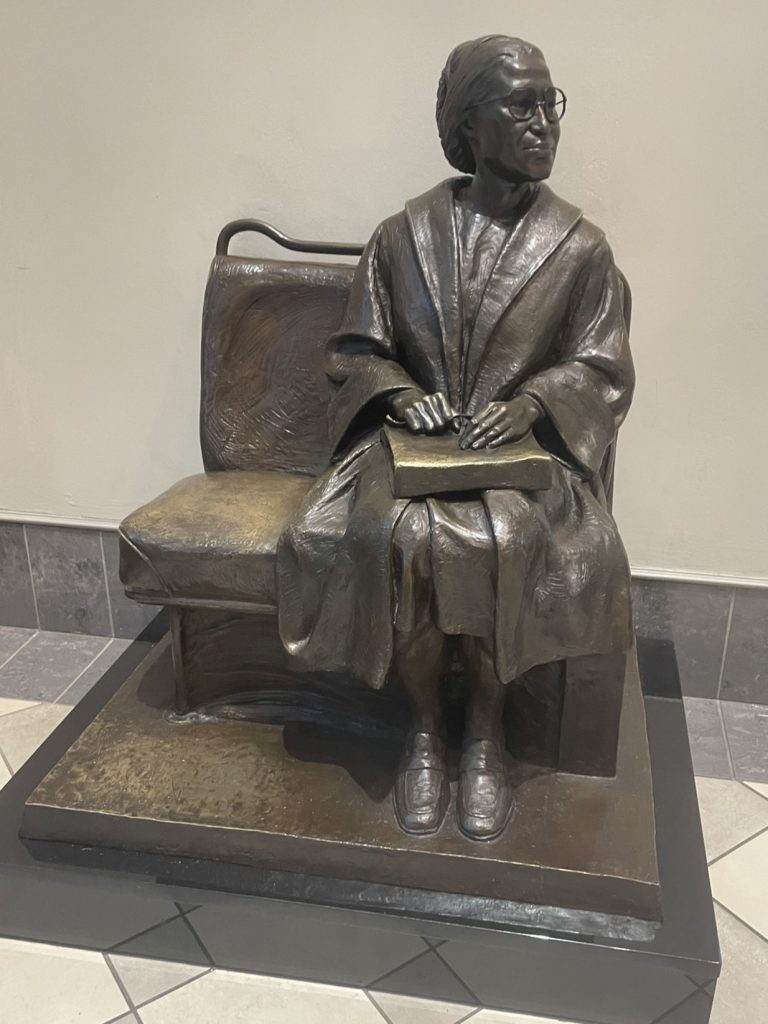

Montgomery is also the place where a tired Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat (one in which she was legally seated) for a white person in 1955. There’s a monument where she got on the bus, and a museum at the site where the arrest happened.

There are two parts to the Rosa Parks Museum experience. In the first, you get an overview of Black American Civil Rights history. The other is dedicated to the Montgomery Bus Boycott that followed the Rosa Parks arrest. The museum has a really well-done recreation of Mrs. Parks getting on the bus, the bus filling up with people, her being asked to move and refusing, and the arrest.

Following her arrest, Black Americans in Montgomery refused to ride the bus until their demands were met:

courteous treatment by bus operators; first-come, first-served seating for all, with blacks seating from the rear and whites from the front; and black bus operators on predominately black routes.

source: https://kinginstitute.stanford.edu/montgomery-bus-boycott

Did you catch that they weren’t even asking to be allowed to sit in the front?? But no, the bus company wouldn’t budge and the boycott went on for 382 days! More than a year! With 30,000 to 40,000 fares lost each day, the boycott was a severe financial blow to Montgomery City Lines, yet instead of negotiating, the city did things like banning carpooling to try to intimidate Black Americans from continuing the boycott.

In conjunction with this visit, we listened to the short autobiographical book Rosa Parks: My Story (affiliate link).

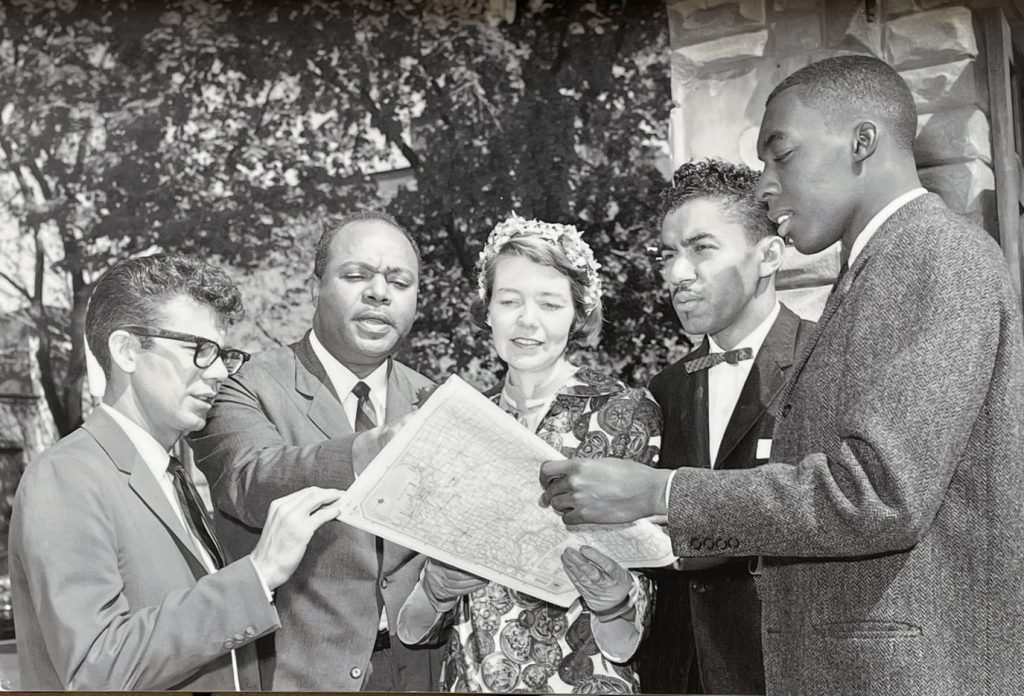

The Freedom Riders Museum honors those who worked to end segregation in bus travel in 1961. At that time, Black Americans still had to use separate waiting rooms and lunch counters, and sit in the back of the bus.

The young (none over age 22) activists – including males and females, blacks and whites – got on buses in the north where they could sit together throughout the bus, and rode the buses into the south, where segregation ruled the day.

The riders were met with extreme violence – bombings, beatings, shootings. Anniston, Birmingham, and Montgomery (all in Alabama) were the scenes of the worst incidents. In Montgomery, the activists were beaten with baseball bats and iron pipes, as were some of the reporters who were there to document the scene. Ambulances then refused to take the wounded to the hospital.

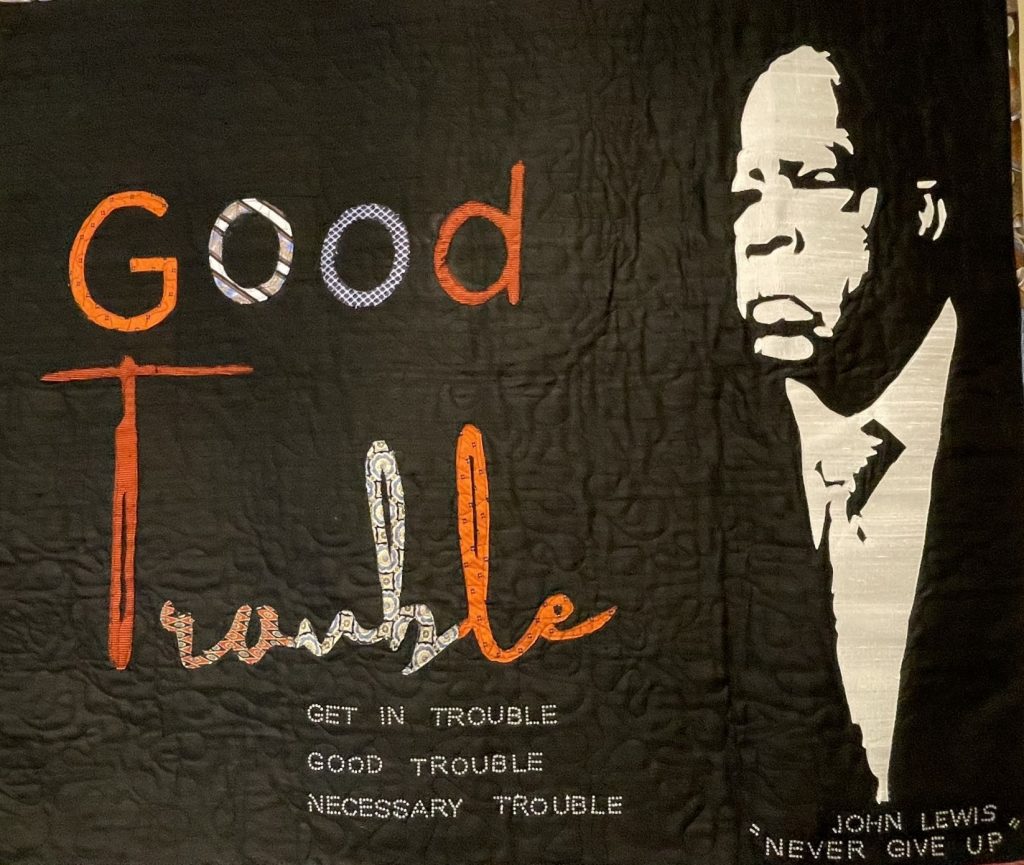

Doug and I listened to a short but interesting book, Freedom Riders (affiliate link) by Ann Bausum, which tells the story with a focus on two of the leaders, John Lewis (who went on to become a celebrated Congressman) and Jim Zwerg.

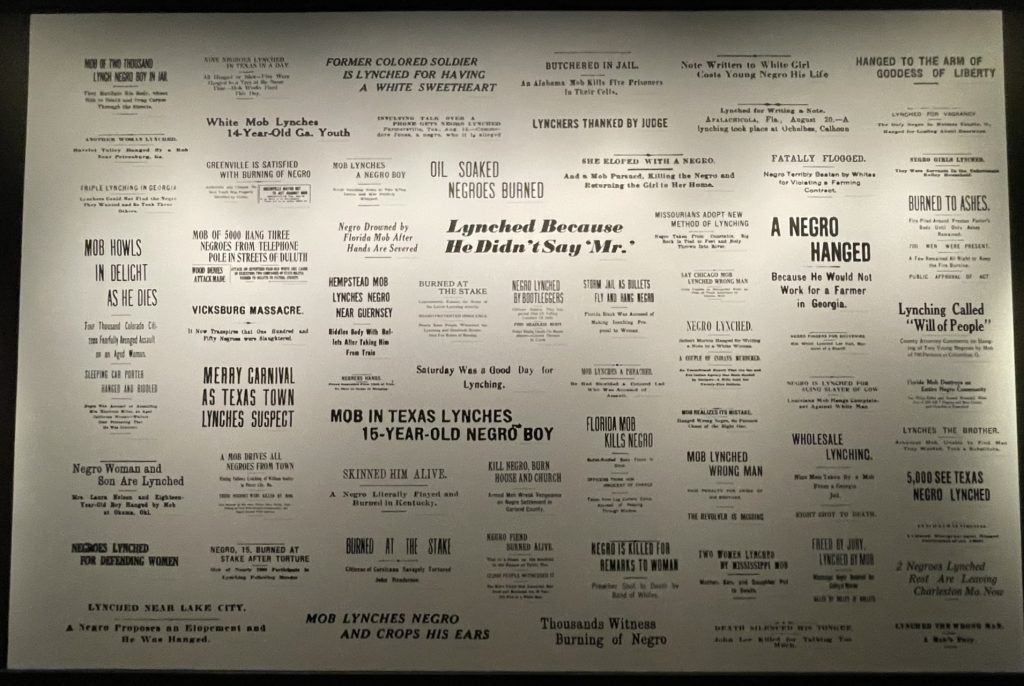

I had read to expect to spend 3-5 hours in the Legacy Museum, but thought “surely not us, we’re fast.” Well, a few hours and many tears later, we stumbled out, dazed and humbled. The museum “offers a powerful, immersive journey through America’s history of racial injustice” (per their website). It is a top-notch, spare-no-expense museum.

The outside of the museum lets you know you are going to experience African American history “from enslavement to mass incarceration.” It is the brain-child of attorney Bryan Stevenson, the author of Just Mercy (affiliate link), which we had both read several years ago (there’s also a movie, which is on our to-watch list). It’s run by Stevenson’s non-profit, The Equal Justice Initiative; after our visit, which was only $5 a person, I made a donation to the organization – the visit is that powerful.

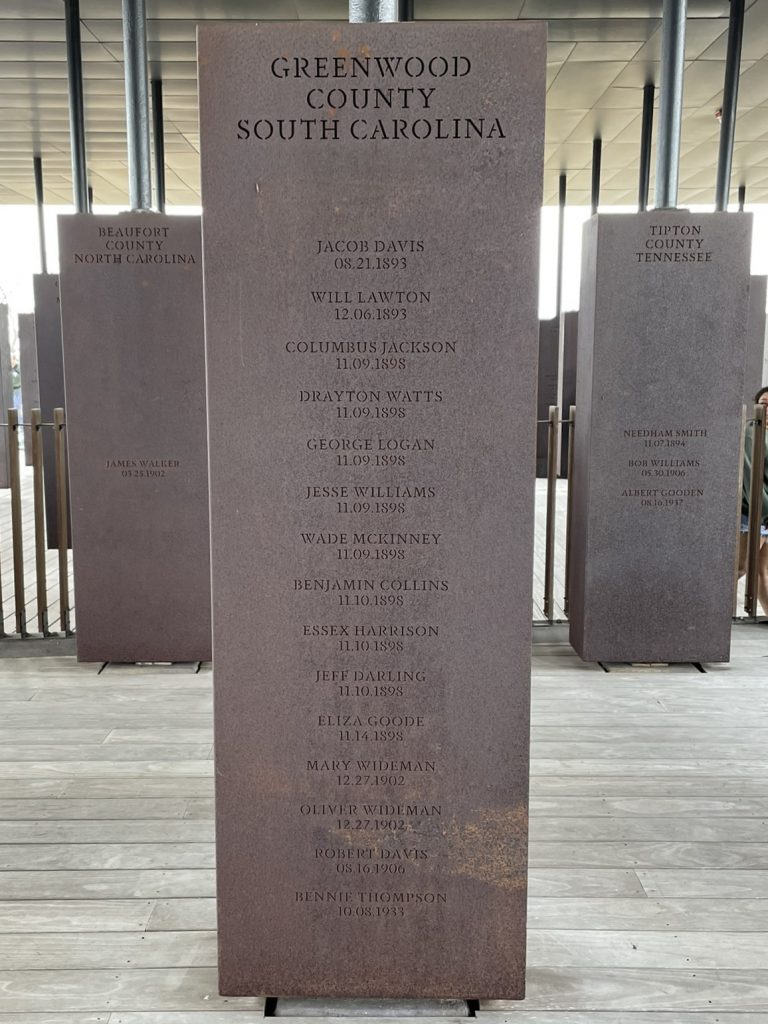

But wait, there’s more. That $5 fee to the Legacy Museum includes entrance to sister site, The National Memorial for Peace and Justice. Lest you be fooled by the name, let me clear that up for you: it’s a memorial to the “more than 4,400 Black people killed in racial terror lynchings between 1877 and 1950.”

It’s huge – overwhelmingly so – with 800 cor-ten steel monuments. At first, the monoliths are planted in the ground, then as the path gradually lowers, they rise up until they are hanging above you, reminiscent of a lynching from a tree. Each monument represents one county where a lynching took place, with the names (if known) and dates of the crime. Some counties have so many names that a smaller font had to be used.

Of course, there are surely many more lynchings that weren’t documented, so there’s a wall to remember them. Once you exit the memorial proper, the path continues through other memorials and informational sections. It’s sobering beyond description.

The museum and monument both opened in 2018. They were jam-packed while we were there. A third site is opening soon, the Freedom Monument Sculpture Park, set on 17-acres.

Our final stop was the Civil Rights Memorial, which is run by the Southern Poverty Law Center. It features a memorial outside that was designed by Maya Lin (the designer of the famous Vietnam Memorial in Washington, DC). It was inspired by a line in Dr. King’s “I Have a Dream” speech: “We will not be satisfied until justice rolls down like waters and righteousness like a mighty stream.”

The attached center is relatively small, but it’s Apathy is Not an Option movie is powerful and had both of us holding back tears (again). The Martyr Room tells the stories of the 40 people whose names are inscribed on the above-mentioned memorial. There’s also a video projection of some key moments in Civil Rights History.

Wow, what a powerful post! I’m crying just reading it, can’t imagine what you must have felt going to these sites in person. Such a sad comment on American history.

The kicker is, that’s just one city – Jackson, Memphis, Birmingham, Little Rock, etc, etc, etc all have more of the same!